╔

Il lungomare di Catania e la scogliera Larmisi

Negli ultimi decenni la dismissione di infrastrutture portuali o ferroviarie, così come interventi per il cambiamento di tracciato di quest’ultime o di interramento, sono stati il punto di partenza di processi di trasformazione delle città, in quanto occasioni per inserire attrezzature, nuove funzioni e attività culturali, economiche e turistiche (Gabrielli, 2004).

Il tema del waterfront, ossia la “porzione di tessuto della città che sta sul margine, a contatto con l’acqua” (Bruttomesso, 2007), è diventato, quindi, di grande attualità, coinvolgendo ambiti sia portuali che non (litorali costieri, lungofiumi o lungo canali) grazie all’elevato potenziale di trasformazione (Carta, 2006).

In numerosi interventi, il waterfront redevelopment ha assunto il ruolo di motore per la rigenerazione della città, o di parti di essa, in quanto occasione per promuovere lo sviluppo sostenibile (Carta, 2006).

Over the last decades, the decommissioning of port or railway infrastructures, as well as interventions to change their layout or to bury them, have been the starting point of city transformation processes, as occasions to insert equipment, new functions and cultural, economic and tourist activities (Gabrielli, 2004).

The theme of the waterfront, i.e. the “portion of the fabric of the city that lies on the edge, in contact with the water” (Bruttomesso, 2007), has therefore become highly topical, involving both port and non-port areas (coastal littorals, along rivers or along canals) thanks to its high transformation potential (Carta, 2006).

In numerous interventions, the waterfront redevelopment has assumed the role of a motor for the regeneration of the city, or parts of it, as an opportunity to promote sustainable development (Carta, 2006).

Background

Background

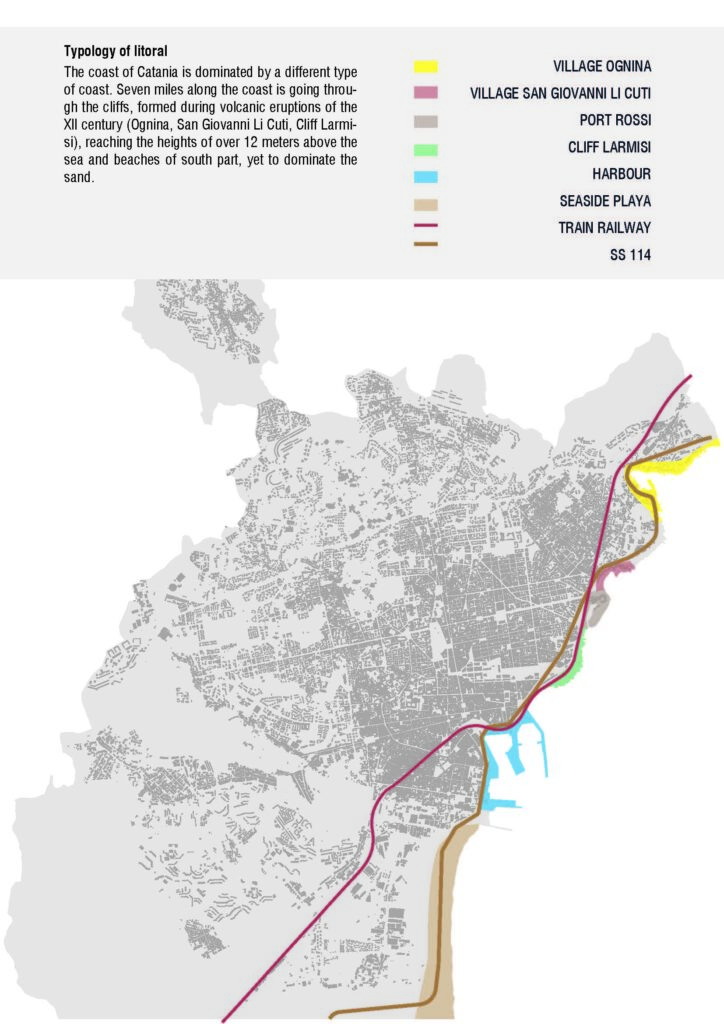

La città di Catania si affaccia sul mare per circa 9 km, oltre ai 2,5 km del litorale costiero sabbioso a sud, conosciuto come la Playa, dal quale si susseguono, in direzione nord, la foce del torrente Acquicella, il porto commerciale, la scogliera de Larmisi, il porto Caito, conosciuto anche come porto turistico Rossi, ed il lungomare nord con gli antichi borghi marinari di San Giovanni Li Cuti e di Ognina.

Dei suddetti chilometri di linea costiera, circa due sono interessati dal porto, mentre gli altri sono costituiti da tratti lavici di grande pregio naturalistico per la particolarità morfologica, per le forme e per la vegetazione spontanea, che si assestano su quote comprese tra otto e undici metri.

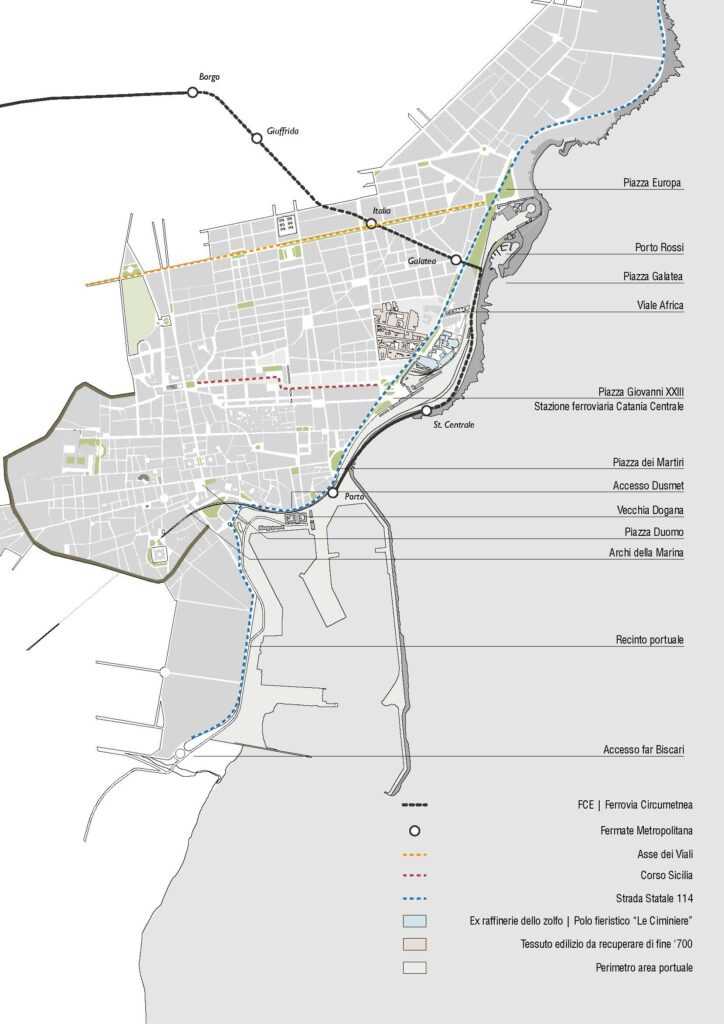

Il litorale costiero che si estende dall’area portuale fino a piazza Europa, per circa due chilometri lungo la scogliera de Larmisi, attualmente occupato dai percorsi ferroviari delle Ferrovie dello Stato (FS) [1], è oggetto di ampio dibattito nella città da diversi anni, in attesa di possibili trasformazioni urbane ed infrastrutturali, in previsione sia della redazione e approvazione di un Piano Urbanistico Generale (PUG), che della realizzazione del cosiddetto “Nodo Catania”, un progetto di Rete Ferroviaria Italiana (RFI) [2], che prevede l’interramento della linea ferrata tra piazza Europa e piazza dei Martiri. Ciò perché il tracciato ferroviario nel tratto da Cannizzaro a Piazza Europa, dopo un percorso a cielo aperto, che scavalca fra l’altro la circonvallazione nord ad Ognina, si immette in galleria fino a piazza Europa e, successivamente, a cielo aperto arriva fino alla stazione ferroviaria “Catania Centrale” e a piazza Martiri. Quest’ultima è il punto di inizio del “Passiatore”, la storica passeggiata a mare dei catanesi, che si estende lungo i binari fino alla stazione ferroviaria, realizzata nell’Ottocento in sostituzione del passeggio esistente lungo il tracciato delle Mura di Carlo V, ostruito dalla realizzazione del viadotto ferroviario degli “Archi della Marina”.

Gran parte dell’attuale centro storico della città, il cosiddetto tessuto di impianto “camastriano”, si affaccia sull’area portuale, chiusa da una cinta doganale. Il successivo sviluppo urbano del XIX e XX secolo, invece, interessa la scogliera de Larmisi, risalente forse al 4-5000 a.C., probabilmente la prima lava a raggiungere il territorio catanese ancora non abitato.

The city of Catania overlooks the sea for about 9 km, in addition to the 2.5 km of sandy coastline to the south, known as the Playa, from which the mouth of the Acquicella torrent, the commercial harbour, the Larmisi reef, the Caito harbour, also known as the Rossi marina, and the northern waterfront with the ancient seaside villages of San Giovanni Li Cuti and Ognina follow in a northerly direction.

Of the aforementioned kilometres of coastline, about two are affected by the harbour, while the others consist of lava stretches of great naturalistic value due to their morphological peculiarities, shapes and spontaneous vegetation, which settle at heights of between eight and eleven metres.

The coastal shoreline that stretches from the port area to Piazza Europa, for about two kilometres along the Larmisi cliff, currently occupied by the railway tracks of the Ferrovie dello Stato [1], has been the subject of extensive debate in the city for several years, in anticipation of possible urban and infrastructural transformations, in anticipation of both the drafting and approval of a General Urban Plan, and the realisation of the so-called ‘Catania Node’, a project of the Italian Railway Network [2], which envisages the burying of the railway line between Piazza Europa and Piazza dei Martiri.

The latter is the starting point of the ‘Passiatore’, the historic seaside promenade of the Catanese, which extends along the tracks to the railway station, built in the 19th century to replace the existing promenade along the route of the Walls of Charles V, obstructed by the construction of the ‘Archi della Marina’ railway viaduct.

Much of today’s historic city centre, the so-called ‘Camastrian’ urban plan, overlooks the port area, which is enclosed by a customs wall. Subsequent urban development in the 19th and 20th centuries, on the other hand, involved the Larmisi cliff, possibly dating back to 4-5000 B.C., probably the first lava to reach the uninhabited territory of Catania.

Da sinistra in alto: piazza Europa, piazza Galatea, il porto Caito, piazza Giovanni XXIII, il “Passiatore” di piazza dei Martiri, il litorale costiero de Larmisi.

From left to top: Piazza Europa, Piazza Galatea, the Caito harbour, Piazza Giovanni XXIII, the ‘Passiatore’ in Piazza dei Martiri, the Larmisi cliff.

Qui la costa è fortemente penalizzata dalla presenza della ferrovia, della stazione “Catania Centrale”, principale scalo merci e passeggeri della città, e del deposito locomotive nei pressi di piazza Europa, che hanno impedito nel tempo la piena fruibilità della costa, determinando così una barriera tra il mare ed il tessuto urbano. Tale rapporto in quest’area è unico e di grande valore naturalistico e ambientale, per la presenza della scogliera creata dalle lave, tuttavia fruibile solo in prossimità del porto turistico, gestito da privati, sito in corrispondenza del Deposito Locomotive di piazza Europa e ricavato, negli anni sessanta, da un’insenatura della scogliera rocciosa.

Altra grande rilevanza, per il valore storico e culturale, è legata alla presenza, nei pressi di piazza Giovanni XXIII, del polo fieristico “Le Ciminiere“, tra i primi esempi di archeologia industriale in Italia, testimonianza, insieme ad altri fabbricati dismessi presenti nell’area, dei depositi e delle raffinerie di zolfo, che costituirono alla fine dell’Ottocento l’attività industriale più importante della città di Catania e della Sicilia. Infatti, lungo il Viale Africa, proseguimento della Strada Statale (SS) 114, che è il principale asse di accesso da sud alla città, è presente un tessuto edilizio caratterizzato da vecchi opifici industriali in attesa di riqualificazione, sebbene siano già stati realizzati alcuni interventi puntuali di recupero.

Inoltre, lungo la fascia urbana immediatamente retrostante alla scogliera si susseguono, da nord, piazza Europa, luogo nevralgico e punto di partenza del cosiddetto “Asse dei viali”, l’asse viario urbano principale che attraversa, in direzione est-ovest, la città e su cui gravitano numerose funzioni (residenziale, commerciale) ed attività (servizi, attrezzature comunali ed istituzioni); piazza Galatea e viale Ionio, altro importante asse commerciale; piazza Giovanni XXIII, uno dei nodi principali della mobilità urbana. Tali presenze, insieme all’elevata accessibilità garantita dalla presenza delle stazioni della linea metropolitana, “Galatea” e “Catania Centrale”, la stazione RFI “Catania Centrale”, che assorbe la quasi totalità del traffico passeggeri della città, e dai terminal dei bus urbani ed extraurbani, situati in piazza Giovanni XXIII, conferiscono un ruolo strategico all’area, considerata uno dei principali poli attrattori del territorio.

Here the coast is strongly penalized by the presence of the railway, the “Catania Centrale” station, the city’s main freight and passenger port, and the locomotive depot near Piazza Europa, which have prevented over time the full usability of the coast, thus determining a barrier between the sea and the urban fabric. This relationship in this area is unique and of great naturalistic and environmental value, due to the presence of the cliff created by the lavas, however, usable only near the marina, managed by private individuals, located at the Locomotive Depot in piazza Europa and obtained, in the 1960s, from an inlet of the lava cliff.

Another great relevance, for historical and cultural value, is related to the presence, near Piazza Giovanni XXIII, of the exhibition center “Le Ciminiere,” among the first examples of industrial archaeology in Italy, evidence, along with other disused buildings in the area, of the sulfur deposits and refineries, which constituted at the end of the nineteenth century the most important industrial activity in the city of Catania and Sicily. In fact, along Viale Africa, a continuation of road SS 114, which is the main axis of access from the south to the city, there is a building fabric characterized by old industrial factories awaiting redevelopment, although some punctual rehabilitation work has already been carried out.

In addition, along the urban strip immediately behind the cliff are, from the north, Piazza Europa, the nerve center and starting point of the so-called “Axis of the avenues,” the main urban road axis that crosses, in an east-west direction, the city and on which gravitate many functions (residential, commercial) and activities (services, municipal facilities and institutions); Piazza Galatea and Viale Ionio, another important commercial axis; and Piazza Giovanni XXIII, one of the main nodes of urban mobility. These presences, together with the high accessibility guaranteed by the presence of the subway line stations, “Galatea” and “Catania Centrale,” the railway station “Catania Centrale,” which absorbs almost all of the city’s passenger traffic, and the urban and suburban bus terminals, located in Piazza Giovanni XXIII, give a strategic role to the area, which is considered one of the main poles of attraction in the area.

Differenti tipologie costiere lungo il waterfront di Catania. (Fonte: Elaborazione degli autori).

Different coastal typologies along the Catania waterfront. (Source: Authors’ elaboration).

Inquadramento delle aree portuali di Catania. (Fonte: Elaborazione degli autori).

Framing of the port areas of Catania. (Source: Authors’ elaboration).

Dinamiche storiche urbane

Urban Historical Dynamics

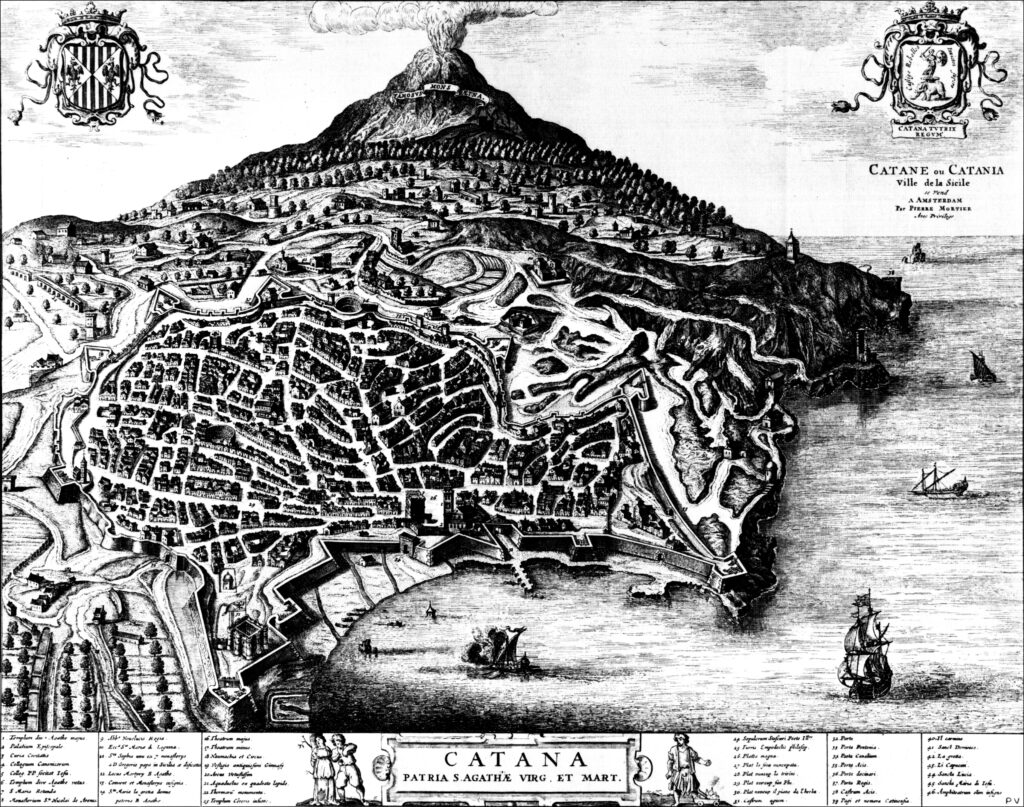

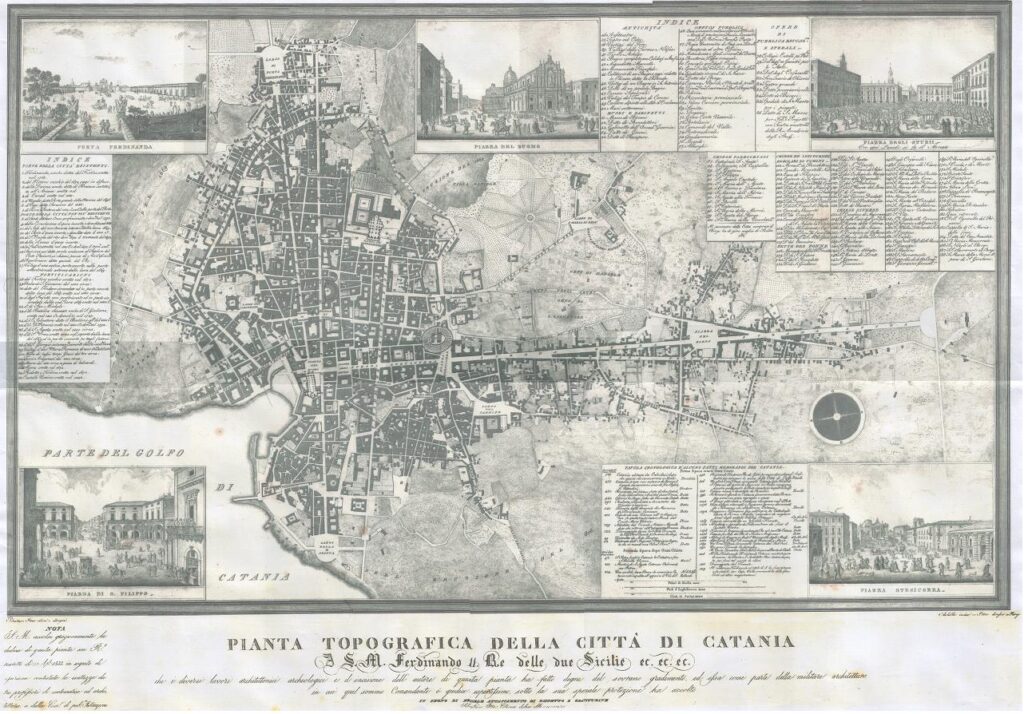

Dal XVI al XVII secolo la morfologia della città, fondata nel 729 a.C. ad opera dei coloni Greci Calcidesi, è strettamente connessa al tracciato della cinta muraria spagnola, realizzata per volere dell’imperatore Carlo V, che racchiudeva completamente la città, al di là della quale le uniche presenze importanti erano il convento di San Francesco di Paola sul piano de Larmisi e la chiesetta del SS. Salvatore sugli scogli di Porto Pontone (De Luca, 2012).

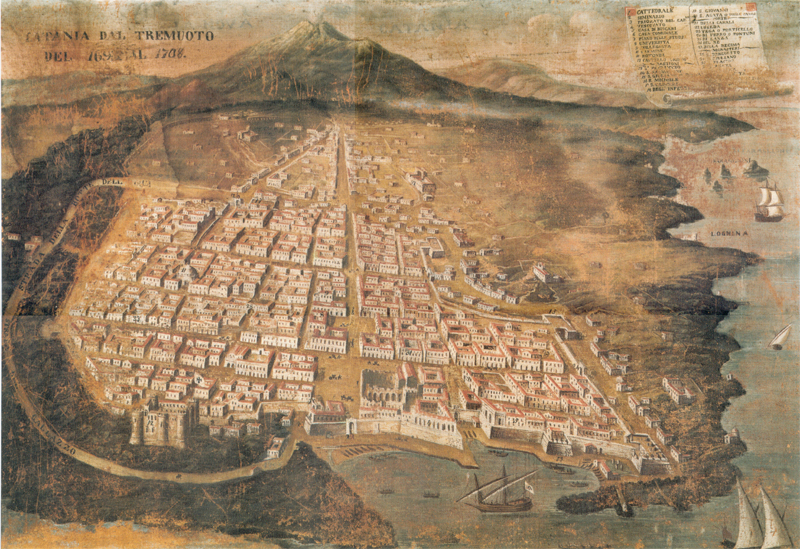

Nel corso della sua storia Catania è stata più volte distrutta da eruzioni vulcaniche che più volte hanno raggiunto il mare, la più imponente nel 1669, e da terremoti, i più catastrofici nel 1169 e nel 1693. In seguito a quest’ultimo, che rase al suolo Catania, la città rivelò una grande capacità di ripresa, eliminando o rigenerando il patrimonio abitativo rimasto. La ricostruzione della città fu opera di Giuseppe Lanza Duca di Camastra, ingegnere militare, inviato dal re di Spagna, che insieme a Carlos de Grunembergh, anch’esso ingegnere militare, decise di tracciare le nuove strade secondo delle direttrici ortogonali (cardo e decumanus), quali direzioni principali delle strade, che si sarebbero intersecati ad angolo retto attorno al duomo (uno dei pochi edifici non completamente distrutti) che restava il cuore pulsante della città (Dato, 1983).

From the 16th to the 17th century, the morphology of the city, founded in 729 B.C. by Chalcidian Greek settlers, was closely linked to the layout of the Spanish city wall, built at the behest of Emperor Charles V, which completely enclosed the city, beyond which the only important presences were the convent of San Francesco di Paola on the piano de Larmisi and the small church of SS. Salvatore on the rocks of Porto Pontone (De Luca, 2012).

Throughout its history Catania has been repeatedly destroyed by volcanic eruptions that repeatedly reached the sea, the most impressive in 1669, and by earthquakes, the most catastrophic in 1169 and 1693. Following the latter, which razed Catania to the ground, the city revealed great resilience by removing or regenerating the remaining housing stock. The reconstruction of the city was the work of Giuseppe Lanza Duca di Camastra, a military engineer, sent by the King of Spain, who together with Carlos de Grunembergh, also a military engineer, decided to lay out the new streets according to orthogonal directions (cardo and decumanus), as the main directions of the streets, which would intersect at right angles around the cathedral (one of the few buildings not completely destroyed) that remained the beating heart of the city (Dato, 1983).

Da sinistra: veduta di Catania dopo il 1575 (Fonte: P. Mortier); veduta di Catania nel 1708 (Fonte: Autore sconosciuto); planimetria di Catania nel 1833 (Fonte: Sebastiano Ittar).

From left: view of Catania after 1575 (Source: P. Mortier); view of Catania in 1708 (Source: Author unknown); plan of Catania in 1833 (Source: Sebastiano Ittar).

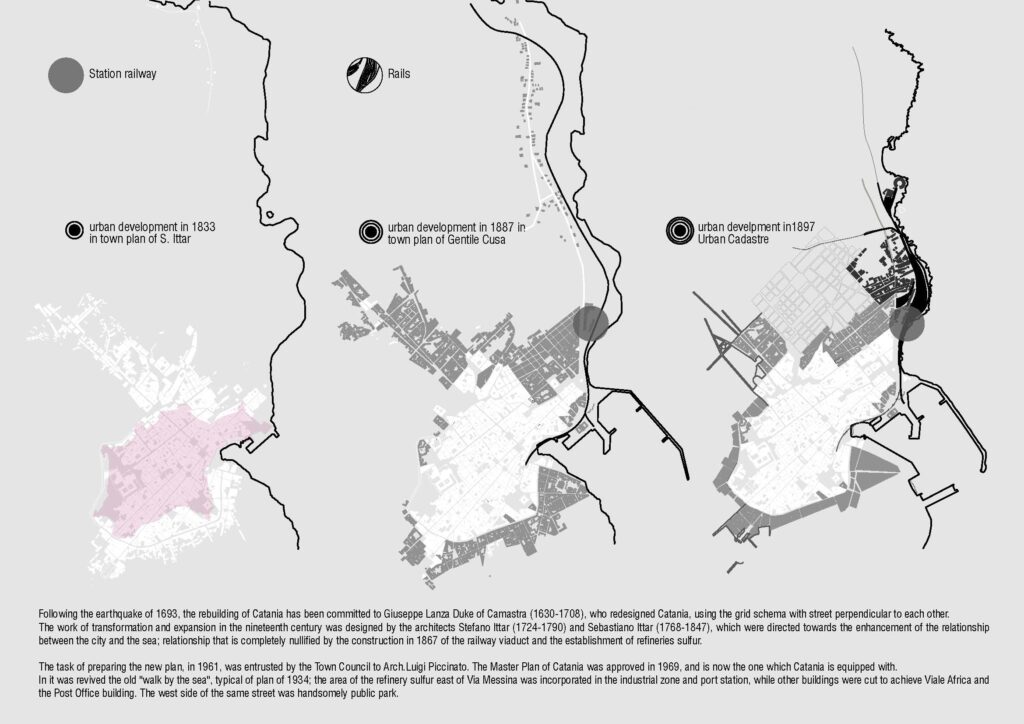

Sull’onda della Rivoluzione industriale, e in seguito alla grande richiesta di materie prime e di minerali, la Sicilia ebbe il primato per la produzione di zolfo in Europa; nell’isola si crearono numerose zolfare concentrate nella provincia di Agrigento e di Caltanissetta, mentre la lavorazione era rimandata alle province spagnole. Nel 1835 per valorizzare gli insediamenti industriali nati nella zona de Larmisi, prese corpo l’attuale via Messina, che con un percorso rettilineo giunge fino alla zona del golfo di porto Ulisse, per proseguire verso i paesi limitrofi della costa.

La vicenda urbanistica più rilevante, che ha determinato l’attuale assetto dell’area, fu la costruzione, a partire dal 1866, della ferrovia Messina-Catania-Siracusa. Il progetto prevedeva un percorso costiero, così come avvenuto per altre città italiane, nonostante una proposta di spostare a monte la linea ferrata per evitare la costruzione di una cinta di ferro tra la città ed il mare.

Per connettere, mediante la ferrovia, l’estremo lembo nord della Sicilia e il porto di Messina alle zone produttive della fascia orientale e zolfifere di quella centro-orientale dell’Isola, fu inaugurata nel 1867 la stazione Catania Centrale, lungo la scogliera de Larmisi e, nel 1869 fu inaugurato un viadotto in muratura, detto “Archi della Marina”, che collega ancora oggi la stazione di Catania Centrale all’imbocco della galleria dell’Acquicella.

Nello stesso anno anche il porto fu collegato alla Stazione di Catania Centrale mediante un raccordo in discesa.

In seguito, nelle vicinanze fu realizzata una cittadella industriale per la raffinazione in situ dello zolfo, arrivato dalle miniere e successivamente esportato per via ferroviaria e marittima. Si cominciò a delineare un tessuto urbano frammisto di residenze e opifici industriali, i principali impianti erano forni per la fusione e mulini per la raffinazione, allocati in grandi capannoni rettangolari con copertura a “capanna”, dai quali si ergono tuttora le canne fumarie alte all’incirca una trentina di metri. La costruzione delle raffinerie continuò fino al 1905, periodo di massima produzione di zolfo (Rebecchini et al., 1991).

In the Industrial Revolution period, as a result of the great demand for raw materials and minerals, Sicily was given the record for sulfur production in Europe; numerous sulfur mines were created on the island, concentrated in the provinces of Agrigento and Caltanissetta, while processing was deferred to the Spanish provinces. In 1835, in order to enhance the industrial settlements that had sprung up in the de Larmisi area, the present-day Via Messina took shape, with a straight route reaching as far as the Gulf of Ulysses harbor area and continuing to the neighboring towns on the coast.

The most relevant urban planning event, which determined the current layout of the area, was the construction, starting in 1866, of the Messina-Catania-Siracusa railway. The project envisioned a coastal route, as was the case with other Italian cities, despite a proposal to move the rail line upstream to avoid the construction of an iron wall between the city and the sea.

In order to connect, by means of the railroad, the extreme northern edge of Sicily and the port of Messina to the productive areas of the eastern and sulfur-bearing strip of the central-eastern part of the island, the Catania Centrale railway station was inaugurated in 1867, along the de Larmisi cliff, and, in 1869, a masonry viaduct, known as the “Archi della Marina,” was inaugurated, which still connects the Catania Centrale station to the mouth of the Acquicella tunnel.

In the same year, the port was also connected to Catania Central Station by a downhill railroad junction.

Later, an industrial citadel was built nearby for the in situ refining of sulfur, which arrived from the mines and was later exported by rail and sea. An urban fabric interspersed with residences and industrial factories began to emerge, the main facilities being smelting furnaces and refining mills, allocated in large rectangular sheds with “gabled” roofs, from which the flues, roughly thirty meters high, still rise. Construction of the refineries continued until 1905, the period of maximum sulfur production (Rebecchini et al., 1991).

Lo sviluppo della città di Catania, 1833-1897. (Fonte: Elaborazione degli autori).

The development of the city of Catania, 1833-1897. (Source: Authors’ elaboration).

Nel dopoguerra, le miniere siciliane entrarono in crisi, cessando le attività, per cui gli stabilimenti furono abbandonati. Con la realizzazione di viale Africa la cittadella dello zolfo venne divisa in due sezioni. Quella ad est confinante con le ferrovia, gravemente danneggiata nel corso dell’ultimo conflitto, fu abbandonata del tutto, mentre quella ad ovest fu riconvertita in diverse attività commerciali, artigianali ed industriali.

Negli anni ottanta Ferrovie dello Stato S.p.A., che attualmente offrono un servizio ferroviario a prevalente carattere di lunga percorrenza, per le linee Messina-Catania-Siracusa e Catania-Palermo, hanno mostrato esigenza di risolvere in cosiddetto “Nodo Catania” con il totale raddoppio della ferrovia in ambito urbano, proponendo progetti in affiancamento al tracciato esistente. L’ipotesi iniziale di uno spostamento totale del percorso per andare verso il nord della città, è stata successivamente abbandonata in quanto troppo onerosa. Successivamente, è stato sviluppato nel 2003 il progetto preliminare [3] del “Nodo di Catania” [4] di RFI, nell’ambito della Legge Obiettivo [5], che prevede una serie di interventi nel territorio comunale di Catania che si inseriscono nel più ampio contesto della direttrice Messina-Catania-Palermo, facente parte del corridoio Scandinavo- Mediterraneo della Rete di trasporto Trans-Europea TEN-T [6].

Negli ultimi anni, sono state realizzate alcune nuove fermate all’interno dell’area urbana, tra le quali una fermata passeggeri, denominata Europa nei pressi dell’omonima piazza, nell’ottica di sviluppo di un servizio metropolitano costiero da Taormina. Più recentemente, in merito al Nodo ferroviario di Catania, lo scorso 22 maggio 2024 è stato firmato un Protocollo d’intesa tra la Città metropolitana di Catania e le società del Gruppo FS – Rete Ferroviaria Italiana e FS Sistemi Urbani. Inoltre, è stato avviato dall’Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mare di Sicilia Orientale (AdSP-MSO) l’iter per la predisposizione del nuovo Piano Regolatore Portuale di Catania, presentato il 12 marzo scorso alla Giunta Comunale. La proposta mira a promuovere la vocazione turistica e passeggeri del porto e ha una visione strategica per promuovere lo sviluppo sostenibile del porto stesso e della relazione con la città. Il progetto prevede, tra i numerosi interventi, l’espansione della struttura esistente a nord e la creazione di una nuova darsena e di una nuova diga destinata alle grandi navi, in corrispondenza della scogliera de Larmisi, sotto alla Stazione Centrale.

Pertanto, l’interramento della suddetta stazione e della ferrovia lungo la scogliera de Larmisi, a seguito della realizzazione di un nuovo tracciato interrato dalla suddetta fermata Europa alla Stazione Catania Acquicella, vicino all’aeroporto, si configurano come un intervento volto alla restituzione delle aree ferroviarie alla città. Inoltre, rappresenterebbe una grande potenzialità per il waterfront, poiché verrebbero rese disponibili aree di grande valore ambientale e paesaggistico, nelle quali sono previsti interventi di rigenerazione urbana, da realizzare in accordo con il Comune di Catania, in coerenza con il redigendo PUG e con il protocollo appena firmato, e con l’AdSP-MSO, in linea con quanto previsto nel PRP.

After the war, the Sicilian mines went into crisis, ceasing operations, so the plants were abandoned. With the construction of Africa Avenue, the sulfur citadel was divided into two sections. The one to the east bordering the railroad, which was severely damaged during the last conflict, was abandoned altogether, while the one to the west was reconverted into various commercial, craft and industrial activities.

In the 1980s Ferrovie dello Stato, which currently offers a predominantly long-distance railway service, for the Messina-Catania-Siracusa and Catania-Palermo lines, showed need to solve in so-called “Catania Node” with the total doubling of the railway in the urban area, proposing projects alongside the existing route. The initial hypothesis of a total shift of the route to go north of the city was later abandoned as too costly. Subsequently, the preliminary design [3] of Italian Railway Network “Catania Node” [4] was developed in 2003, under the Objective Law [5], which envisages a series of interventions in the Catania municipal area that fit into the broader context of the Messina-Catania-Palermo route, part of the Scandinavian-Mediterranean corridor of the Trans-European Transport Network TEN-T [6].

In recent years, a number of new stops have been built within the urban area, including a passenger stop called Europa near the square of the same name, with a view to developing a coastal metropolitan service from Taormina. More recently, regarding the Catania Railway Node, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed on May 22, 2024 between the Metropolitan City of Catania and the Ferrovie dello Stato Group companies – Italian Railway Network and Ferrovie dello Stato Urban System. In addition, the Port System Authority of the Sea of Eastern Sicily has started the process of preparing the new Port Master Plan of Catania, which was presented to the City Council on March 12. The proposal aims to promote the port’s tourism and passenger vocation and has a strategic vision to promote the sustainable development of the port itself and its relationship with the city. The project includes, among many interventions, the expansion of the existing structure to the north and the creation of a new dock and a new seawall intended for large ships, at the de Larmisi reef, below the Central Station.

Therefore, the burying of the aforementioned station and the railway along the de Larmisi cliff, following the construction of a new underground track from the aforementioned Europa stop to the Catania Acquicella Station, near the airport, would be configured as an intervention aimed at returning the railway areas to the city. In addition, it would represent a great potential for the waterfront, since areas of great environmental and landscape value would be made available, in which urban regeneration interventions are planned, to be carried out in agreement with the Municipality of Catania, in coherence with the drafting General Urban Plan and with the protocol just signed, and with the Port System Authority of the Sea of Eastern Sicily, in line with what is foreseen in the PRP.

I piani a confronto: la riqualificazione mancata

The Plans Compared: The Missed Redevelopment

Come già accennato, da sempre la zona si trova al centro del dibattito urbanistico della città, sin dalla scelta del luogo per la realizzazione della ferrovia, che ha conferito uno specifico assetto infrastrutturale all’area. Tuttavia, la città è ancora in attesa di un nuovo PUG poiché, nonostante il susseguirsi di proposte negli ultimi vent’anni, il PRG, redatto dall’architetto Luigi Piccinato nel 1964, ed approvato nel 1969, costituisce ancora oggi lo strumento urbanistico comunale vigente.

Tale piano si limita a circoscrivere la fascia tra viale Africa e la scogliera de Larmisi ”Area Industriale-Portuale-Ferroviaria”, individuando aree verdi senza dare, però, una specifica definizione agli interspazi circostanti alla linea ferrata. Inoltre si pianifica il massimo sfruttamento del suolo e delle risorse invece che il riuso, la riqualificazione dell’esistente e il recupero del rapporto della città con il mare.

Successivamente sono state attivate alcune procedure di varianti e di deroghe al PRG, tra le quali una delibera del Consiglio Comunale del 1979 che ha inserito le ex raffinerie, per la rilevanza della loro memoria storica, tra le zone soggette a Piano di Recupero, e nel 1989 vi è stato realizzato il Centro fieristico “Le Ciminiere”, opera dell’architetto Giacomo Leone. Oggi il centro, che ha una superficie di quasi 25.000 metri quadrati ed è adibito a centro polifunzionale (fieristico, espositivo e congressuale), è un centro nevralgico culturale per l’intero territorio comunale rappresentando una grande potenzialità per l’intera area. Infatti, ospita, tra l’altro, un museo permanente sullo sbarco in Sicilia del 1943, svariate mostre temporanee, fiere e congressi, ed è utilizzato anche per concerti, rappresentazioni teatrali e cinematografiche.

Un primo accenno alla volontà di riqualificare e valorizzare l’area lungo la scogliera de Larmisi, si riscontra nella proposta di Piano Regolatore Generale del 1994, nella quale Pierluigi Cervellati, pur

mantenendo il tracciato ferroviario in superficie, manifesta la volontà di creare una sorta di waterfront, proponendo una banchina attrezzata a scavalco dei binari destinata ad area pedonale, direttamente accessibile in alcuni punti; la rifunzionalizzazione del vecchio deposito delle locomotive; la riqualificazione degli edifici dismessi lungo il viale Africa, destinati a servizi di interesse comune e la ridefinizione nei pressi di piazza Galatea, di aree verdi. Tuttavia, l’architetto Cervellati, piuttosto che risolvere le criticità formulate, si attiene alla definizione ed interpretazione degli interspazi come spazi di risulta, sulla scorta dell’infrastruttura ferroviaria e di quanto già esistente.

Il pieno recupero e fruizione del waterfront sono punti nodali della proposta di Oriol Bohigas, dello studio MBM Arquitects, autore del piano di Barcellona per le Olimpiadi del 1992, incaricato nel 2004 dall’Amministrazione comunale di una progettazione preliminare della fascia costiera compresa tra il porto commerciale ed Ognina. L’architetto spagnolo, in seguito al progetto preliminare di RFI, sceglie l’interramento della linea ferrata e della stazione, al fine di programmare l’integrabilità territoriale dell’area costiera ed aumentare la fruibilità dello spazio urbano da parte dei cittadini. Attraverso il disegno del fronte a mare, con forme nuove in grado di ridare qualità al luogo, prevede la rifunzionalizzazione del depósito ferroviario e degli edifici dismessi, la realizzazione di strutture turistiche di lusso, il tracciamento di una strada lungo la costa, il prolungamento di un asse trasversale al viale Africa fino al mare e la realizzazione di un adiacente parcheggio in superficie, oltre che la realizzazione di un porto turistico a nord della Diga foranea, quest’ultimo ripreso dalle successive proposte di PRG. Manca, tuttavia, un progetto integrato che contempli al suo interno l’intermodalità, non favorendo la viabilità pedonale in alcun caso.

L’abbassamento della quota del ferro è diventato il nodo centrale anche delle successive proposte di PRG redatte dagli Uffici tecnici del Comune di Catania, nel 2004 e nel 2012, quest’ultima con la consulenza del Dipartimento di Architettura dell’Università degli Studi di Catania. Entrambe le proposte normano il tratto di costa, tra piazza Europa e piazza Giovanni XXIII, come “Area risorsa” fondata sul principio della perequazione [7].

Seppur con percentuali diverse [8], entrambe le proposte prevedono la realizzazione di un parco costiero lungo il tracciato ferroviario dismesso, con percorsi pedonali e ciclabili finalizzati alla fruizione del litorale da parte dei cittadini, la riconversione degli edifici dismessi di viale Africa e la realizzazione di nuove edificazioni lungo la fascia costiera, destinate a funzioni residenziali, commerciali, attività culturali, attrezzature alberghiere, servizi di interesse collettivo, uffici privati; accessi diretti, fisici e visivi con il fronte marittimo.

Altro obiettivo comune, fondamentale per lo sviluppo sostenibile dell’area, è il potenziamento del trasporto pubblico e la localizzazione, secondo il principio dei Transit-Oriented-Development (TOD) statunitensi (Calthorpe, 1993), un mix funzionale in corrispondenza dei nodi di trasporto pubblico su ferro esistenti e di progetto, e la realizzazione di un nodo di interscambio in piazza Giovanni XXIII, realizzato in corrispondenza di parcheggi scambiatori, delle stazioni metropolitane urbane e territoriali e dei terminal dei bus urbani ed extraurbani.

As already mentioned, the area has always been at the center of the city’s urban planning debate, ever since the choice of the site for the construction of the railroad, which gave a specific infrastructural layout to the area. However, the city is still waiting for a new General Urban Plan since, despite the succession of proposals over the past two decades, the General Regulatory Plan, drafted by architect Luigi Piccinato in 1964, and approved in 1969, still constitutes the current municipal urban planning instrument.

That plan merely circumscribes the strip between Africa Avenue and the de Larmisi cliff “Industrial-Portal-Railway Area,” identifying green areas without, however, giving specific definition to the interspaces surrounding the rail line. In addition, maximum land and resource exploitation is planned instead of reuse, redevelopment of the existing and recovery of the city’s relationship with the sea.

Subsequently, a number of procedures for variants and exceptions to the General Regulatory Plan were activated, including a City Council resolution in 1979 that included the former refineries, due to the relevance of their historical memory, among the areas subject to a Recovery Plan, and in 1989 the “Le Ciminiere” exhibition center, designed by architect Giacomo Leone, was built there. Today the center, which has an area of almost 25,000 square meters and is used as a multipurpose center (fair, exhibition and conference), is a cultural nerve center for the entire municipality, representing great potential for the entire area. In fact, it houses, among other things, a permanent museum on the 1943 landing in Sicily, various temporary exhibitions, fairs and congresses, and is also used for concerts, theater and film performances.

An early hint of the desire to redevelop and enhance the area along the de Larmisi cliff can be found in the 1994 General Regulatory Plan proposal, in which Pierluigi Cervellati, while maintaining the railroad track on the surface, manifests a desire to create a kind of waterfront, proposing an equipped quay over the tracks intended as a pedestrian area, directly accessible at certain points; the re-functionalization of the old locomotive depot; the redevelopment of abandoned buildings along Africa Avenue, intended for services of common interest; and the redefinition near Piazza Galatea, of green areas. However, architect Cervellati, rather than resolving the critical issues formulated, sticks to defining and interpreting the interspaces as result spaces, based on the railway infrastructure and what already exists.

The full recovery and fruition of the waterfront are nodal points of the proposal of Oriol Bohigas, of MBM Arquitects studio, author of Barcelona’s plan for the 1992 Olympics, commissioned in 2004 by the municipal administration for a preliminary design of the coastal strip between the commercial port and Ognina. The Spanish architect, following the preliminary design of the Italian Railway Network, chooses the burying of the railway line and station, in order to plan the territorial integrability of the coastal area and increase the usability of the urban space by citizens. Through the design of the waterfront, with new forms capable of restoring quality to the place, it envisages the re-functionalization of the railway warehouse and disused buildings, the construction of luxury tourist facilities, the tracing of a road along the coast, the extension of a transversal axis from Africa Avenue to the sea and the construction of an adjacent surface parking lot, as well as the construction of a marina north of the breakwater, the latter taken up by subsequent General Regulatory Plan proposals. Lacking, however, is an integrated project that contemplates intermodality within it, not favoring pedestrian viability in any case.

The lowering of the iron height also became the central issue in the subsequent General Regulatory Plan proposals drafted by the Technical Offices of the City of Catania, in 2004 and 2012, the latter with the advice of the Department of Architecture of the University of Catania. Both proposals regulate the stretch of coastline, between Piazza Europa and Piazza Giovanni XXIII, as a “Resource Area” based on the principle of equalization [7].

Although with different percentages [8], both proposals envisage the creation of a coastal park along the decommissioned railway track, with pedestrian and bicycle paths aimed at citizens’ enjoyment of the coastline, the conversion of the decommissioned buildings in Viale Africa and the construction of new buildings along the coastal strip, intended for residential functions, commercial, cultural activities, hotel equipment, services of collective interest, private offices; direct, physical and visual accesses with the waterfront.

Another common goal, fundamental to the sustainable development of the area, is the enhancement of public transport and the location, according to the principle of the U.S. Transit-Oriented-Development (TOD) (Calthorpe, 1993), a functional mix at existing and planned rail public transport nodes, and the realization of an interchange at John XXIII Square, built at park-and-ride parking lots, urban and territorial metropolitan stations, and urban and suburban bus terminals.

Possibili scenari futuri

Possible Future Scenarios

Come avvenuto nelle dinamiche e nelle recenti trasformazioni in ambito internazionale, che hanno dominato l’attenzione in termini di riqualificazione urbana, recupero, integrazione e opportunità di sviluppo, anche a Catania, negli ultimi anni, le richieste sempre più pressanti della città hanno determinato una forte attenzione sulla possibile riqualificazione del waterfront.

Da una attenta e critica disamina delle dinamiche urbanistiche della città, così come dall’analisi dei recenti progetti precedentemente esposti, si evince il ruolo fondamentale che l’infrastruttura ferroviaria ha avuto e che potrebbe avere in futuro.

La prospettiva di riconvertire l’area lungo la scogliera, a seguito dell’abbassamento del piano del ferro, dell’interramento della stazione ferroviaria e della dismissione del depósito delle locomotive (sebbene quest’ultimo intervento sia ancora da definire) sarebbe, indubbiamente, un’occasione unica per la creazione di un waterfront urbano, in un’area che, oltre alla rilevante valenza paesaggistica e ambientale, ha un elevato carattere strategico, per la prossimità con gli assi commerciali di Corso Italia e Viale Ionio e con il centro storico, la presenza del porto turistico Caito e del Centro Fieristico “Le Ciminiere”.

As has occurred in the dynamics and recent transformations in the international arena, which have dominated attention in terms of urban redevelopment, rehabilitation, integration, and development opportunities, in Catania, too, in recent years, the city’s increasingly pressing demands have led to a strong focus on the possible redevelopment of the waterfront.

A careful and critical examination of the city’s urban dynamics, as well as an analysis of the recent projects previously outlined, reveals the fundamental role that the railway infrastructure has played and may play in the future.

The prospect of redeveloping the area along the cliff, as a result of the lowering of the railroad grade, the burying of the train station, and the decommissioning of the locomotive warehouse (although the latter intervention has yet to be defined) would, undoubtedly, be a unique opportunity for the creation of an urban waterfront in an area that, in addition to its relevant landscape and environmental value, has a high strategic character, due to its proximity to the commercial axes of Corso Italia and Viale Ionio and to the historic center, the presence of the Caito tourist port and the “Le Ciminiere” Exhibition Center.

Aree interessate dall’infrastruttura ferroviaria. Al centro la Stazione Catania Centrale, a destra parte del polo fieristico Le Ciminiere e alcuni edifici dismessi lungo viale Africa.

Areas affected by the railway infrastructure. In the centre, Catania Central Station, on the right part of the Le Ciminiere exhibition center and finally some abandoned buildings along Viale Africa.

Anche i programmi di potenziamento del trasporto pubblico messi in atto da RFI e da Ferrovia Circumetnea per la linea metropolitana [9], che si pone come obiettivo il collegamento delle tratte esistenti con la fascia pedemontana etnea a nord-ovest della città e, lungo la periferia sud ovest, con l’infrastruttura aeroportuale, attraverso un’elevata accessibilità grazie ad un sistema di trasporto pubblico su ferro integrato, garantiranno ulteriore potenzialità di sviluppo e rivalutazione al tempo stesso.

Il recupero del litorale costiero de Larmisi potrebbe essere una grande risorsa per la città, per implementare nuove strategie di pianificazione, risolvere importanti criticità e inserire nuove funzioni richieste da tempo dalla città, nell’ottica di uno sviluppo sostenibile.

Infatti, gli interventi di demolizione e riorganizzazione del tessuto esistente, previsti dal PRG del 1969, non sono stati eseguiti né sono state espropriate le aree destinate a verde pubblico, con conseguente parziale realizzazione dei servizi.

Inoltre, a causa dell’attuale sistema della mobilità, cresciuto senza un piano predeterminato, si evince la scarsità, lungo il viale Africa e le vie limitrofe, di aree ad uso esclusivo della mobilità pedonale, oltre che la mancanza di percorsi ciclistici (Cocuzza et al., 2010). Indubbiamente, la riqualificazione del waterfront e delle aree circostanti deve passare attraverso anche scenari più sostenibili dal punto di vista della mobilità (Banister, 2008), in linea con le politiche dell’Unione Europea [10], potenziando l’accessibilità [11], favorendo la mobilità pedonale e ciclistica, la cosiddetta “mobilità dolce”, al fine di assicurare un’elevata efficienza spaziale ed energetica, benessere fisico, equità sociale [12] ed aumento della sicurezza stradale.

Tutto ciò in accordo con il valore emblematico che i waterfront hanno assunto, diventando spazi pubblici delle città, che si prolungano, senza soluzione di continuità, fino al mare. Il waterfront non è più limite fisico, confine o “linea” ma “rete di luoghi, intersezione di usi, funzioni e flussi” (Carta, 2012). Un’area strutturalmente complessa composta da sistemi spaziali interconnessi, esteticamente, funzionalmente e socialmente, con “funzioni produttive, relazionali, culturali, ludiche, abitative” (Carta, 2006).

Pertanto un obiettivo prioritario, per lo sviluppo del waterfront di Catania, è proporre nuove opportunità di crescita sostenibile grazie al conseguimento del recupero e della fruizione del patrimonio culturale e ambientale, favorendo l’integrabilità tra il tessuto urbano consolidato e il mare, attraverso la fruibilità della costa con accessi diretti, fisici e visivi; il recupero degli edifici dismessi presenti tra il viale Africa ed il sedime ferroviario, da destinare a nuove funzioni (ricettive, commerciali, direzionali e culturali) legate anche alla promozione del turismo (Cocuzza et al., 2010).

La riqualificazione passa anche attraverso progetti di grande qualità urbanistica e architettonica. Il waterfront dovrebbe essere ridisegnato con interventi fra loro integrati, con particolare attenzione alle possibili soluzioni, per indagare la variazione della linea di costa e la creazione di nuovi spazi per assolvere a nuove funzioni (ricettive, aree verdi, aree per lo sport, aree di sosta e ricreative) (Cocuzza et al., 2010). In tale ottica si pongono sia la recente proposta di Piano Regolatore Portuale che il progetto dell’Amministrazione Comunale, in corso di realizzazione, di una pista ciclabile lungo le l’arteria stradale che costeggia il porto da via Plebiscito al faro Biscari, costituita dalle vie Cristoforo Colombo e Domenico Tempio.

The public transport enhancement programs implemented by Italian Railway Network and Ferrovia Circumetnea for the metro line [9], which aims to connect the existing sections with the Etna foothills to the northwest of the city and, along the southwest suburbs, with the airport infrastructure, through high accessibility thanks to an integrated public rail transport system, will also ensure further potential for development and revaluation at the same time.

The redevelopment of the de Larmisi coastal shoreline could be a great resource for the city to implement new planning strategies, solve important critical issues, and incorporate new functions long demanded by the city with a view to sustainable development.

In fact, the demolition and reorganization of the existing fabric envisaged by the 1969 General Regulatory Plan has not been carried out, nor have the areas earmarked for public green space been expropriated, resulting in the partial implementation of services.

In addition, due to the current mobility system, which has grown without a predetermined plan, it is evident that there is a scarcity, along Africa Avenue and neighboring streets, of areas for the exclusive use of pedestrian mobility, as well as a lack of bicycle paths (Cocuzza et al., 2010).

Undoubtedly, the redevelopment of the waterfront and the surrounding areas must also go through more sustainable scenarios from the point of view of mobility (Banister, 2008), in line with European Union policies [10], enhancing accessibility [11], promoting pedestrian and bicycle mobility, so-called “soft mobility,” in order to ensure high spatial and energy efficiency, physical well-being, social equity [12] and increased road safety.

All this is in accordance with the emblematic value that waterfronts have taken on, becoming public spaces of cities, which extend, seamlessly, to the sea. The waterfront is no longer a physical limit, boundary or “line” but a “network of places, intersection of uses, functions and flows” (Carta, 2012). A structurally complex area composed of interconnected spatial systems, aesthetically, functionally and socially, with “productive, relational, cultural, recreational and housing functions” (Carta, 2006).

Therefore, a priority objective, for the development of Catania’s waterfront, is to propose new opportunities for sustainable growth through the achievement of the recovery and enjoyment of the cultural and environmental heritage, favoring the integrability between the consolidated urban fabric and the sea, through the usability of the coast with direct, physical and visual accesses; the recovery of disused buildings present between Africa Avenue and the railway embankment, to be allocated to new functions (receptive, commercial, directional and cultural) also related to the promotion of tourism (Cocuzza et al., 2010).

Redevelopment also passes through projects of great urban and architectural quality. The waterfront should be redesigned with interventions that are integrated with each other, with particular attention to possible solutions, to investigate the variation of the coastline and the creation of new spaces to fulfill new functions (receptive, green areas, areas for sports, rest and recreational areas) (Cocuzza et al., 2010). Both the recent Port Master Plan proposal and the Municipal Administration’s ongoing project for a bicycle path along the arterial road that runs along the harbor from Via Plebiscito to the Faro Biscari, consisting of Via Cristoforo Colombo and Via Domenico Tempio, are placed in this perspective.

Conclusioni

Conclusion

È indubbio che per la definizione del waterfront della città è necessario sia sciogliere il “Nodo Catania”, con l’interramento della linea ferroviaria e delle strutture ad essa connesse, che la realizzazione degli interventi previsti dal nuovo PRP. Da ciò ne deriva un ripensamento generale del fronte marittimo, come possibile motore di sviluppo sostenibile e rigenerazione urbana.

Occorre, dunque, procedere ad una trasformazione e valorizzazione delle aree ferroviarie e di quelle poste lungo i margini dello scalo; ad una ricomposizione morfologica e funzionale tra la città e la scogliera de Larmisi; indagare le potenzialità del contesto urbano circostante per assumere un ruolo di “nuova centralità” urbana.

Dalla disamina delle dinamiche urbanistiche e dei piani proposti susseguitesi negli anni, si evince che l’usuale approccio settoriale risulta essere ormai superato dalla necessità di una ricerca interdisciplinare, in grado di gestire meglio problemi più complessi.

Pertanto, sarà fondamentale la sinergia e il coordinamento tra tutti gli attori interessati per evitare un processo decisionale frammentato, in passato principale causa di trasformazione urbanistiche progettate e, spesso, non attuate.

Il coinvolgimento e coordinamento delle parti coinvolte è imprescindibile per ottenere un processo decisionale di pianificazione trasparente [13], arricchito dai contributi di tutte le categorie al fine di supportare decisioni condivise (Ignaccolo et al., 2013), necessarie per dare al waterfront un ruolo chiave di apertura di nuovi spazi, servizi e funzioni.

There is no doubt that for the definition of the city’s waterfront, it is necessary both to dissolve the “Catania Node,” with the burying of the railway line and related facilities, and the implementation of the interventions envisaged by the new PRP. From this follows a general rethinking of the waterfront as a possible driver of sustainable development and urban regeneration.

It is necessary, therefore, to proceed to a transformation and enhancement of the railway areas and those located along the margins of the port; to a morphological and functional recomposition between the city and the de Larmisi reef; to investigate the potential of the surrounding urban context to assume a role of urban “new centrality.”

Examination of the urban planning dynamics and proposed plans that have followed one another over the years shows that the usual sectoral approach appears to be outdated by the need for interdisciplinary research that can better handle more complex problems.

Therefore, synergy and coordination among all stakeholders will be crucial to avoid fragmented decision-making, which in the past has been the main cause of planned and, often, unimplemented urban transformation.

Stakeholder involvement and coordination is imperative to achieve a transparent planning decision-making process [13], enriched by input from all categories in order to support shared decisions (Ignaccolo et al., 2013), which are necessary to give the waterfront a key role in opening up new spaces, services and functions.

IMMAGINE INIZIALE | Vista panoramica del lungomare di Catania, con il tracciato ferroviario.

HEAD IMAGE | Panoramic view of the waterfront of Catania, with the railway track.

╝

NOTE

NOTES

Articolo pubblicato in PORTUSplus Journal n. 15 – 2015 e aggiornato dalle autrici nel 2024.

Cocuzza, Elena, and Eliana Fischer. 2015. “The Waterfront of Catania Between past and Future: The Larmisi Cliff”. PORTUSplus 5 (April).

https://portusplus.org/index.php/pp/article/view/141

[1] Società proprietaria dell’infrastruttura ferroviaria nazionale.

[2] Società gestore dell’infrastruttura ferroviaria nazionale.

[3] Approvato con delibera del CIPE, Comitato Interministeriale per la Programmazione Economica, n. 45 del 2004. Istituito nel 1967, il CIPE è un organo collegiale del Governo di decisione politica in ambito economico e finanziario che svolge funzioni di coordinamento in materia di programmazione della politica economica da perseguire a livello nazionale, comunitario ed internazionale.

[4] “Relazione Illustrativa generale del PRG di Catania”, redatta dal Comune di Catania nel 2004.

[5] Strumento legislativo che stabilisce procedure e modalità di finanziamento per la realizzazione delle grandi infrastrutture strategiche in Italia per il decennio dal 2002 al 2013.

[6] Le reti di trasporto trans-europee TEN-T, Trans European Networks-Transport, sono incentrate su 5 corridoi di trasporto multimodale che collegano i principali nodi urbani europei, con i principali porti marittimi e fluvio-marittimi, i principali aeroporti, i principali interporti o centri di scambio modale strada-ferrovia.

[7] Principio che prevede, a fronte delle previste urbanizzazioni, che i promotori dell’intervento cedano all’Amministrazione aree da destinare ad attrezzature pubbliche.

[8] La prima proposta prevede che il 50% dell’area sia destinato a verde pubblico e sport; il 40% a parco urbano ed il restante 10% a parcheggi; la seconda prevede, invece, la realizzazione di un parco costiero, di circa 15 ettari (Fonte: “Relazione Illustrativa generale del PRG di Catania”, redatta dal Comune di Catania nel 2004 e “PRG Catania. Relazione Generale”, redatto nel 2012).

[9] Attualmente la Ferrovia Circumetnea (FCE), in ambito urbano, offre un servizio di tipo metropolitano, nato come evoluzione del tratto Catania-Randazzo su tratte proprie. L’esercizio di tipo metropolitano ancora non sfrutta appieno la potenzialità della linea e dei mezzi, a causa dell’incompletezza della rete.

[10] Commissione Europea (2001), Libro bianco. La politica europea dei trasporti fino al 2010: il momento delle scelte; Commissione Europea (2007), Libro verde. Verso una nuova cultura della mobilità urbana; Commissione Europea (2011), Libro bianco. Tabella di marcia verso uno spazio unico europeo dei trasporti – Per una politica dei trasporti competitiva e sostenibile.

[11] Potenzialità di interazione tra diverse attività umane distribuite sul territorio. Tale approccio è più sostenibile rispetto a quello tradizionale orientato a favorire la mobilità, intesa come potenzialità di compiere spostamenti il più rápidamente possibile, per lo più con il mezzo privato, non considerando adeguatamente i conseguenti impatti.

[12] Possibilità per tutte le categorie sociali di muoversi utilizzando diverse modalità di trasporto.

[13] Attraverso lo scambio di informazioni e l’interazione tra le parti interessate e tra questi e il processo decisionale. È importante coinvolgere le parti interessate fin dall’inizio del processo di pianificazione, con diversi livelli di coinvolgimento nelle differenti fasi.

Article published in PORTUSplus Journal n. 15 – 2015 and updated by the authors in 2024.

Cocuzza, Elena, and Eliana Fischer. 2015. “The Waterfront of Catania Between past and Future: The Larmisi Cliff”. PORTUSplus 5 (April).

https://portusplus.org/index.php/pp/article/view/141

[1] Company that owns the national railway infrastructure.

[2] Italian Railway Network is the National railway infrastructure management company.

[3] Approved by resolution of CIPE, Interministerial Committee for Economic Planning, No. 45 of 2004. Established in 1967, the CIPE is a collegial body of the government for policy-making in the economic and financial spheres that performs coordinating functions in matters of economic policy planning to be pursued at the national, EU and international levels.

[4] “General Illustrative Report of the General Regulatory Plan of Catania,” prepared by the City of Catania in 2004.

[5] Legislative instrument establishing procedures and financing arrangements for the construction of major strategic infrastructure in Italy for the decade from 2002 to 2013.

[6] Trans-European Networks-Transport, TEN-T, are centered on 5 multimodal transport corridors that connect major European urban nodes, with major seaports and river-maritime ports, major airports, and major interports or road-rail modal interchange centers.

[7] Principle that, in return for the planned urbanization, the promoters of the intervention should give up to the Administration areas to be used for public facilities.

[8] The first proposal calls for 50 percent of the area to be used for public greenery and sports; 40 percent for an urban park and the remaining 10 percent for parking; while the second proposal calls for the creation of a coastal park, about 15 hectares in size (Source: “General Illustrative Report of the General Regulatory Plan of Catania,” prepared by the City of Catania in 2004 and ” General Regulatory Plan Catania. General Report,” prepared in 2012).

[9] Currently, the Ferrovia Circumetnea (FCE), in urban areas, offers a metropolitan-type service, which originated as an evolution of the Catania-Randazzo section on its own routes. The metropolitan-type operation still does not exploit the full potential of the line and vehicles, due to the incomplete network.

[10] European Commission (2001), White Paper. European transport policy to 2010: time for choices; European Commission (2007), Green Paper. Towards a new culture of urban mobility; European Commission (2011), White Paper. Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area – Towards a competitive and sustainable transport policy.

[11] Potential for interaction between different human activities distributed across the territory. This approach is more sustainable than the traditional one geared toward encouraging mobility, understood as the potential to make trips as quickly as possible, mostly by private vehicle, not adequately considering the resulting impacts.

[12] Ability for all social groups to move around using different modes of transportation.

[13] Through information exchange and interaction among and between stakeholders and the decision-making process. It is important to involve stakeholders from the very beginning of the planning process, with different levels of involvement at different stages.

RIFERIMENTI

REFERENCES

Bruttomesso R. (2007) Nuovi scenari urbani per le città d’acqua, Percorsi d’acqua.

Calthorpe P. (1993) The Next american metropolis, Princeton Architectural Press.

Carta M. (2006) “Waterfront di Palermo: un manifesto-progetto per la nuova città creative”, PORTUS n. 12, pp. 84-89.

Carta M. (2012) “Palermo waterfront: planning the “fluid city”, PORTUS n.24, pp. 88-95.

Cascetta E., Pagliara F. (2013) “Public Engagement for Planning and Designing Transportation Systems”, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 87, pp. 103-116.

Cocuzza E., Fischer E. (2010) Intermodalità, Paesaggio, Architettura tra la costa e la città di Catania, Tesi di Laurea in Architettura, Università degli Studi di Catania.

Ignaccolo M, Inturri G., Le Pira M. (2013) “The role of public participation in sustainable port planning”, PORTUS n. 26, November.

Dato G. (1983) La città di Catania: forma e struttura, 1693-1833, Officina Edizioni, pp. 16- 56.

De Luca V. (2012) “La città raffigurata e la città esistita. Il quartiere “Civita” a Catania”, Agorà n. 41, Editoriale Agorà, pp. 58-63.

Gabrielli B. (2004), “La rinascita delle città: il caso di Genova”, PORTUS n. 8, October, pp.42-45.

Rebecchini G., Caudullo F., Dato G., Lo Curzio M., Dantes L., Pirruccello C. (1991) Le vie dello zolfo in Sicilia: storia ed architettura, Officina edizioni, Roma.