The decision in building an entirely new port facility of national priority, what was known back then “Poland’s gateway to the world,” was made shortly after regaining independence at the end of World War I in 1918. The Treaty of Versailles guaranteed the Poles access to the sea which was just a 147 km long strip of coastline along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. It was connected to the bulk of the country by the tract known as the “Polish Corridor,” because of the fact it was located between German province lands of East Prussia and West Prussia.

Unfavorable relations with adjacent to the Polish seacoast Free City of Danzig (Gdansk), mostly unsympathetic to the needs of the new Polish state, accelerated decisions of the Polish Government to build a new seaport independent territorially and economically from influences of foreign rulers, able to guarantee the freedom of international trade exchange.

For the construction site of a future port, Polish independent maritime base Engineer Tadeusz Wenda, later chief port designer, chose an area near a small farming village and seaside resort, a town called Gdynia. It is necessary to point out that the site had never before been developed as a harbor only a local fishing settlement, so all construction had to start from scratch. The undeveloped coastal areas however, to the experienced engineer appeared to have lots of benefits, like natural protection from heavy winds provided by the Hel Peninsula, deep sea in the area even close to shore, water with low waves which also rarely freezes, favorable navigation conditions, easy access from the sea and a close distance to the already existing railway. The Polish national port site was constructed over 12 years and in 1926 the town became the city of Gdynia, however significant development was to take place. As dates show, construction lasted only a few years but it was worth all the intensive efforts. Although work began in 1921 the first stage of the ports construction was carried out slowly due to severe, pioneer conditions and financial difficulties. In 1923 the first temporary harbor for fishing boats and naval ships was opened, but it could only provide basic trans-shipment needs of small vessels. Construction continued at a slow pace until 1926 but eventually it accelerated when Polish trade had to switch to sea roads due to the outbreak of the German-Polish trade war. As a result of the miners strike in Great Britain, the Upper Silesian coal obtained new trade markets across the Baltic Sea in Scandinavia. By 1933 the port of Gdynia, which was officially completed and opened that year, accomplished excellent results of simultaneous expansion and exploitation, it also started to stand on equal footing with all other ports on the Baltic Sea and the North Sea, even those far older and more established.

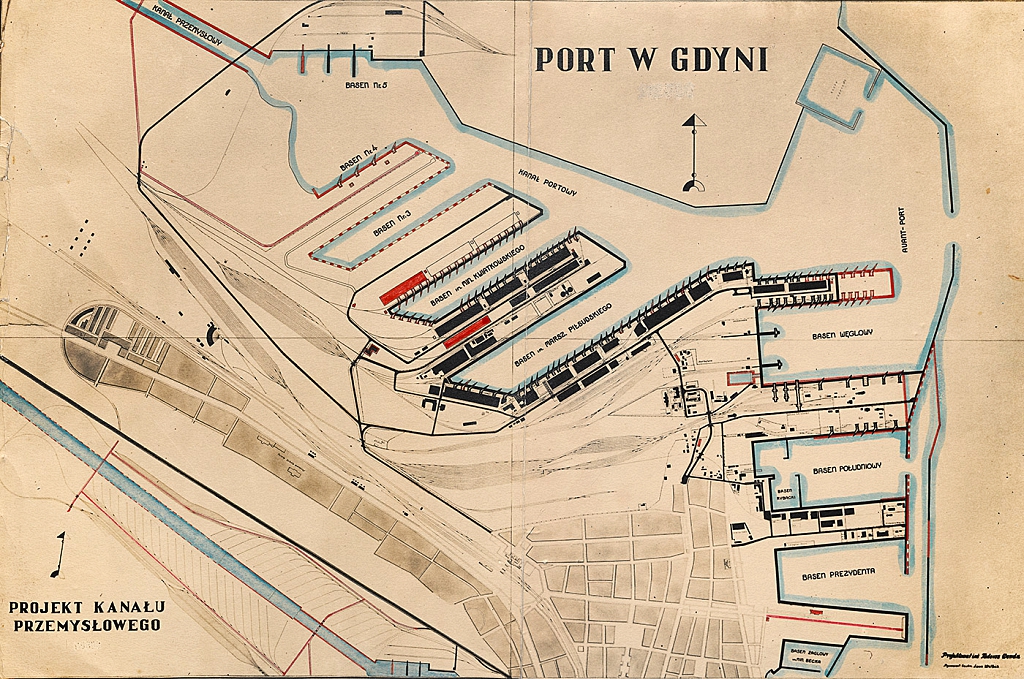

Plan of the Port of Gdynia in the 1930s by Wenda Tadeusz. (Gdynia City Museum Archives, http://gdyniawsieci.pl/obiekty-archiwum-cyfrowego/18011/)

Remarks on the ports construction and its main historical features

The port of Gdynia is defined by the time the complex had been designed and constructed, which was the 1920s and 1930s. The concepts laid out by Tadeusz Wenda assumed the construction of the inner harbor with four basins dug out and deepened in what used to be formerly land and the outer port consisting of 4 piers projecting the coastline.

Another characteristic of its construction was the usage of prefabricated reinforced-concrete box caissons to serve as a shell for quays, jetties, and breakwaters. Thanks to this innovative at that time technology, introduced in Gdynia by the Danish engineering company Højgaard & Schultz, the construction of the port in Gdynia was possible in a comparatively short time, whilst it became one of Europe’s most significant contracting assignments.

Reuse issues of heritage buildings in the port of Gdynia

Marine Station adaptation for the Emigration Museum

This formerly most prestigious public utility building in the port of Gdynia was composed of two integrated parts – the Passenger Hall and Transit Warehouse, which gained distinctive forms fulfilling diverse functions. The impressive sea passenger terminal (1932-1933) designed by the Katowice branch of Dyckerhoff & Widman, was opened to support all the passenger traffic for the Second Republic of Poland.

It is necessary to mention that while Nazi Germany occupied Poland and the port was turned into Kriegsmarine base, the building was severely damaged by Allied bombing. It was partly repaired during the war, yet the destroyed part was never rebuilt despite the Maritime Station performing its former functions after the war.

Former Marine Station in Gdynia, adaptation for the Emigration Musem, 1 Polska street, view of the building after conversion for the new museum functions. (© Anna Orchowska-Smolinska, 2018)

The return to its original form became possible in 2015 only due to the buildings conversion to a new museum facility on the map of cultural Gdynia – The Emigration Museum. Preparing the projects adaptation and the whole investment had been preceeded by wide-ranging research (in the fields of history, architecture, and conservation) and taken care of under the watchful eye of the conservatory officer.

The newly erected museum on the cultural map of Gdynia became a perfect site not only for transmitting expositions but Polish emigration narration and also a place for other culture-led projects for Tri-city citizens (metropolitan area of Gdansk, Sopot, and Gdynia) and to reach a wider audience with popular programs and the architectural heritage of modernism.

Former Marine Station in Gdynia, adaptation for the Emigration Musem, 1 Polska street, former check-in hall on the upper floor of the Transit Warehouse, nowadays the exposition hall. (© Anna Orchowska-Smolinska, 2018)

Former “Bananas” ripening room, warehouse and cold storage

Another case of the port building undergoing a major transformation is a banana ripening facility. Built by a company called “Bananas – Polski Przemysl Owocowy Sp. Akc.” and design architects Eliza Unger and Bronislaw Wondrasch in cooperation with engineer Oswald Unger in 1939. A special feature of the group of buildings in the port of Gdynia represented by “Bananas”, was a combination of functions – storage and offices with different specialist types of operation (e.g., standard and cold storage, auction halls, and operational rooms) and sometimes even residential purposes. The building was given a careful design rich in details and solutions, among which were appealing recessed porticos from each of the flanking sides, a refined pattern of two-color brick elevations, expressive under eaves frieze and more. Though the building itself has had a rather compact form and was easily converted to new roles, the investor decided to demolish most of the tissue leaving only two of its façades. Apart from that, the entire plot enlarged by neighboring parcels (emptied of other buildings with historical and architectural values), was filled-out with a new structure supplementing the remains of the former “Bananas” building. The original elevations were left as curtain walls, with slight alterations, preserved and subjected to conservation works. The main difference from the original appearance is that the building used to be detached, currently however, it seems the new structure absorbed the historical one.

Former “Bananas” Ripening Room, Warehouse and Cold store in the port of Gdynia, after rebuild and expansion of its original structure, view from Polska street. (© Anna Orchowska-Smolinska, 2018)

The remains of “Union” Oil Mill complex

The case of the former Oil Mill in the port of Gdynia is quite a drastic example of threats the industrial architectural heritage is exposed to. Along the Indian Wharf, the part of the port where the refining industry complexes related to maritime transport had been built, situated was the Rice Hulling Mill, the Oil Mill, and the Grain Elevator. The same as others, the Oil Mill complex (1930-1931) designed by Wayss & Freytag AG, was composed of several buildings of different forms and sizes. The most distinguished element was meant to be a 30 plus meter high oilseeds silo in a reinforced concrete frame structure with a massive body expanding towards the inner part of the pier. This industrial complex of high historical values had been desolated due to the loss of functionality for several years. The company which decided to start operating in this area of significant economic value needed an empty plot to construct a large-scale, single-space production hall. Thanks to the intervention of the conservation authorities, the entire complex had not been destroyed. The front part composed of three pseudo-towers, which used to face the port basin, had been left “untouched”. This word is the most appropriate to what happened because the new industrial hall made of steel construction with metal cladding is not combined with the selfstanding part of the former silo, though from a longer distance it appears there are elements of the same building. Moreover, the newly erected structure fills-out almost the entire plot and is painted in wide yellow and blue stripes, in corporate colors.

The remains of the Oil Mill had not been taken care of by conservators hence its destruction is progressing. We should ask the question if this way of dealing with heritage preservation contributes to the preservation of the visual character of the complex within the port landscape. This example shows clearly the destruction of historic structures taking into account the redevelopment of the port area.

The remains of “Union” Oil Mill, on Indian Pier in the port of Gdynia, after the demolition of the entire complex apart the front part of the silos for oilseeds, and building a new structure which fills-out the whole plot. (© Anna Orchowska-Smolinska, 2018)

Conclusions

Taking into account the examples of reuse heritage port elements and its substance, the city of Gdynia recently faced a notable growth in public interest of interwar cultural heritage, moreover particularly its modern industrial architecture. This resulted in a more significant then ever need amongst residents and tourists in visiting the port and learning about the emergence of it, the architecture and constructions, its trading past, and present operation. An obligation to preserve the resources of the port heritage and to provide the audience with access to places of historical, architectural, scientific or other particular importance rests on the hosts, which are in this case the Port of Gdynia Authority and the City of Gdynia. Nevertheless, it needs to be added; the port is a territory of present-day port activities which had not moved to a different port space in the course of development. That is why in recent years the port has been undergoing significant transformations and modernizations which focus mostly on release of plots for potential investments or simply storage purposes. This process applied to the area is most attractive economically and also most important for historical assets of cultural heritage resources.

References

Orchowska-Smolinska, A. (2013), Architecture and special arrangement of Gdynia’s seaport between the two World Wars as a cultural Heritage, PhD thesis, Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk.

Hirsch, R. (2016) Protection and conservation of modernistic architecture in Gdynia, Gdansk University of Technology, Gdansk.

Soltysik, M. (1993), Gdynia the Inter-war City. Town Planning and Architecture, Polish Scientific Publishers PWN, Warsaw.

Orchowska-Smolinska, A., Jaskiewicz-Sojak, A. (2009), Modernist Industrial Architecture and Its Protection – the Port of Gdynia, International Conference: Modernism in Europe – Modernism in Gdynia. Architecture of 1920s and 1930s and Its Protection, Gdynia.

Head Image: Former Marine Station in Gdynia – (from the left). The Transit Warehouse and The Passenger Hall, adaptation for the Emigration Musem, 1 Polska street, view of the building from the waterfront. (© Anna Orchowska-Smolinska, 2018)