Small but beautiful

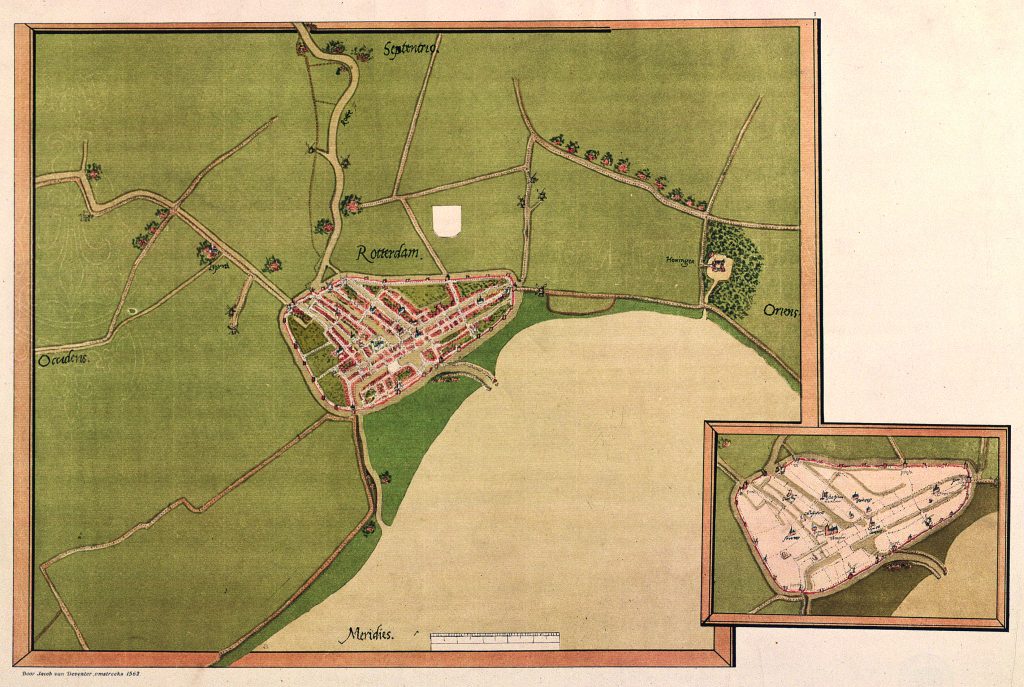

The fishing village of Rotterdam was founded in 1270 when the river Rotte, a peat stream from which the city took its name, was dammed. Seventy years later, the river town acquired city rights and privileges from the count of Holland. Visitors to Rotterdam will probably not realize immediately that it is a historical city. There is virtually nothing to remind us of this earliest period in its history, apart from the landscape that still features the medieval water structure and band of dikes that protected the inhabitants from flooding. For that matter, Rotterdam at that time was of little significance and for a long time overshadowed by other towns and cities in the region, such as Delft and Dordrecht, that were older, richer, and more influential.

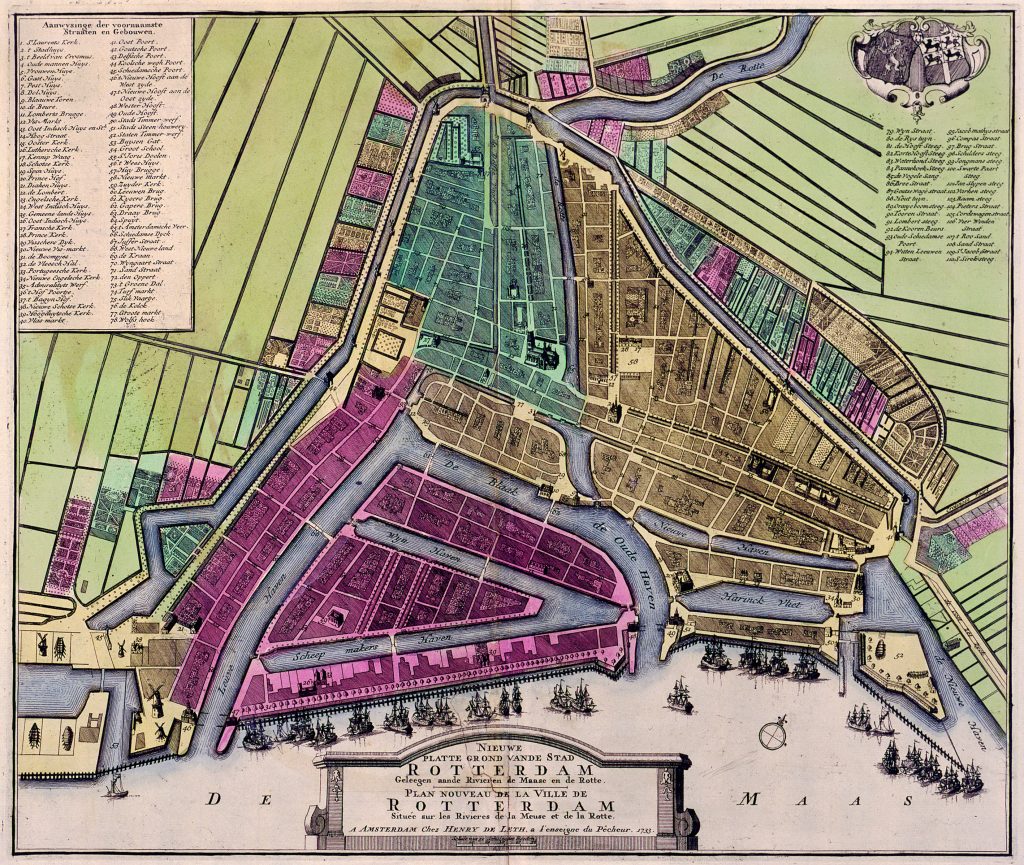

The herring trade pushed Rotterdam’s advance as a commercial city only around 1550. Herring as a commodity turned out to be perfectly suited to domestic and foreign wholesale trade with the Rhine and Scheldt regions and with France. Ships that travelled to these regions brought cargoes back with them, which boosted Rotterdam’s position as an international entrepot. In Rotterdam, the herring made a series of other economic activities easier to achieve and laid the foundations for its huge success as an international trading centre. At the end of the sixteenth century, Rotterdam also took advantage of new trading opportunities as the Netherlands started to dominate the global financial, trade and colonial markets. Rotterdam merchants mainly emphasised trade with the west: France, England, and Scotland. The wine trade with southwest France became substantial: in 1618, the town council considered this trade to be the town’s primary one. In less than half a century, Rotterdam had ascended to the rank of the Republic’s second merchant city after the impressive and much larger and richer Amsterdam. The unruly growth of the urban area in the seventeenth century was a reaction to this sharp increase in trading and shipping activities and led to the building of the Waterstad (Watertown). This port-city expansion gave Rotterdam its characteristic triangular shape that would define the urban landscape, port-city relationships and also urban planning policies until 1850.

The transitpolis of the Rhine Delta

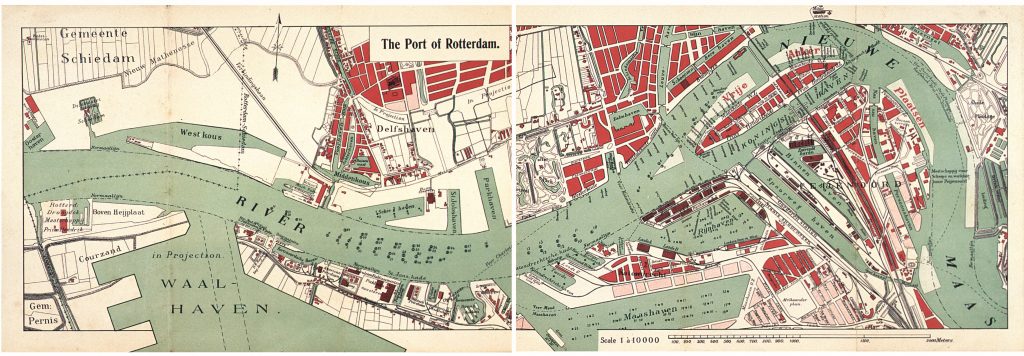

Over the nineteenth century, Rotterdam would break through as a major international port city. Changes in the organization of trade and transport, the shift from sailing ships to steamships, and a new international geo-political order dominated by Britain and Prussia challenged the Rotterdam business community between 1830 and 1870. From 1870 the town was rapidly modernised, the effects of which were most clearly visible in the expansion of the harbour landscape on the southern bank of the Maas opposite the old town centre. Rotterdam profited from its natural location on the Rhine and was able to exploit this position through the construction of the Nieuwe Waterweg, the connection to the North Sea which began a new stage in the port city’s development and unprecedented economic growth. The transformation started with the area of Feyenoord across the river Maas and from the mid-eighties’ onward, river docks like Rijnhaven, Maashaven and Waalhaven (Rhine, Meuse and Waal docks) were developed that reshaped the river landscape south of Rotterdam. The river – ‘wet’ – docks were based on the concept of large water basins: huge docks easily accessible to sea-going ships, where ships moored to buoys could be loaded and unloaded ‘midstream’, from or into inland vessels moored alongside. Before the First World War Rotterdam celebrated its port’s successes.

In 1913 the tonnage transmitted by Rotterdam to Germany was almost eight times higher than in 1890. It had risen from about 2 million tons to 16 million tons, with an average annual growth rate of 9%. Rhine barges carried to the hinterland steel, iron, cereals, and oil, which accounted for approximately 74% of total transit trade. The annual growth rate for transhipment from Germany to Rotterdam was about 13%, from half a million to 7 million tons in the same period. Coal was the major bulk good sent to Rotterdam. Initially, the city did not have a very strong position in oil-transhipment, but its successful transformation into a transit port also made it a place of interest for transnational oil firms entering the European market selling new products. After 1918, however, the city was forced to rethink the economics of its port. The Rhine economy had almost collapsed and the city government hoped to reduce dependence on the German hinterland. Leading business officials, politicians and the Chamber of Commerce tried to increase the industrial output of the Rotterdam region. However, the region was not successful in attracting non-maritime related industries other than the petroleum business. The restructuring of the oil industry also impacted port-city relations, and this would continue after the Second World War.

The port city region of oil

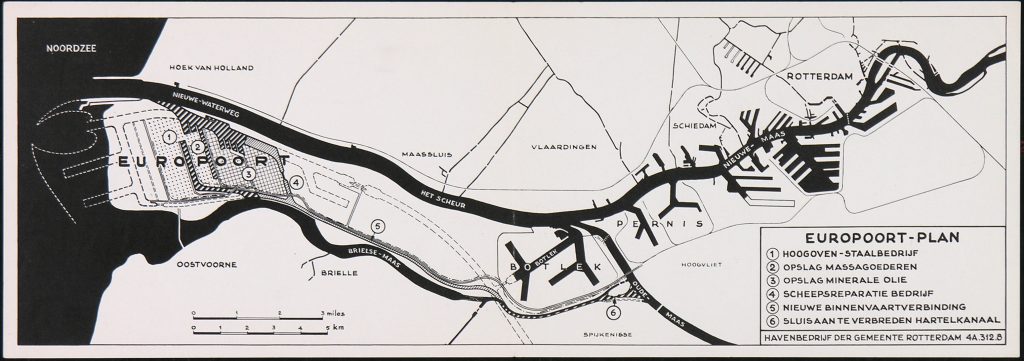

The bombardment of Rotterdam on May 14th in 1940, which reduced large sections of the city to rubble, forced its inhabitants to build a new city. It became clear soon after the flames had been extinguished and work began on clearing the debris that pre-war Rotterdam would not be rebuilt. Rotterdam would rise as a new city, planned in accordance with the latest insights in modernism, architecture, and urban planning. After 1945 the city gave priority to the restoration of the harbour, which was destroyed by the Germans in September 1944, rather than to rebuilding of the city centre.

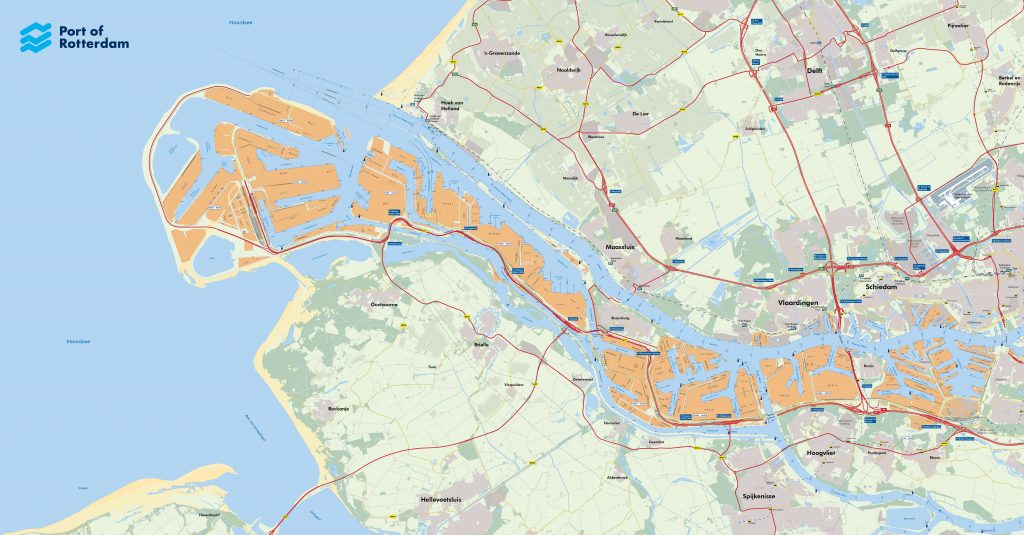

After 1945, Rotterdam developed an industrial port cityscape that created a city without a port. In 1947 the time was considered ripe for the development of the Botlek, but the development went much slower than expected. The expansion of Rotterdam was made possible by the rapid growth in international trade, especially in oil and oil products. The multinational oil companies no longer wanted to transport the crude oil to the hinterland by tanker along the Rhine, but through a pipeline to the Ruhr area and this idea led to merging the Botlek plan with that of Europoort (1957) into one single gigantic harbour area stretching from the sea to the Oude Maas. Europoort would procure Rotterdam the position of gateway to Europe and consisted of five petroleum docks, two general cargo and two bulk docks. It would increase the port area to 25,000 (10.000 hectares) acres in size, fifty times bigger than in 1880. The city was convinced that heavy industries were the basis of a mature urban economy. The eye-catching part of the plan was the Maasvlakte where the largest industrial firms, especially the future steel works of Rotterdam, would be installed.

In 1960 the first tanker entered the provisional new sea mouth of Rotterdam. Two years later Rotterdam celebrated the fact that it had become the biggest port in the world. Europoort was still under construction but at that time more than 100 million tons had already been distributed to the hinterland of Europe. Oil had become the most important bulk good. In 1963 the share of oil shipped to Rotterdam had increased to 58%, and since a major part of it was transhipped to the German hinterland, the port still depended on the growth potentials of the Ruhr-area.

After 1970, however, Rotterdam lost its primacy as the economic engine of the Netherlands. Once the proud city of the post-war era, Rotterdam became a place of distress, a reputation it shared with other European ports. It remained an important port, thanks to the oil and petrochemical industries. However, the port’s noise, pollution, and other environmental problems have strained the relationship with the city.

A city in doubt

Because of the economic depression, Rotterdam witnessed a severe set-back in trade and goods distributed through the gateway of Europe. Between 1950 and 1973, the annual average growth rate had been 9.5%. Just before the oil crisis Rotterdam handled 300 million tons of bulk and general cargo. In the early sixties it had won the ‘battle of the bulk’ and the city hoped to benefit from containers and wanted one of the European container ports, from where feeder ships could carry the containers to smaller European ports. In 1965 the first containers arrived and in the following year the E.C.T. (European Container Terminus; in 1989 reorganised in Europe Container Terminals) was established. This partnership of Rotterdam stevedore companies, Dutch Railways and Nedlloyd was stimulated by the new challenge of container technology. The Maasvlakte, once designed as an industrial outpost, was transformed into a high-tech service centre, where the largest European bulk transhipment and container centre would be in the eighties.

The major post-war harbour development outside the centre meant Rotterdam became a city without a working port. By the nineteen-seventies, the romantic, steam-whistling, and aromatic harbour with the transatlantic ships of the Holland-America Line was a thing of the past. Many of the docks that had been constructed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for transhipment lost their original purpose. The Kop van Zuid (Head of South, named after the nineteenth century port development on the south bank) became the first part of an extensive waterfront regeneration programme that went hand in hand with a new post-modern skyline, accentuating the new image of a world port city. The Erasmus Bridge, not simply a bridge but a symbol of the cultural élan of the early nineties, would link maritime heritage across the river with the inner-city redevelopment. The New York Hotel, the former head office of the Holland-America Line, became the first landmark of a re-imagined port city, Manhattan at the Maas.

New port city futures

The construction of the Second Maasvlakte (2008-2012) was the first new major expansion of the port since the 1970s. 2000 hectares of newly created land allowed the port of Rotterdam the possibility of doubling the transhipment of containers. Rotterdam’s Port Authority and the maritime business lobby-groups, supported by the city government, defended Rotterdam’s newest port expansion because of the new jobs it would create. However, the sophisticated, high-tech, and capital-intensive container terminals would generate less job opportunities, particularly for less-qualified workers. In this respect, since the 1970s the port economy has been losing its importance as a job engine.

The Second Maasvlakte is in fact an extension of the port-philosophy that depended on the Rhine-transit model, that had been developed 150 years ago. Containers became the new growth factor, instead of oil, but even though containers are looked upon as part of the emerging global network of the 1990s, the container business has not changed Rotterdam’s dependence on the Rhine. Since the Port of Rotterdam published its vision document in 2011 the world has changed rapidly, because of geo-political, social, technological and climate change impacts. This will be the major challenge for Rotterdam since the port’s regime is still based on scale and volume and its success is measured in throughput. New port scenarios are aimed at safeguarding Rotterdam’s future position as a major port and Europe’s most sophisticated energy hub. In order to do that, the port city region of Rotterdam has to develop an imaginative and creative vision which is intimately connected to that of its surrounding region. The fixation on growth will make it difficult to break path-dependencies and revise existing economic policies. New imaginative scenarios accordingly need to be developed. Softer values of society, cultural or ecological or community-driven strategies, with an unbiased approach to port city futures’ development, including designing for serendipity, unplanned or unexpected outcomes. Perhaps Rotterdam smart port will mean, eventually, a smaller port.

Head Image | View of the Boompjes and the Maas from a room in the Victoria Hotel on Willemsplein, a favourite location for many painters. From there you had a magnificent view on the working port that was still part of the city. Painting by Jacob Nieweg, 1931. (Source: Collection Museum Rotterdam).

References

Hein, Carola & Paul van de Laar (2020), “The Separation of Ports from Cities: The Case of Rotterdam”, in: A. Carpenter and R. Lozano (eds.), European Port Cities in Transition, Strategies for Sustainability, Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36464-9_15 265-286.

Van de Laar, Paul (2000), Stad van formaat. Geschiedenis van Rotterdam in de negentiende en twintigste eeuw [City of Size. The History of Rotterdam in the nineteenth and twentieth century] (Waanders Uitgeverij Zwolle 2000).

Van de Laar, Paul (2001), “The Port of Rotterdam in a changing environment. From Rhine port to Main Port: 1870-1970” in: Jaap R. Bruijn et. al. Eds. Strategy and response in the twentieth century and maritime world. Papers presented to the Fourth British-Dutch Maritime History Conference, Batavian Lion International for the Institute for Maritime History, Royal Netherlands Navy, Amsterdam 147-162.

Van de Laar, Paul & Van Jaarsveld, Mies (2007), Historical Atlas of Rotterdam. The city’s growth illustrated, Sun, Nijmegen.

Van de Laar, Paul (2021), De kleine geschiedenis van Rotterdam [The little history of Rotterdam], Thoth Bussum.