Alberto Savinio was strolling down the streets of Milan, listening to the heart of one of his dearest cities [1] ; Italo Calvino, wandering about thousands of cities, was looking for their soul, powerful probe of the soul of man [2]. Cities really own a heart, and a soul; cities, also, have a flavor.

[one_third_last]

Street food in one of the commercial strip of Beijing.[/one_third_last]

[two_third]

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

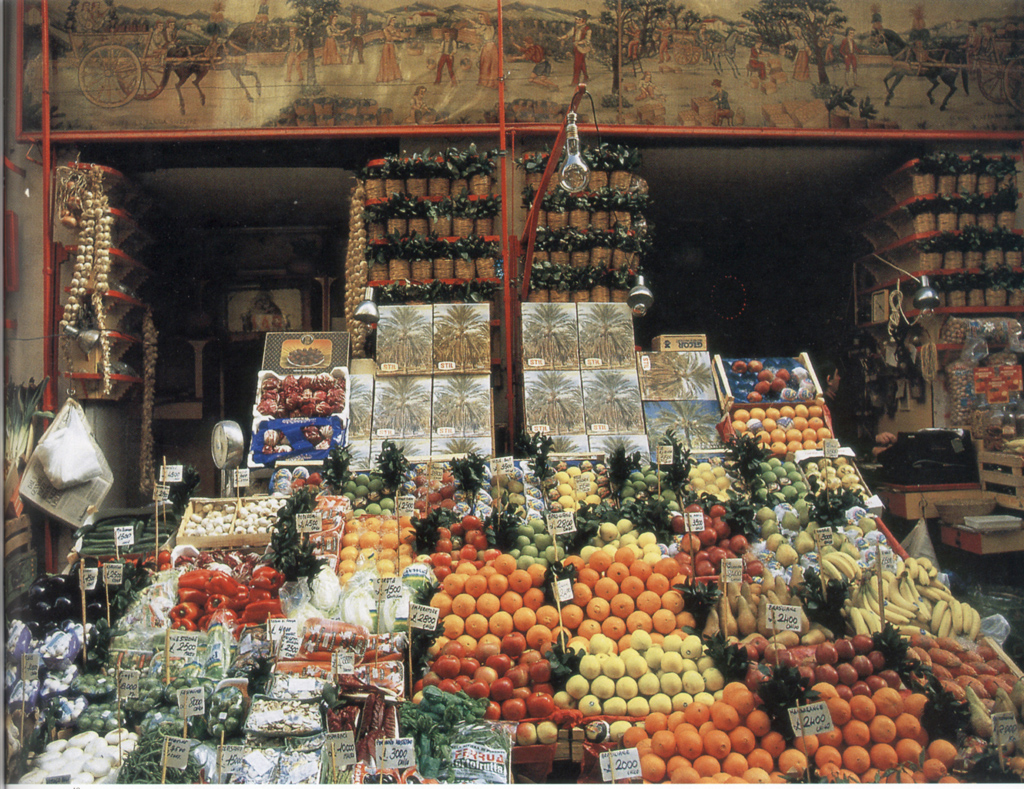

Vucciria Market in Palermo.[/one_third_last]

Every city has its own peculiar flavor, the taste of cultures and traditions that have mingled together and passed on from one generation to the next, that with time have become finer and finer or more innovative.

[two_third]

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

The Guangdong Cuisine contemplates any kind of food, any time of the day, anywhere in town.[/one_third_last]

Food tells us all about the identity of a population: food is “fruit of the earth and of man’s work”, a symbolic union between human creativity and divine gift. It is known how food is often laden with religious meanings, embodying the essence of the divine or representing sacred taboos; for Christians bread represents God’s flesh and wine is His blood; the same wine is “quarrelsome” and the liquor is “turbulent” for Muslim. The pig, for having “cloven hooves without being a ruminant”, is considered filthy by Muslims, whilst the cow is sacred to Hindus. With a joyful twist, Taoists consider eatable anything that moves, thus inviting to enjoy any fruit offered by nature: what man is left to do is inventing the best ways to cook it.

[two_third]

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

Fried cricket kebab: Cantonese proverb says “if something walks, swims or flies with its back to the sun it is edible”.[/one_third_last]

Food tells us about the relationship with environment: the ability, in the game for survival between the strongest and who is capable to adapt to any circumstance, to survive, in style, by exploiting any food resource in a clever, economic and sustainable manner. The “New Localism” or “from farm to fork”, does not represent an innovative invention of modern times, but a just a remake – in a historical moment of recession – of common habits from the ancient times.

[two_third]

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

Floating Market in Bangkok [/one_third_last]

Food tells us about the history of cities: culinary traditions sensibly vary according to the typology of a city; whether a city was the capital of a kingdom, site of a huge empire or of a lay and/or religious power. In these particular cities, alongside to very simple local cooking, “court cuisine” developed, characterized by the use of fine, rare and precious ingredients, by the sumptuousness of food presentation, by the abundance of main courses (as for example the unforgettable feast for the nomenclature of Pope Clemente VI set by the Palais des Papes in Avignon and counting 118 beefs, 1.033 roasted sheep, 1.195 geese, 7.428 chickens, 50.000 cakes, 39.980 eggs and 95.000 different types of bread). The majesty of court cuisine has influenced, in turn, popular cuisine that, starting from humble and easy-to-fetch local ingredients, has proven to be very ingenious in the creation of the finest works of culinary art (the very famous Sicilian cassata is one of the first examples).

Food tells us about the relationship between city and territory: in continental cities there are culinary traditions made up of just a few courses, characterized by robust recipes and strong flavors, whilst in coast cities thousands of recipes and distinct flavors can be listed, more delicate, sweeter and spicier, sincere or elaborated to “deceive” the palate. This difference is not solely due to the availability of seafood, but more importantly to the nature of seaside towns. The cities have been built as fortress and, only later on, they became a harbor for goods exchange: Port Cities, par excellence, emphasize this function.

[two_third]

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

Fish Market in Shanghai.[/one_third_last]

Port Cities are the gateways for the transit of people and goods where, like a bag of flour not properly sealed, something is shed on the ground during goods loading. The cooking of Port Cities is rich in spices, in transit (and gone lost) from the East; Port City cooking uses ingredients, seasonings and preparations that recur in an extraordinarily similar way from port to port of the most distant cities of the world; Port City cooking is made up by a mixture of traditions that are interlaced together so tightly they lose their own identity, like a mix of different flours.

[two_third]

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

Spice shop in the Grand Bazaar of Istanbul.[/one_third_last]

It is not by accident that Port Cities show off the richest and most imaginative gastronomic traditions of the world: cooking nourishes itself with the knowledge and the exchange of primary goods and traditions. Shanghai, for instance, is one of the three biggest and most active Port Cities in the world and does not just have one traditional cooking but it has two: Benbang cooking and Haipai cooking are a collection and a reinterpretation of the best ancient culinary traditions passed on by the Eight Schools of the Middle Kingdom.

WaterFood is a column centered on the culture of food dedicated to Port Cities due to the extraordinary richness and beauty of their ‘karstic’ interconnection with cooking; the articles of WaterFood will propose the bliss of the discovery of the beating heart and of the most sincere soul of Port Cities by tasting their flavor, by making the city a living cook book.

Some may read the future by looking at the patterns formed by the tealeaves sitting at the bottom of a cup. WaterFood will try to read the story, traditions and identities of Port Cities by looking at a plate.

[two_third]

[/two_third]

[one_third_last]

Eating deep-fried scorpions is a delicacy of Shandong cuisine, also very popular in Beijing and Shanghai.[/one_third_last]

[1] Alberto Savinio, Ascolto il tuo cuore, città, 1944.

[2] Italo Calvino, Le città invisibili, 1972.

Il Gusto delle Città Portuali. Il Cibo e la Città

Alberto Savinio attraversava Milano ascoltando il cuore di una delle sue più care città [1]; Italo Calvino, attraversandone mille, cercava l’anima delle città, potente scandaglio di quella umana [2]. Le città hanno davvero un cuore, e un’anima; le città hanno, anche, un sapore.

Ogni città ha un suo sapore particolare, il gusto di culture e tradizioni che si sono intrecciate e tramandate di generazione in generazione, che si sono andate affinando o innovando nel corso della loro storia.

Il cibo racconta l’identità di un popolo: è il “frutto della terra e del lavoro dell’uomo”, simbolica unione tra creatività umana e donazione divina. È noto come spesso il cibo sia carico di significati religiosi, incarnando l’essenza stessa del divino o rappresentando tabù inviolabili; per i cristiani il pane è la carne di Dio e il vino il sangue; lo stesso vino è “rissoso” e il liquore “tumultuoso” per i musulmani. Il maiale, l’unico animale che ha “l’unghia bipartita ma non rumina”, è considerato da questi ultimi immondo, mentre la vacca è sacra per gli indù. Con una gioia tutta particolare, invece, i seguaci del Tao considerano commestibile tutto ciò che si muove, invitando a godere di qualsiasi frutto offerto dalla natura: sta all’uomo inventare i modi migliori per cucinarlo.

Il cibo racconta il rapporto con l’ambiente: l‘abilità, nel gioco della sopravvivenza tra chi è più forte e chi riesce ad adattarsi, a sopravvivere con stile attraverso l’utilizzo sapiente, economo e sostenibile delle risorse alimentari. La “cucina di territorio”, o a “Km zero”, non è un’invenzione contemporanea, ma una rivisitazione – in un frangente di recessione – di pratiche ordinarie nell’antichità.

Il cibo racconta la storia delle città: le tradizioni culinarie variano sensibilmente se una città è stata capitale di un regno, sede di un impero o centro di un potere laico e/o religioso. In queste particolari città si è sviluppata, accanto alla più modesta cucina di territorio, una “cucina di corte” caratterizzata dall’utilizzo di ingredienti sofisticati, rari e preziosi, dalla sontuosità delle presentazioni, dall’abbondanza delle portate (indimenticabile rimane il banchetto per la nomina di Papa Clemente VI allestito nel Palais des Papes ad Avignone con i suoi 118 buoi, 1.033 pecore allo spiedo, 1.195 oche, 7.428 polli, 50.000 torte, 39.980 uova e 95.000 forme di pane). La grandiosità della cucina di corte ha, a sua volta, modificato la cucina popolare che, a partire da ingredienti umili e facilmente reperibili sul territorio, ha dato prova di grande ingegno nella creazione di raffinate opere d’arte culinaria (la tanto celebrata cassata siciliana ne è uno dei primi corollari).

Il cibo racconta il rapporto tra città e territorio: si trovano tradizioni culinarie fatte di pochi piatti con ricette robuste e sapori forti nelle città continentali, mentre nelle città costiere si contano migliaia di ricette e sapori differenziati, più delicati, dolci e speziati, sinceri ma più spesso immaginati per “truffare” il palato. Questa differenza non è soltanto dovuta alla disponibilità dei prodotti ittici, quanto alla natura stessa delle città di mare. Le città originariamente sono state costruite a scopo difensivo e, in seguito, al fine di incontrarsi per scambiare merci: le città portuali, per eccellenza, enfatizzano questa funzione.

Le città portuali si comportano come gateway di transito di persone e merci dove, come in un sacco di farina chiuso male, qualcosa si disperde al suolo durante le operazioni di imbarco. La cucina delle città portuali è ricca di spezie, in transito (e perse) dall’Oriente; utilizza ingredienti, condimenti e preparazioni che ricorrono in modo straordinariamente similare nei porti delle più lontane regioni del mondo; presenta commistioni di tradizioni i cui caratteri non sono più distinguibili come in una miscela di polveri diverse.

Non a caso le città portuali vantano le tradizioni culinarie più ricche e fantasiose del mondo: la cucina si alimenta della conoscenza e dello scambio, sia di materie prime che di tradizioni. Shanghai ad esempio, una delle tre città portuali più grandi e attive del mondo, non ha una cucina tradizionale, ma ne ha due: cucina Benbang e cucina Haipai raccolgono e reinterpretano il meglio delle millenarie tradizioni culinarie tramandate dalle Otto Scuole dell’Impero di Mezzo.

WaterFood è una rubrica di cultura del cibo dedicata alle città portuali per la straordinaria ricchezza e bellezza dei loro nessi carsici con la cucina; gli articoli proporranno il piacere della scoperta del cuore pulsante e dell’anima più sincera delle città assaggiandone il sapore, facendo diventare la città un libro di cucina vivente.

Alcuni riescono a leggere i destini futuri nella disposizione delle foglie sul fondo di una tazza di tè. WaterFood cercherà di leggere la storia, le tradizioni, le identità delle città portuali guardando dentro il piatto.

[1] Alberto Savinio, Ascolto il tuo cuore, città, 1944.

[2] Italo Calvino, Le città invisibili, 1972.