Cities and landscapes around the world are the result of many centuries of human interventions. They are a spatial palimpsest of events and processes that have modified the formation of landscapes and cities and, in some cases, even erased what others had previously done (Corboz, 1998). The insertion of spaces of oil into the existing territory used existing patterns and created new ones, giving rise to a palimpsestic global petroleumscape that links production and management of industrial flows through a particular configuration of space (C. Hein, 2013, 2018). Throughout the twentieth century, as oil became a key player in the transformation of space, it helped the emergence of diverse spaces, ranging from industrial sites to headquarters and cultural facilities. In the network of oil spaces, port cities have taken on a particular role. The petroleum industry used the ports to access the hinterland. They built oil related structures, such as oil tanks, pipelines and industrial and sometimes administrative buildings nearby, often in the vicinity of dense urban environments (C. Hein, 2013). These landscapes are characterized by fragmentation, a term proposed by the urbanist Bernardo Secchi (B. Secchi, 2000) to describe a spatial condition that belongs to the contemporary cities. Here, left-over of contaminated industrial landscapes form a set of fragments with a high potential for change. In this situation, utopian scenarios designed to present possibilities of change can help envisioning a reality better than the current one (B. Secchi & Viganò, 2009).

Previous design experiences have been carried out for the cities of Rotterdam and Dunkirk (C. Hein, 2017, 2019; C. Hein & De Martino, 2018). In 2018, the studio built upon an ongoing collaboration with Michelangelo Russo from the Department of Architecture of Federico II in Naples. The students from TU Delft took their analysis notably to the eastern part of Naples. Historical choices, urban activities and socio-economic relationships characterize a strategic area in Eastern Naples, where the city becomes landscape (Russo, 2014, 2016). In this area, the port faces a problem of relationship with the city, resulting in discontinuity and fragmentation for the waterfront areas. East Naples, and specifically the area of oil storage of Q8 called “Ambito 13”, is a critical area as it covers a huge space in between the city and the peripheral residential areas of Ponticelli and Barra (previous image).

The oil refinery and oil tanks in this area separate the city center from the rest of the Eastern city. Here, commercial and oil flows intertwine with heavily urbanized areas. However, this mosaic of different landscapes and relations also has great potentiality for redevelopment (next image). Both the Naples Municipality and the Central Tyrrhenian Sea Port System [1] are vying for this site. Their competing interests present an opportunity to rethink the port-city relationship, to redevelop the abandoned oil-related industrial areas, and to re-launch East Naples as a new place for urban living. The studio therefore asked the following question: How can port and city use the container port extension – beyond the presence of the oil sites – as an opportunity for an era beyond oil?

Naples in a Satellite view. In yellow the areas related to oil.

Naples in an oil perspective

The Naples oil story reflects global developments in other ports where spatial transformation has gone hand in hand with growing throughput of oil flows in the last 100 years. At the beginning of the 20th century, the national government opted to transform Naples into one of the most important Italian oil cities, making use notably of colonial ties to Africa and specifically Libya. From 1920s on, East Naples, located at the edge of the city, assumed the character of an industrial periphery. In the 1930s, Naples had the largest and most important national refinery system and until the 1960s the port played an important role as national oil port. The result was the creation of miles of roads and pipelines near urban neighbourhoods. The strategic position of this portion of territory has been recognised by the national government, which in 1998 declared East Naples a site of national interest (SIN). Since then, national and local authorities have introduced multiple plans to redefine a future for this area. Both the city plan (2004) and the city implementation plan (2009) describe the port infrastructure as a physical barrier between the city and the sea (Comune di Napoli, 2004, 2009). But, so far, no concrete actions have been taken.

A large part of the territory of East Naples is occupied by oil facilities (120 ha). The rest, around 300 hectares includes industrial plants of variable dimensions. Some of these facilities are still active, some others partly disused or abandoned. In its municipal and implementation plans, the Naples city government proposed the relocation of all the oil plants, as well as the conversion in new productive sites of the disused industrial facilities. The plans included the urban reorganization of the area, and more generally the territorial regeneration of the eastern landscape through the construction of a large park. According to the city vision, East Naples can take on a strategic role. It can serve as hinge between the historic city, the regional hinterland and the cities along the Vesuvian and Sorrento coasts. The official plans, therefore, proposed to re-launch this area as a place of living, to enhance the landscape, to regenerate the abandoned industrial heritage, to create new manufacturing, commercial and tourist attractions. This transformation depends on the removal of oil from the city and from the port, including the pipelines. The removal is needed to guarantee a safe and a good living environment (Comune di Napoli, 2004). The municipality therefore proposed the construction of an offshore oil tanker plant beyond the Gulf of Naples, connected by subsea pipelines to a land area destined for storage.

In 2006, the Campania Region, the Naples City Council, the “Società Napoli Orientale S.c.p”., Kuwait Petroleum Italia S.p.A., Kuwait Refining and Chemistry S.p.A., signed a memorandum of understanding for the transformation of the Q8 Area. This was also the first step towards the definition of a specific plan of intervention, the Pua for Ambito 13 [2]. The area of interest “Ambito 13 ex-refineries” contains the oil tanks which belong to the oil companies Q8, Esso, and Agip. The Pua was approved in 2009 and it aimed, amongst other interventions, at the relocation of the oil facilities, the realization of the urban park and the restoration of the main water lines and the creation of new productive settlements. For the management of this program, the City Council proposed another agency, the “Società Napoli Orientale”, which has been entrusted with promoting the regeneration and development of the eastern part of the city [3]. The company Napoli Orientale in collaboration with the municipality has asked the Neapolitan urbanist Carlo Gasparrini to make a proposal. He proposed the gradual re-naturalisation of the oilfield as park to facilitate the integration between Naples and its eastern part (Russo, 2012) (next image).

This vision of a strong connection of city and coastline, as proposed by the municipality, is in contrast to the scenario of the Central Tyrrhenian Sea Port System. Since 2011, the Port Authority has been planning to extend the container terminal into the eastern area of the port (Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mar Tirreno Centrale, 2017). The city plan asks for a relocation of all oil facilities outside the city. However, the oil companies such as Q8 have concessions until 2027 to use the port and the land in East Naples for storage of oil. Therefore, oil facilities can not be relocated until real alternatives will be provided.

This duality of visions has already lasted for many years, creating uncertainty and institutional conflicts today. The regeneration of East Naples can only take place within a strategic and metropolitan vision that looks at the port as a strategic engine for the territory and to East Naples as a place to live (Castigliano, De Martino, & Russo, 2018; De Martino, 2016). Design projects can help comprehensively rethink the site.

Proposal by the Studio Carlo Gasparrini.

Utopian design proposals

Rethinking Naples in the era beyond oil requires building upon the history and reimagining the space in a creative and provocative way. It requires rethinking the role of the port with a stronger relation to the city and the landscape. Marijn Heijnis and Wei-Chieh Wang, two students from the MSc 2 studio “Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil” TU Delft have adapted this strategy. They have investigated the port infrastructure, its scale and impact. Based on their carefully study of the site they have suggested the integration between port activities and urban forms.

Marijn Heijnis’ project the “Mercati Napoletani” aims to re-establish a sense of belonging between the community of San Giovanni a Teduccio (behind the port) and the port. He proposes the concept of the market as a place where people living in San Giovanni can develop harbour-related businesses and connect to outsiders and tourists. Marijn suggests that new creative activities and industries 4.0 – in the field of smart production, smart energy and port related services – will replace the heavy oil industry and infrastructures. According to his proposal, traditional urban relations, the way of living in the city, historic materials and rituals (Image a) can become a source of inspiration to rethink the port-city of Naples in an era beyond oil. The enormous areas used for oil production and some areas used for containers will become vacant. Therefore, Marijn proposes to reuse the old oil tanks both on the dock and in the industrial area as laboratories of innovation in which start up and creative businesses can establish their activities and work in symbiosis with the port (Image b). Inside the tanks, he projects some typical architectural typologies of Naples, such as arches, colonnade, or the balcony (Image c). These elements are meant to coexist with colourful containers creating a fusion between past, present, and future. In this long term scenario, the containers lose their original function and are reused as housing on top of existing buildings. According to the project, in the future the port will create room for the city allowing new lifestyles and clean industries to merge with existing port activities. The volcano serves as background to this vision that reinvents the port-city relationship through an integration between the port landscape and the urban community.

a_Spatial qualities. (Marijn Heijnis, MSc 2 Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil, Fall 2018)

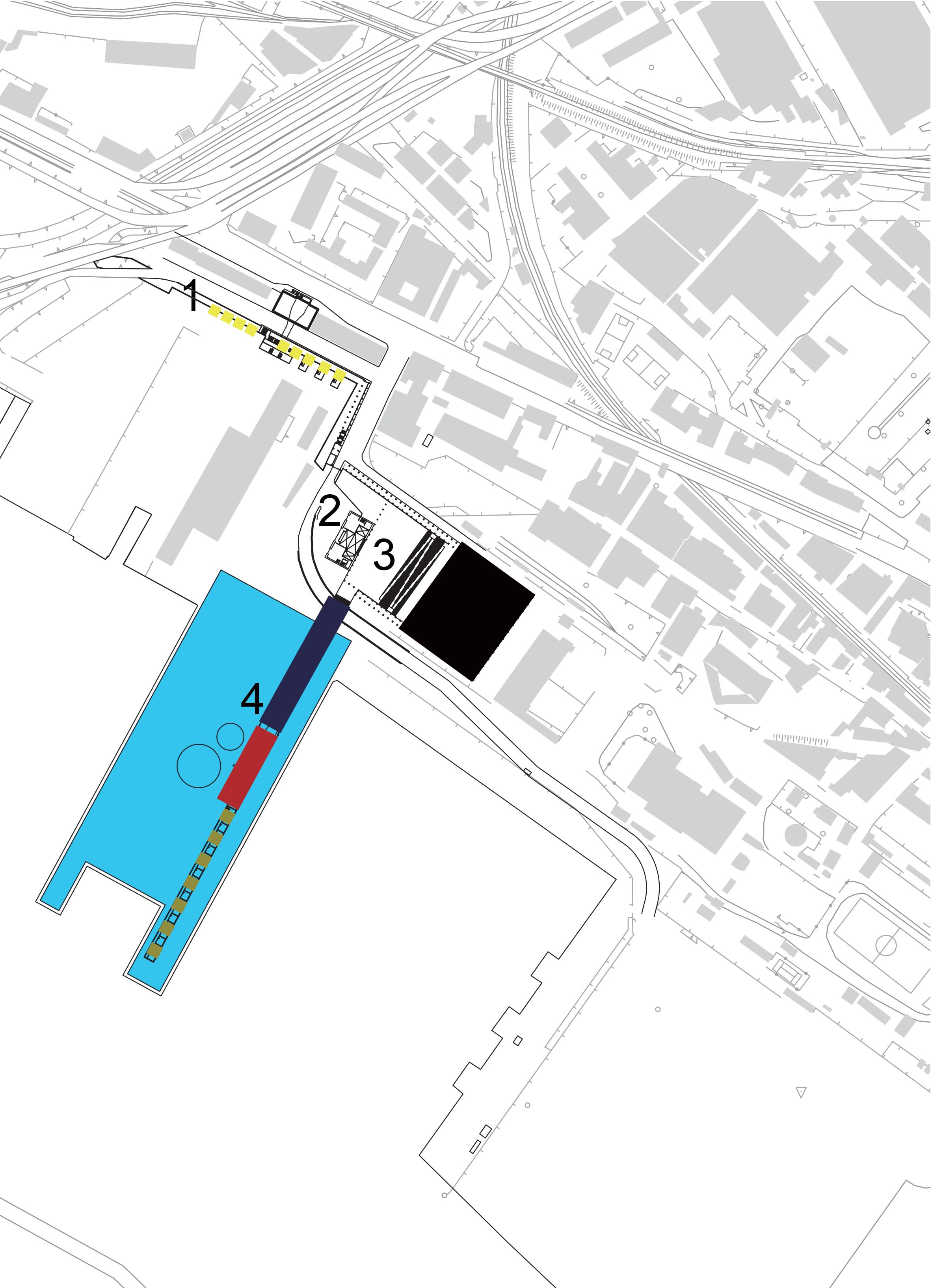

b_Masterplan. The red lines are the existing pipelines that connect the oil dock to the oil storage area today. This infrastructure line will the turned in a new linear park. (Marijn Heijnis, MSc 2 Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil, Fall 2018).

c_Mercati Napoletani on the oil dock. (Marijn Heijnis, MSc 2 Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil, Fall 2018)

Wei-Chieh proposes the construction of a geothermal power plant at the oil dock (Image d). The Volcano will be the energy. He imagines that this will provide clean energy for the city in an era beyond oil. At the same time a big thermal pool will provide hot water for public use and social interactions, recovering the relationship between people and the sea. The transition to an era beyond oil will provide new technologies and combine them with new social values. The design solution is strongly inspired by the values and spatial qualities of the city and its millenary history (Image e). The plaza, the theatre, the underground city become the points of departure for reinventing the relationship between the city and the port. The old pipelines are transformed in an underground path, the “Low line” (Image f). The underground path links the new public facilities and spaces avoiding the conflict with some port functions still in place, such as container activities. The low line guides the visitors through the spaces. The outside path builds visual relations with the volcano on one side and the city, Castel Sant’Elmo, and the sea on the other side (Image g).

d_Thermal pool on the oil dock. (Wei-Chieh Wang, MSc 2 Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil, Fall 2018)

e_Spatial qualities. (Wei-Chieh Wang, MSc 2 Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil, Fall 2018)

f_Masterplan. (Wei-Chieh Wang, MSc 2 Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil, Fall 2018)

g_Thermal pool. (Wei-Chieh Wang, MSc 2 Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil, Fall 2018)

Conclusions

History matters and can serve as a basis for design. In East Naples the presence of petroleum infrastructures does not only concern the port itself. On the contrary, it has a profound influence on the neighbouring city and the entire surrounding territory. Over the last hundred years, petroleum infrastructure has generated a spatial and cultural separation that is the point of departure for the design projects discussed here. Both students have chosen to rethink the oil dock used today for oil and gas supply of the port, city and the region. In their long-term vision this area will be the new center to rebuild a sense of community. Although different in both approach and design, the two projects have in common a translation of city values and cultural memories into the port.

The port of Naples has a strong spatial and topological connection with the oil areas behind the port. However, this proximity has never translated into concrete forms of productive and urban integration with the city and the region. On the contrary the presence of a refinery (dismantled today) and oil tanks still in use, have generated separation, fragmentation and social segregation. The proposals look at this territory as a resource, as a place to host new forms of living together. The two scenarios, beyond their feasibility, highlight an important issue, namely the necessity to change the relationship between city and port and to take advantage of spaces that the end of the oil era will generate. In this perspective, the municipality and the port should no longer think of the area behind the port should as a logistics and industrial platform at the service of the port. In the future, some areas of the port will host different activities and functions, compatible with the life of the port. Such a planning perspective can allow the port of Naples to establish new forms of integration with the city, its urban palimpsest and its memories.

Notes

[1] The new national port reform in 2016 introduced the port systems. Following the reform, the port authority of Naples has become the Central Tyrrhenian Sea Port System, incorporating the port of Castellammare di Stabia and Salerno. The reform put the three ports under the umbrella of one single port president. URL: http://www.mit.gov.it/comunicazione/news/autorita-portuale/approvato-il-decreto-riorganizzazione-dei-porti. Last access 2019-04-05.

[2] Comune di Napoli. La trasformazione della zona orientale.URL: http://www.comune.napoli.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/3485. Last access 2019-03-29.

[3] Ibid.

References

Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mar Tirreno Centrale. (2017). Piano Operativo 2017-2019 con proiezione al 2020 Revisione anno 2018.

Castigliano, M., De Martino, P., & Russo, M. (2018). Napoli: relazioni irrisolte tra porto e città. Urbanistica Informazioni.

Comune di Napoli. (2004). City plan.

Comune di Napoli. (2009). PUA DI SAN GIOVANNI A TEDUCCIO.

Corboz, A. (1998). Il territorio come palinsesto. In P. Viganò (Ed.), Ordine Sparso. Saggi sull’Arte, il Metodo, la Città, il Territorio. Milano: Franco Angeli.

De Martino, P. (2016). Land in Limbo: Understanding Planning Agencies and Spatial Development at the Interface of the Port and City of Naples. Paper presented at the International Planning History Society Proceedings, 17th IPHS Conference, History-Urbanism-Resilience,, TU Delft.

Hein, C. (2013). Between oil and water. The logistical petroleumscape. In N. B. a. M. Casper (Ed.), The petropolis of tomorrow (pp. 436-447). New York: Actar Publishers.

Hein, C. (2017). How the Fourth Industrial Revolution will change the energy landscape. BEAM. Retrieved from: from https://medium.com/thebeammagazine/how-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-will-change-the-energy-landscape-7fe155227ca9.

Hein, C. (2018). Oil Spaces: The Global Petroleumscape in the Rotterdam/The Hague Area. Journal of Urban history, 1-43. doi:10.1177/0096144217752460.

Hein, C. (2019). Designing post-carbon Dunkirk with students from TU Delft. The Beam, 8.

Hein, C., & De Martino, P. (2018). Designing post-carbon Dunkirk with the students from TU Delft. The Beam, 5.

Russo, M. (2012). Campania. Napoli Est: prove di sostenibilità. EWT/ Eco Web Town Magazine of Sustainable Design.

Russo, M. (2014). Harbour waterfront: landscapes and potentialities of a contended space. TRIA, 13 (special issue).

Russo, M. (2016). Harbourscape: Between Specialization and Public Space. In M. a. R. Carta, D. (Ed.), The Fluid City Paradigm. Waterfront Regeneration as an Urban Renewal Strategy (pp. 31-44). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Secchi, B. (2000). Prima lezione di urbanistica. Bari: Laterza.

Secchi, B., & Viganò, P. (2009). Antwerp. Territory of a new modernity. Amsterdam: Sun Publishers.

Head Image: Oil area in Naples. (Source: City plan Naples for the Ambito 13 ex Refineries)