In the processes aimed at the protection and enhancement of natural islands, as the construction of new islands and artificial structures in the sea waters, are fundamental the geopolitical factor, the territorial sovereignty and the norms that regulate its use and resources exploitation. Beside the preservation of marine ecosystems and environmental emergencies, the contemporary challenges are also play on the safe seas, climate risks and disasters management, communities defense and protection. In particular on these and other issues – such as the growth and dynamics of migration flows – the international community you are comparing by a number of years, involving representatives from government agencies, multilateral organizations, private sector, non-governmental organizations, research institutes, universities, community-based organizations and other stakeholders, with the aim to reduce the risks, strengthen the governance and improve the resilience in these areas.

Is crucial to identify strategies and proposals that combine resources, knowledge, specific skills and creativity to address these issues and to intervene in the territory at different scales, however the search for possible solutions, even with futuristic and utopian visions of living ways on the water and in the water, must necessarily follow common guidelines, recognized by law and shared internationally.

The geopolitical dynamics and international law

The geopolitical factor is particularly important both in terms of the protection and enhancement of natural islands, both for the construction of new artificial archipelagos. The territorial sovereignty and sea utilization are defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS): the international waters are no longer “no man’s land” but “property of all” on which is expected the Freedom of Navigation; the habitable islands can claim the 12 nautical miles of territorial waters and also benefit of the 200 nautical miles of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); for the uninhabitable islands are granted only the 12 miles and not the EEZ, then the coastal state cannot exercise the right of exclusive exploitation of natural resources; finally, regarding the “low-tide elevations” cannot claim nor the territoriality of waters and nor the EEZ.

Is probably this that has prompted an american entrepreneur, Peter Thiel, to invest 1,250,000 dollars in the design in international waters of Techtopia, a complex of islands free by laws and taxes, perhaps a utopia but certainly a paradise not only fiscal. It comes to transportable structures with a weight of 12 tons able to receive up to 270 people each, and that articulated into an integrated network will be capable of accommodate about 10 million residents by 2050; a revolutionary project also from the political point of view, created by Seasteading Institute – organization specializing in the construction of communities moving on autonomous platforms that operate in international waters – that could be realized by 2019 off the San Francisco coast.

The Spratly Islands, in the South China sea, are already a reality along one of the most vital routes for international trade, between South-East China and Indian Ocean. The archipelago (8 square kilometers, more than 750 islands, reefs, atolls), better known as the “Great Wall of Sand” and comprised between the coasts of Malaysia, Philippines and Vietnam, is also territorially disputed between Taiwan, Brunei, China and arouses many interests for several reasons: wealth of oil and gas fields, strategic location, trade routes, geopolitical factors, control of the seas, etc. On the new artificial islands – created pouring above the coral reefs just surfacing thousands of tons of sand, cement and iron – have been installed, as shown by satellite images, air and naval bases, hangars, military facilities, surveillance towers, piers, etc., which represent on the one hand an extension on open sea, on the other are based on military defense purposes. Two further artificial islands (Johnson South Reef and Gaven Reefs) are being built on vast lands reclaimed from the sea near the Spratly.

Some of Spratly Islands, the artificial archipelago created in the South China.

Differently of China, Japan has chosen to solve a legal problem with a natural solution. To preserve the Japanese territorial waters for 12 nautical miles, as well as to claim sovereignty of 200 nautical miles of the EEZ – that precludes for other nations the realization of any activities in the area (above and below the water, including the bottom) as established by UNCLOS – the region focuses on an innovative project of a large scale: the strengthening of coral reefs in the area south of the Philippine Sea, with the aim to protect the island of Okinotorishima, or at least what remains (8,000 square meters of total area, 3 platforms of reinforced concrete, 1 platform built on steel pylons of 5,000 square meters, a marine research center).

The Okinotorishima Island, in the area further south on the Philippine Sea, on which Japan has initiated some actions aimed at strengthening the coral reefs.

The maritime safety, the climate risk and disaster management, the ecosystem and community protection

One of the most recent studies in terms of safe seas and preservation of coastal ecosystems was coordinated by the Institute of International Legal Studies (Istituto di Studi Giuridici Internazionali – ISGI). The european project “Marsafenet” (2012-2016), which involved more than 80 experts in international law, has revealed some critical issues that affect:

- the preservation of marine ecosystems and environmental emergencies, problems concerning the entire planet and that until now have been entrusted to the management and policies of each State, but that would require actions at international level;

- the maritime safety threatened by widespread piracy actions, in particular in coastal areas of the “weaker countries”, which forces to intervene with local regulations and the presence of military forces on board merchant ships;

- the migratory flows, increasingly frequent and intense, and the management of illegal trafficking by criminal organizations;

- the effects produced by climate change and water level rise, that affected a gradually increasing number of islands destined to disappear and coastlines that are likely to be submerged; a situation that induces the entire international community to address the problem of ensuring to the populations affected by these phenomena, or extreme events, a place to live and where to exercise its territorial sovereignty.

In the coming decades, the effects of climate change will affect many countries overlooking the water, including in particular the South-West Indian Ocean, the Pacific Islands, the Caribbean Region and many developing countries.

Among the countries most prone to disasters in the world, Indonesia has recorded an average of 381 disaster events annually over the past five years, with more than 30,000 people directly affected. As archipelago, comprised of over 17,000 islands with more than 500 administrative districts and municipalities, the country’s geographical and political complexities represent a significant challenge to managing disaster risk.

The Pacific Islands are highly vulnerable to natural disasters and climate-related hazards. In response to requests from 15 countries, the World Bank and other partners have founded in 2007 the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative (PCRAFI) to help mitigate the fiscal risk associated with natural disasters and climate change.

In 2012, the Tropical Cyclone Evan destroyed over 600 homes and resulted the displacement of more than 7,500 people in Samoa, decimating crops and farms; the total economic damages and production losses were estimated to exceed 210 million dollars, equivalent to about 30% of the country’s GDP in 2011. The World Bank (40 million dollar financing) and other partners (additional 50 million dollars) have supported the post-disaster recovery in the islands by conducting an assessment of the socio-economic damages caused by the storm, with some recommendations for recovery and reconstruction planning.

Manono, an island of Samoa, situated in the Apolima Strait between the main islands.

In early 2014, Tonga became the first country to benefit from the initiative, obtaining more than 1,2 million dollars following Cyclone Ian. Recently Vanuatu was awarded 1,9 million dollars; in 2015, the Tropical Cyclone Pam (category 5) struck 22 of its 83 islands, causing an unprecedented destruction (188,000 people affected, 67% of population, 75,000 people left without shelter). Also the economic toll was significant, with damages and losses totaling over 449 million dollars, approximately 64% of country’s GDP.

To support the small island states in reducing climate and disaster risks – for their populations, economies and ecosystems – was launched, at the United Nations Small Island Developing States Conference in Samoa (September, 2014), the Small Island States Resilience Initiative (SISRI). Through support from a World Bank team and external experts specialized in the needs of small island states, the SISRI will help build technical and institutional capacity to manage climate and disaster risks, and for the application of innovative financial instruments that address the constraints in key of resilience. SISRI aims to support up to 24 countries in the Caribbean, Pacific and Indian Ocean during the period 2016-2018.

Also GFDRR (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery), in collaboration with governments, World Bank and different stakeholders, is working to identify and reduce the disaster risks, as well as to increase the resilience and manage the recovery after the flooding events. GFDRR – established in 2006 to support implementing the Hyogo Framework of Action (HFA) 2005-2015, a decade long plan to help make the world safer from disasters caused by natural hazards – has adopted at the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction (WCDRR), help an March 14-18, 2015 in Sendai (Japan), a new instrument, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (SFDRR). Among the priorities that will guide the actions to reduce disaster risk in the next 15 years: understanding disaster risk; strengthen governance in disaster risk management; investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience; enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response; and to “build back better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction.

This issue was discussed at the “2016 Understanding Risk Forum” that was held at the Arsenal in Venice from 16 to 20 May 2016, which was attended by representatives from government agencies, multilateral organizations, private sector, non-governmental organizations, research institutions, universities, community-based organizations, civil society, and the greater community from around the world.

During the focus, workshops, stakeholder meetings, training sessions or other activities were addressed in particular two issues: “Building a community of practice for resilience of small island states to climate and disaster risks” (World Bank Group & GFDRR) and “Dealing with coastal risks in small island states. Training session on simple assessments of coastal problems and solutions in small island developing states” (Deltares, SimpleCoast, GFDRR & World Bank Group), some questions, in particular relating to the islands, which the international community is facing in recent years.

The role which researchers and practitioners could have in the contrast to changes able to compromise in the near future the urban development and survival of the community, particularly in some geographical contexts, it has become clear in recent decades, as the importance of strategies and proposals that combine resources, knowledge, specific skills and creativity, to intervene on the territory at different scales, but following common guidelines that must be shared on an international level.

While States and experts are engaged in a confrontation right on the role that the construction of new artificial islands could have in finding solutions to some of these issues in legal terms, many professionals are involved in the research for possible solutions from the design point of view, some even proposing futuristic visions.

Overlooking the Indian Ocean and with a height above sea level of only 2 meters, the Maldives have launched long since initiatives aimed to sensitize the world on the consequences of climate change and water level rise, consequences that are also economic for a country whose development is based mainly on tourism. To ensure a possible transfer of the population and maintain at the same time the tourist activities, the new technologies could enable the realization of artificial islands, resilient to water level rise. The pilot project entrusted to the Dutch Docklands – specializing in the construction of large floating structures – involves the construction of an archipelago in proximity of the Malè atoll, where in 2004 was built the artificial island of Hulhumalé. One of the islands of the new archipelago is intended to a golf course able to attract an elite tourism and to make available, in times rather short, the funds to finance additional projects.

Some artificial islands designed by Dutch Docklands in Maldives: Royal Indian Ocean Club – golf course; Amillarah – private floating islands; Ocean Flower – waterfront villas; Greenstar – Floating hotel. (Source: Dutch Docklands Maldives, www.dutchdocklands-maldives.com)

Also the Republic of Kiribati, a small island state consisting of an archipelago located in the South Pacific to the North East of Australia, risks seeing disappear its 33 coral atolls (811 sq km, about 6 meters above sea level, 102,300 inhabitants). Mitigation actions and adaptation strategies to climate change, flooding, coastal erosion that threaten the islands may not be enough, therefore the solution considered by the government is the population transfer on artificial islands, whose construction would require substantial international aid and could be entrusted to a some companies in the United Arab Emirates, particularly expert in this field.

The archipelago of Kiribati in the South Pacific to the North East of Australia.

Not only the developing countries will be confronted with these issues to identify possible solutions in a short-term; the effects produced by climate change and sea level rise will affect many of the countries overlooking the water.

The system of dams and polders in the Netherlands, for example, will be put to the test by storms and flooding, especially along the banks of the rivers that cross the urban centers. Even in this case the expertise in hydraulic engineering, the raising of dams, the strengthening of barriers and dams, the enlargement of watercourses, and the restoration of the dunes could not be sufficient to guarantee the safety of the inhabitants, therefore are also considered some alternative and innovative solutions to the traditional ones, that have been tried and applied for centuries on these territories. It passes from the hypothesis to realize amphibious cities, where water can penetrate and drain through the urban fabric, to the idea of building raised neighborhoods in the most vulnerable areas, or “flood” houses, using water-resistant materials and floating systems. More ambitious is instead the project of Dutch planner’s Adriaan Geuze, which proposes the creation of five artificial islands, long and narrow, extended for about 30 km along the coast of Flanders and Netherlands – whose shapes and sizes will be studied in relation to different functional needs and natural factors (currents, tides, winds, etc.) – who will have the task of protecting the coasts (wave phenomena, coastal erosion, tides, etc.).

Visions and utopias to overcome future challenges

But looking at the most visionary projects, the Shimizu Corporation – company based in Tokyo – is drafting the plan for a floating city on the Pacific can accommodate the “climate refugees” and not only. Lilypad Island, designed by Vincent Callebaut like lily on the water, is a kind of self-sufficient ecopolis, able to produce their own energy by sources from solar, wind, tides, biomass, but also able to transform the CO2 present in the atmosphere, to utilize treatments for reuse the rainwater, and absorb polluting substances. An island of 500,000 square meters, floating and multifunctional (marinas, shops, residences, offices, suspended gardens, spaces for entertainment and leisure, etc.), that explores new ways of living on the water and in the water, designed for social inclusion and integration of different geographic origin populations, able to create a harmony between man and nature, while conserving biodiversity.

Lilypad Island, inspired to a lily on the water, is a kind of self-sufficient ecopolis, able to host the “climate refugees” in the world, and not only. (© Vincent Callebaut).

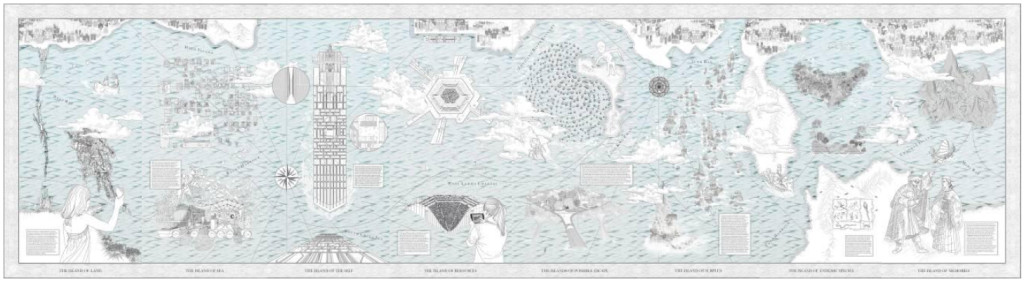

The project Hong Kong is Land, presented at the exhibition “Uneven Growth tactical urbanisms for expanding megacities” – hosted at the MOMA in New York in 2014 and edited by Pedro Gadanho – proposes the inclusion of 8 new artificial islands in the existing landscape of the city with the aim of uniting the cliffs that emerge over the sea. The design, developed by the MAP Office team in collaboration with the Network Architecture Lab Kazys Varnelis, starts from the existing scenario to get to de-contextualize and re-territorialise the area. The purpose is to give back through a specific characterization for each island (Island of Land, Island of Sea, Island of Resources, Islands of Possible Escape, Island of Surplus, Island of Self, etc.) a new identity, anyway inspired by traditional values of the Hong Kong city of and its people.

Own the most futuristic visions, if not utopian, can help to inform the debate and the international comparison on some of the challenges in the coming decades we will face, and for which will need to identify viable solutions in a short time: from the growth of the world population to limited availability of resources, from natural disasters to economic crises, from environmental problems to social integration, etc.

MAP Office contribution to “Uneven Growth tactical urbanisms for expanding megacities” exhibition at the MoMA of New York (© MAP Office team in collaboration with the Network Architecture Lab Kazys Varnelis, 2014)

In this contemporary time in which the complexity and variety of the challenges grows progressively and involves the international community, the engineering and architecture in particular, together with the other disciplines, are called to give concrete answers to the civil society, signs of creative skill and hopes for the future. Needs, awareness, opportunities, choices and achievements can lead to a result in which the project makes a difference (Alejandro Aravena, curator of the 15th International Architecture Exhibition “Reporting from the front”, La Biennale di Venezia, 28 May-27 November 2016).

Will be necessary to find solutions to the needs as desires, starting from the more physical and obvious aspects to the more intangible and to interpret, so as to contribute significantly to the life quality improvement, while respecting the individual and protecting the common good, in a perspective that allows to share knowledge, experiences and choices with the intent to imagine and design a future.

In this regard, Pedro Gadanho (curator, Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art – MoMA, New York) emphasized that “the future can no longer be what it once was” and that we can be able to imagine and design a better future; so it is important “to offer partial views of a desirable alternative universe: an urban perspective in which architects, artists and other professionals who deal with contemporary cities, attempt to combine the aesthetics of their projects with innovative solutions and social ethics of which we desperately need” (Uneven Growth tactical urbanisms for expanding megacities, 2014).

Head image: The archipelago of Kiribati in the South Pacific, to the northeast of Australia.

Arcipelaghi e isole artificiali. Dinamiche globali e sfide contemporanee

Nei processi finalizzati alla tutela e alla valorizzazione di isole naturali, come alla realizzazione di nuovi arcipelaghi e strutture artificiali nelle acque del mare, risultano fondamentali il fattore geopolitico, la sovranità territoriale e le norme che ne regolano l’utilizzo, nonché lo sfruttamento delle risorse. Accanto alla salvaguardia degli ecosistemi marini e delle emergenze ambientali, le sfide contemporanee si giocano anche sul tema della sicurezza dei mari, sulla gestione dei rischi climatici e dei disastri, sulla difesa e tutela delle comunità. In particolare su queste e su altre questioni – come ad esempio la crescita e le dinamiche dei flussi migratori – si sta confrontando da diversi anni la comunità internazionale, coinvolgendo rappresentati di agenzie governative, organizzazioni multilaterali, settore privato, enti non-governativi, istituti di ricerca, università, organizzazioni comunitarie e le diverse parti interessate, con la finalità di ridurre i rischi, rafforzare la governance e migliorare la resilienza in tali ambiti.

È fondamentale individuare strategie e proposte in grado di unire risorse, conoscenze, competenze specifiche e creatività per affrontare queste problematiche e per intervenire sul territorio alle diverse scale, ma la ricerca di possibili soluzioni, anche con visioni futuristiche e persino utopiche dei modi di vivere sull’acqua e nell’acqua, deve necessariamente seguire indirizzi comuni, riconosciuti dal diritto e condivisi a livello internazionale.

Le dinamiche geopolitiche e il diritto internazionale

Il fattore geopolitico risulta particolarmente importante sia per quanto riguarda la tutela e valorizzazione di isole naturali, sia per la realizzazione di nuovi arcipelaghi artificiali. Sovranità territoriale e utilizzo dei mari sono così definiti dalla Convenzione delle Nazioni Unite sul Diritto del Mare (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – UNCLOS): le acque internazionali non sono più “terra di nessuno” ma “proprietà di tutti” su cui è prevista la Freedom of Navigation; le isole abitabili possono reclamare le 12 miglia di acque territoriali e beneficiano inoltre di 200 miglia di Zona Esclusiva Economica (Exclusive Economic Zone – EEZ); le isole non abitabili godono esclusivamente delle 12 miglia e non della EEZ, quindi lo Stato costiero non può esercitare il diritto di sfruttamento esclusivo delle risorse naturali; infine per quanto riguarda le “low-tide elevations” (superfici affioranti) non è possibile reclamare né la territorialità delle acque né la EEZ.

È probabilmente questo ad aver spinto un imprenditore americano, Peter Thiel, ad investire 1.250.000 dollari nella progettazione in acque internazionali di Techtopia, un complesso di isole libere da legislazioni e prive di imposte, forse un’utopia ma sicuramente un paradiso non solo fiscale. Si tratta di strutture trasportabili del peso di 12 tonnellate in grado di ricevere fino a 270 persone ognuna, e che organizzate in una rete integrata potranno accogliere circa 10 milioni di residenti entro il 2050; un progetto rivoluzionario anche dal punto di vista politico, ideato dal Seasteading Institute – organizzazione specializzata nella costruzione di comunità mobili su piattaforme autonome che operano in acque internazionali – che potrebbe essere realizzato entro il 2019 al largo della costa di San Francisco.

Le Spratly Islands, sul mare della Cina Meridionale, sono invece già una realtà lungo una delle rotte più vitali del commercio internazionale, tra Sud-Est della Cina e Oceano Indiano. L’arcipelago (8 kmq, oltre 750 tra isole, scogliere, atolli), più noto come “Grande Muraglia di Sabbia” e compreso tra le coste di Malesia, Filippine e Vietnam, è conteso territorialmente anche da Taiwan, Brunei, Cina e suscita non pochi interessi per diverse ragioni: ricchezza di giacimenti petroliferi e di gas, posizione strategica, rotte commerciali, fattori geopolitici, controllo dei mari, etc. Sulle nuove isole artificiali – realizzate riversando su barriere coralline appena affioranti migliaia di tonnellate di sabbia, cemento e ferro – sono stati installati, come si evince dalle immagini satellitari, basi aeronavali, hangar, strutture militari, torri di sorveglianza, moli, etc., che rappresentano da un lato un’estensione verso il mare aperto, dall’altro rispondono a scopi militari di difesa. Altre due isole artificiali (Johnson South Reef e Gaven Reefs) sono in costruzione su vaste terre sottratte al mare in prossimità delle Spratly.

Alcune delle Spratly Islands, l’arcipelago artificiale creato nel Sud della Cina.

Diversamente dalla Cina, il Giappone ha scelto di risolvere un problema giuridico con una soluzione naturale. Per preservare le acque territoriali giapponesi per 12 miglia nautiche, nonché per rivendicare la sovranità delle 200 miglia nautiche di EEZ – che preclude ad altre nazioni di effettuare qualsiasi attività nell’area (sopra e sotto le acque, fondo incluso) come stabilito dalla UNCLOS – il Paese punta su un progetto innovativo di vasta scala: il rafforzamento della barriera corallina nella zona più a sud del Mare delle Filippine, con la finalità di proteggere l’isola di Okinotorishima, o comunque quel che ne resta (8.000 mq di superficie complessiva, 3 piattaforme in cemento armato, 1 piattaforma costruita su piloni di acciaio di 5.000 mq, un centro per la ricerca marina).

L’isola di Okinotorishima, nella zona più a sud sul Mar delle Filippine, sulla quale il Giappone ha avviato alcune azioni finalizzate al rafforzamento della barriere coralline.

La sicurezza dei mari, la gestione dei rischi climatici e dei disastri, la difesa degli ecosistemi e delle comunità

Uno degli studi più recenti in materia di sicurezza dei mari e di tutela delle coste è stato coordinato dall’Istituto di Studi Giuridici Internazionali (ISGI) del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. Il progetto europeo “Marsafenet” (2012-2016) che ha coinvolto più di 80 esperti di diritto internazionale ha messo in luce alcune criticità che interessano:

- la salvaguardia degli ecosistemi marini e le emergenze ambientali, problematiche che riguardano l’intero pianeta e che fino ad ora sono state affidate alla gestione e alle politiche di ciascun Stato, ma che richiederebbero azioni di livello internazionale;

- la sicurezza dei mari minacciata da azioni di pirateria diffuse, in particolare nelle zone costiere dei Paesi più “deboli”, che costringe ad intervenire con normative locali e con la presenza di forze militari a bordo dei mercantili;

- i flussi migratori, sempre più frequenti ed intensi, nonché la gestione di traffici illeciti da parte di organizzazioni criminali;

- gli effetti prodotti dai cambiamenti climatici e dall’innalzamento dei livelli delle acque, che interessano un numero progressivamente crescente di isole destinate a scomparire e di coste che rischiano di essere sommerse; una situazione che mette l’intera comunità internazionale di fronte al problema di garantire alle popolazioni interessate da tali fenomeni, o da eventi estremi, un luogo dove vivere e sul quale esercitare le propria sovranità territoriale.

Nei prossimi decenni gli effetti dei cambiamenti climatici interesseranno molti Paesi affacciati sull’acqua, tra questi in particolare il Sud-Ovest dell’Oceano Indiano, le Isole del Pacifico, la Regione dei Caraibi e numerosi paesi in via di sviluppo.

Tra i paesi maggiormente soggetti a catastrofi nel mondo, l’Indonesia ha registrato una media di 381 eventi disastrosi l’anno negli ultimi cinque anni con più di 30.000 persone direttamente colpite. In quanto arcipelago, composto da oltre 17.000 isole con più di 500 distretti amministrativi e comuni, le complessità geografiche e politiche dell’Indonesia rappresentano una sfida significativa per la gestione del rischio di catastrofi.

Le isole del Pacifico sono altamente vulnerabili ai disastri naturali e ai rischi legati al clima. In risposta alle richieste provenienti da 15 paesi, la Banca Mondiale ed altri partner hanno fondato nel 2007 la Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative (PCRAFI) per contribuire a mitigare il rischio finanziario associato a disastri naturali e cambiamenti climatici.

Nel 2012, il Tropical Cyclone Evan ha distrutto oltre 600 abitazioni e ha comportato lo spostamento di più di 7.500 persone nelle Samoa, decimando colture e fattorie; nel complesso i danni economici e la perdita nella produzione sono stati stimati in oltre 210 milioni di dollari, pari a circa il 30% del PIL del Paese nel 2011. La Banca Mondiale (finanziamento di 40 milioni di dollari) e altri partner (ulteriori 50 milioni di dollari) hanno sostenuto il recupero post-catastrofe nelle isole attraverso la valutazione dei danni socio-economici provocati dalla tempesta, con alcune raccomandazioni per la pianificazione del recupero e della ricostruzione.

Manono, un’isola delle Samoa, situata nello Stretto di Apolima tra le isole principali.

All’inizio del 2014, Tonga è diventato il primo paese a beneficiare dell’iniziativa, ricevendo più di 1,2 milioni di dollari a seguito del Cyclone Ian. Di recente 1,9 milioni di dollari sono stati assegnati a Vanuatu; nel 2015 il Tropical Cyclone Pam (categoria 5) ha colpito 22 delle sue 83 isole provocando effetti distruttivi senza precedenti (188.000 persone interessate, 67% della popolazione, 75.000 persone rimaste senza un riparo). Anche il bilancio economico è stato significativo, con danni e perdite per un totale di oltre 449 milioni di dollari, approssimativamente il 64% del PIL del Paese.

Per sostenere i piccoli stati insulari nella riduzione del rischio climatico e di disastro – sia per le loro popolazioni, che per le economie e gli ecosistemi – è stata lanciata, in occasione della United Nations Small Island Developing States Conference nelle Samoa (Settembre, 2014), la Small Island States Resilience Initiative (SISRI). Attraverso il supporto della World Bank e di esperti esterni specializzati nei bisogni dei piccoli stati insulari, la SISRI contribuirà a costruire capacità tecniche ed istituzionali per gestire i rischi climatici e di disastro, e per l’applicazione di strumenti finanziari innovativi che affrontino i vincoli in chiave di resilienza. La SISRI ha lo scopo di supportare fino a 24 paesi dei Caraibi, del Pacifico e dell’Oceano Indiano durante il periodo 2016-2018.

Anche GFDRR (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery), in collaborazione con i Governi, la World Bank e con le diverse parti interessate, sta lavorando per identificare e ridurre i rischi di catastrofe, così come per incrementare la resilienza e gestire il recupero dopo gli eventi alluvionali. GFDRR – creata nel 2006 per supportare l’implementazione del Hyogo Framework of Action (HFA) 2005-2015, piano decennale per contribuire a rendere il mondo più sicuro dai disastri provocati da calamità naturali – ha adottato in occasione della terza UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction (WCDRR), svoltasi dal 14 al 18 Marzo 2015 a Sendai (Giappone), un nuovo strumento, il Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (SFDRR). Tra le priorità che guideranno le azioni per la riduzione del rischio di catastrofi nei prossimi 15 anni: comprendere il rischio di disastro; rafforzare la governance nella gestione del rischio di disastro; investire nella riduzione del rischio per la resilienza; migliorare la preparazione al disastro per una risposta efficace; e “ricostruire meglio” nella fase di recupero, riabilitazione e ricostruzione.

Di questo si è discusso in occasione del “2016 Understanding Risk Forum” che si è svolto presso l’Arsenale di Venezia dal 16 al 20 Maggio 2016, e che ha visto la partecipazione di rappresentati di agenzie governative, organizzazioni multilaterali, settore privato, enti non-governativi, istituti di ricerca, università e organizzazioni comunitarie provenienti dalle diverse parti del mondo.

Nel corso di focus, workshop, riunioni delle parti interessate, corsi di formazione e altre attività sono state affrontate in particolare due tematiche “Building a community of practice for resilience of small island states to climate and disaster risks” (World Bank Group & GFDRR), e “Dealing with coastal risks in small island states. Training session on simple assessments of coastal problems and solutions in small island developing states” (Deltares, SimpleCoast, GFDRR & World Bank Group), alcune delle questioni, che riguardano in particolare le isole, sulle quali la comunità internazionale si sta confrontando negli ultimi anni.

Il ruolo che ricercatori e professionisti potrebbero avere nel contrasto a cambiamenti capaci di compromettere in un prossimo futuro lo sviluppo urbano e la sopravvivenza delle comunità, in particolare in alcuni contesti geografici, è emerso chiaramente negli ultimi decenni, come l’importanza di strategie e proposte in grado di unire risorse, conoscenze, competenze specifiche e creatività per intervenire sul territorio alle diverse scale, ma seguendo indirizzi comuni che devono essere condivisi a livello internazionale.

Mentre Stati ed esperti si stanno confrontando proprio sul ruolo che la realizzazione di nuove isole artificiali potrebbe avere nella ricerca di soluzioni ad alcune di queste problematiche sul piano giuridico, molti professionisti si cimentano con la ricerca di possibili soluzioni dal punto di vista progettuale, alcuni anche proponendo visioni futuristiche.

Affacciate sull’Oceano Indiano e con un’altezza sul livello del mare di soli 2 m, le Maldive hanno da tempo avviato iniziative volte a sensibilizzare il mondo sulle conseguenze del cambiamento climatico e dell’innalzamento delle acque, conseguenze anche di carattere economico per un paese la cui crescita è basata essenzialmente sul turismo. Per garantire un eventuale trasferimento delle popolazioni e mantenere allo stesso tempo le attività turistiche, le nuove tecnologie consentirebbero di realizzare isole artificiali resilienti all’innalzamento del livello delle acque. Il progetto-pilota affidato alla Dutch Docklands – specializzata nella realizzazione di grandi strutture galleggianti – prevede la costruzione di un arcipelago in prossimità dell’atollo di Malè, dove già nel 2004 è stata realizzata l’isola artificiale di Hulhumalé. Un’isola del nuovo arcipelago è destinata ad un campo da golf in grado di richiamare un turismo d’élite e di rendere disponibile di conseguenza, in tempi piuttosto brevi, fondi per finanziare ulteriori progetti.

Alcune isole artificiali progettate da Dutch Docklands alle Maldive: Royal Indian Ocean Club – campo da golf; Amillarah – isole private galleggianti; Ocean Flower – ville sul waterfront; Greenstar – albergo galleggiante. (Fonte: Dutch Docklands Maldives, www.dutchdocklands-maldives.com)

Anche la Repubblica di Kiribati, piccolo stato insulare composto da un arcipelago situato nel Pacifico del Sud, a Nord-Est dell’Australia, rischia di veder sparire i suoi 33 atolli corallini (811 kmq, 6 mt circa sopra il livello del mare, 102.300 abitanti). Azioni di mitigazione e strategie di adattamento a cambiamenti climatici, alle inondazioni, all’erosione costiera che minacciamo le isole potrebbero non essere sufficienti, pertanto la soluzione presa in considerazione dal governo è il trasferimento della popolazione su isole artificiali, la cui costruzione richiederebbe consistenti aiuti internazionali e potrebbe essere affidata ad alcune società degli Emirati Arabi Uniti, particolarmente esperte in questo campo.

L’arcipelago di Kiribati situato nel Pacifico del Sud a Nord-Est dell’Australia.

Non saranno solo i paesi in via di sviluppo a doversi confrontare su questi temi per individuare in tempi brevi possibili soluzioni; gli effetti prodotti dai cambiamenti climatici e l’aumento del livello del mare interesseranno molti paesi che si affacciano sull’acqua.

Il sistema delle dighe e dei polder nei Paesi Bassi, ad esempio, sarà messo a dura prova da tempeste e fenomeni alluvionali, in particolare lungo le rive dei fiumi che attraversano i centri urbani. Anche in questo caso le competenze nel campo dell’ingegneria idraulica, l’innalzamento delle dighe, il rafforzamento di sbarramenti e dighe, l’ampliamento dei letti dei corsi d’acqua e il ripristino delle dune potrebbero non essere sufficienti a garantire l’incolumità degli abitanti, pertanto vengono prese in considerazione anche soluzioni alternative e innovative rispetto a quelle tradizionali, sperimentate e applicate per secoli su questi territori. Si passa dall’ipotesi di realizzare città anfibie, dove l’acqua possa penetrare e fuoriuscire attraverso il tessuto urbano, all’idea di costruire quartieri sopraelevati nelle aree più a rischio, oppure abitazioni “inondabili”, utilizzando materiali resistenti all’acqua e sistemi galleggianti. Più ambizioso invece il progetto dell’urbanista olandese Adrian Geuze, che propone la creazione di 5 isole artificiali, lunghe e strette, estese per circa 30 km sulle coste di Fiandra e Olanda – le cui forme e dimensioni andranno studiate in rapporto alle diverse esigenze funzionali e ai fattori naturali (correnti, maree, venti, etc.) – che avranno il compito di proteggere i litorali (fenomeni ondosi, erosione costiera, maree, etc.).

Visioni e utopie per superare le sfide contemporanee

Guardando invece a progetti più visionari, la Shimizu Corporation – società con sede a Tokyo – sta elaborando il piano per una città galleggiante sul Pacifico in grado di ospitare i “profughi climatici” e non solo. Lilypad Island, disegnata da Vincent Callebaut come fosse un giglio sull’acqua, è una sorta di ecopolis autosufficiente, in grado di produrre la propria energia da fonti solari, eoliche, maree, biomasse, ma anche capace di trasformare la CO2 presente in atmosfera, di utilizzare trattamenti per il riuso delle acque piovane, e di assorbire sostanze inquinanti. Un’isola di 500.000 mq, mobile e multifunzionale (porti turistici, attività commerciali, residenze, uffici, giardini sospesi, spazi per l’intrattenimento e il tempo libero, etc.), che esplora nuovi modi di vivere sull’acqua e nell’acqua, pensata per l’inclusione sociale e per integrare popolazioni di diversa provenienza geografica, capace di creare un’armonia tra uomo e natura, tutelando la biodiversità.

Lilypad Island, ispirata ad un giglio sull’acqua, è una sorta di ecopolis autosufficiente, in grado di ospitare i “profughi climatici” del mondo (© Vincent Callebaut).

Il progetto Hong Kong is Land, presentato in occasione dell’esposizione “Uneven Growth tactical urbanisms for expanding megacities” – ospitata al MoMA di New York nel 2014 e curata da Pedro Gadanho – propone l’inserimento di 8 nuove isole artificiali nel paesaggio esistente della città con la finalità di unire le scogliere che affiorano sul mare. Il disegno, elaborato dal team MAP Office in collaborazione con il Network Architecture Lab di Kazys Varnelis, parte dallo scenario esistente per arrivare a decontestualizzare e riterritorializzare l’area. La finalità è di restituire attraverso una caratterizzazione specifica per ogni singola isola (Island of Land, Island of Sea, Island of Resources, Islands of Possible Escape, Island of Surplus, Island of Self, etc.) una nuova identità, comunque ispirata ai valori tradizionali della città di Hong Kong e dei suoi abitanti.

Proprio le visioni più futuristiche, se non utopiche, possono contribuire ad alimentare il dibattito e il confronto internazionale su alcune sfide che nei prossimi decenni ci troveremo ad affrontare, e per le quali sarà necessario in tempi breve individuare soluzioni percorribili: dalla crescita della popolazione mondiale, alla scarsa disponibilità delle risorse, dalle catastrofi naturali alle crisi economiche, dalle problematiche ambientali all’integrazione sociale, etc.

Il contributo di MAP Office per la mostra “Uneven Growth tactical urbanisms for expanding megacities” presso il MoMA di New York. (© MAP Office team in collaboration with the Network Architecture Lab Kazys Varnelis, 2014)

In questo tempo contemporaneo in cui la complessità e la varietà delle sfide cresce progressivamente e coinvolge la comunità internazionale, l’ingegneria e l’architettura in particolare, insieme alle altre discipline, sono chiamate a dare alla società civile risposte concrete, segni di capacità creativa e speranze per il futuro. Esigenze, consapevolezza, opportunità, scelte e realizzazioni possono portare ad un risultato in cui il progetto fa la differenza (Alejandro Aravena, curatore della 15. Mostra Internazionale di Architettura “Reporting from the front”, La Biennale di Venezia, 28 Maggio-27 Novembre 2016).

Occorrerà trovare delle soluzioni alle necessità come ai desideri, a partire dagli aspetti più fisici ed evidenti fino a quelli più immateriali e da interpretare, in modo da contribuire in modo significativo al miglioramento della qualità della vita, sempre rispettando l’individuo e tutelando il bene comune, in una prospettiva che consenta di condividere saperi, esperienze e scelte, con la finalità di immaginare e disegnare un futuro.

A tale proposito Pedro Gadanho (curatore, Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art – MoMA, New York) sottolinea che “il futuro non può più essere quello di una volta” e che possiamo essere in grado di immaginare e progettare un futuro migliore; è importante quindi “offrire degli scorci parziali di un universo alternativo desiderabile: una prospettiva urbana in cui architetti, artisti e altri professionisti che si occupano delle città contemporanee provano ad unire l’estetica dei loro progetti a soluzioni innovative e ad un’etica sociale di cui abbiamo estremo bisogno“ (Uneven Growth tactical urbanisms for expanding megacities, 2014).

Head image: L’arcipelago di Kiribati situato nel Pacifico del Sud, a Nord-Est dell’Australia.