╔

The Bay Area is no stranger to technology and innovation-driven development, with Silicon Valley still accounting for one third venture capital investment in the US [1]. However, the moment of garage startups in single family homes and suburban tech giants (such as Apple’s Infinite Loop) that peaked in the mid-late 20th century appears to be coming to an end. Since 2008, a city like San Francisco (and other areas now considered more ‘urban’ due to their density such as Oakland and Emeryville) has seen enormous growth in tech companies, with tech employment rising by nearly 90% between 2010 and 2014, greatly surpassing Silicon Valley’s 30% [2]. Despite the fleeing of financial centers and large companies, San Francisco’s older and smaller office spaces and old industrial sites had continued to offer a productive habitat for smaller, more flexible startups. Now, it is the tech giants—whose only traces in the city thus far were skyrocketing housing prices, soaring inequality, and Wi-Fi-equipped buses with leather seats to drive tech-workers to Palo Alto—that appear to be considering their re-urbanization. And one of the key spaces for the taking, in a bay known for its Black-worker-fueled shipyard industry during WWII, are its ports.

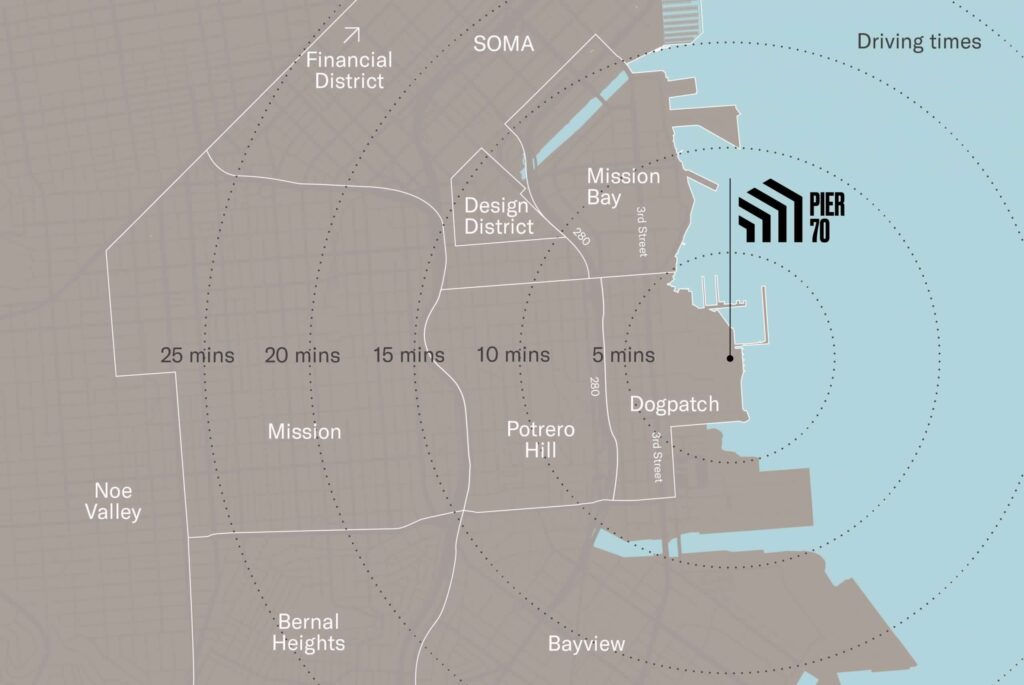

Map showing the location of Pier 70, driving time radiuses, and adjacent districts including Mission Bay. Image included in http://Pier70sf.com/.

The Pier 70 area circa 1918, looking north. Image by the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command. (Photo: public domain).

One example of this type of development is Pier 70, in San Francisco’s east coast, presented since its inception in 2008 as “a place that puts creativity at the center, is open and inviting to all and which brings people closer to the Bay [by including] one of the largest and most exciting Bay Area office and lab projects with 1.82M RSF of new office and R&D space opportunities” [3]. But this strategy of re-urbanizing big tech companies is being assayed beyond Pier 70: In 2003, thanks to the University of California-San Francisco’s biotechnology campus moving to Mission Bay, the area (immediately north of Pier 70) already developed as a de-facto waterfront innovation hub. And so has Hunter’s Point Shipyard, an area immediately south of Pier 70 adjacent to a shrinking Black working class neighborhood whose redevelopment plan also highlights innovation as part of their design. And, in recent years, these strategies have expanded beyond San Francisco and its waterfront areas. In 2011, for example, San Francisco’s Mayor Ed Lee already announced the aim to capitalize on already occurring tech-oriented growth South of Market Area (a downtown area known as SOMA) into the Mid-Market District, a zone of high racial inequalities and homelessness that had seen very uneven gentrification. And it is transforming areas across into the East Bay, with plans for the redevelopment of West Oakland—yet another historically redlined Black working class neighborhood.

The goals of innovation districts such as Pier 70 are quite explicit: The development of “an epicenter of creativity where art, making and innovation can thrive [with] a new waterfront cultural arts center, events programming [and] cultural experiences that inspire.” A space whose “soul” are to be “entrepreneurs defined by a spirit of experimentation and the open exchange of ideas” that can only happen in this “springboard for a vibrant creative ecosystem [made of] cafes, restaurants, and neighborhood retail, [p]edestrian friendly streets and nine acres of parks” [4]. Spaces like Pier 70 are to be, in short, the reversal of the logic of busing tech workers from San Francisco to the suburban South Bay, switching instead to bringing companies themselves to the city to capitalize on those urban values that made it an attractive place to their workers in the first place.

Rendering showing those urban values that new tech companies are trying to capitalize on via their re-urbanization. Image included in http://Pier70sf.com/.

These ideas, however, are not new. Already in 1961 the journalist and writer Jane Jacobs argued, in her defense of city life before the US phenomenon known as ‘white flight’ (the suburbanization of upper and middle-class American whites), for urban crossings, corners, and coffee-shops as spaces of innovation [5]. As spaces where ideas spark, and economic ventures begin. As places where the built environment and ‘the social’ meet in potentially productive yet non-deterministic ways—something that US planners forgot for decades with their highly aspatial and unimaginative zoning practices.

And yet, this is not 1961. And Jane Jacobs’ celebration of city space as a place of creativity and diversity that nonetheless requires “eyes on the street,” without a single Black American to be found in her brilliant prose, has been widely brought to question [6]. And so the problem remains: Whose creativity and whose diversity, and for whom?

Rendering showing imagined street life and the (re)use of industrial architectonic features as an urban value. Image included in www.brookfieldproperties.com/.

Spaces such as Pier 70 indeed include affordable housing (30% of the overall housing development) and low-skilled jobs in the service industry (listed in the Pier 70’s website as “purveyors of food and wine, brewers, butchers and makers of artisan goods” [7]). And, unlike their suburban predecessors, they emphasize diversity as an asset—after all, it’s that same diversity that brought half their workforce to seek life in urban areas and not in suburban developments in the South Bay. However, this emphasis on public space cultures entails a highly curated space, with a highly curated idea of diversity that must be ‘productive.’ In this context, public space and the organization of social life are no longer about the reproduction of labor power, as Marxist thinkers would have it. They are about the actual production of privately-owned public values and their associated surpluses. And this is to be achieved not just by capturing the rent gap in decaying industrial areas (as classical gentrification theories explain [8]) but rather, as the geographer John Stehlin argues, by urbanizing the very shopfloor into city-space and coopting the resulting creativity [9].

The logic of these spaces is thus to foster exchanges, creativity, and after hours work in a casual public setting while bypassing the risks and investment traditionally associated with either urban redevelopment or enclosure. Spaces like Pier 70, for instance, with the passing of Proposition D in 2008, are funded by capturing 75% of projected payroll taxes and hotel taxes for the yet-to-be Pier [10]. This means that the city assumes the risk of anticipating money that has not yet been collected under the promise of Pier 70’s success, cutting the City’s General Fund otherwise needed to provide city services (such as transit) in the Pier area and beyond.

Furthermore, their vision of public space emphasizes “parks and open spaces” and the construction of “a vibrant neighborhood [that] retains the texture and grit of the site’s industrial past (…) prioritize[ing] a pedestrian and bicycle friendly experience to support interaction and close community, while leveraging the area’s high level of accessibility” [11]. It emphasizes what the urban historian Margaret Crawford has called ‘feel good’ spaces—bar terraces with umbrellas, bike lanes, dog parks, and the like—that speak to one type of public (overwhelmingly upper class, and overwhelmingly white) but masks as universal [12]. Which is to say that this strategy assumes as self-evident, ‘good’ public spaces those spaces that folks in the tech industry—a White and Asian, male-dominated industry, as is widely known—will value as an asset and will find encouraging to network and work afterhours.

Images showing what urban historian Margaret Crawford has called “feel good spaces” (i.e. spaces that are designed with a universal subject in mind following a rhetoric of all-inclusivity). Images from: http://Pier70sf.com/ and www.brookfieldproperties.com/.

The true innovation of these spaces, then, is not so much the recognition that the ‘commons’ of public space (street corners and cafes, benches, parks, and bars) offer the necessary conditions for ideas and creativity to spark—something identified by Jacobs already in 1961. The true innovation of these spaces consists in the cooptation of these ‘commons’ (funded through public money and with a clear client in mind, even if masked as diversity) for private gain. It consists in fostering a highly curated form of diversity and public space cultures designed with the explicit goal of fostering privately-owned ideas.

The recuperation of waterfronts that are currently underused and inaccessible may be a good (and rather self-evident) idea, as is incorporating affordable housing, certain forms of retail, parks, and transportation. And locating innovation districts in port areas may indeed be less immediately damaging than when these same models are applied to central downtown areas such as Mid-Market District, where notions of ‘underused,’ ‘underutilized,’ and ‘run-down’ are quite literally obliterating the many folks and activities that inhabit those spaces in ways that are deemed ‘unworthy’ or ‘unproductive’.

However, the fact that the area of Hunters Point Blvd/Innes Ave (a traditionally Black, working class neighborhood adjacent to the already built waterfront innovation areas of Mission Bay and Hunter’s Point Shipyard) is the most segregated Black neighborhood in San Francisco [13] points precisely at the fact that this narrative of diversity, inclusion, and innovation through beautiful public spaces may in fact be masking the further exacerbation of inequalities in the already highly inequal Bay Area, even in the case of waterfront innovation districts. Thus, even if placing innovation districts in decaying industrial port areas may appear as a better choice than the redesign of downtown areas such as Mid-Market, their effects may indeed be just as far-reaching.

Most importantly, as a strategy of city-building, these new types of urban innovation districts seem to entail the willful abandonment of public space as space of tensions for a highly curated one geared towards production. And they entail the editing out of diversity in the very name of that same diversity—to be publicly funded yet capitalized on by a few tech giants. Funnily enough, as Stehlin suggests, it is probably on the private soil of smaller coworking spaces and socially engaged businesses that a true ‘commons’ of diversity and innovation may be taking place, from downtown Oakland to San Francisco itself. The question that remains for planners and designers, then, is to rethink what is exactly public here about public space.

HEAD IMAGE | Rendering of “One of the largest and most exciting Bay Area office and lab projects with 1.82M RSF of new office and R&D space opportunities. (Image included in http://Pier70sf.com).

╝

NOTES

[1] Data from Joint Venture Silicon Valley, and Institute for Regional Studies. 2022. “Silicon Valley Index”. Silicon Valley.

[2] Data from the California Employment Development Department Labor Market Information Division, 2015, quoted in Stehlin, John (2016), “The Post-Industrial ‘Shop Floor’: Emerging Forms of Gentrification in San Francisco’s Innovation Economy”, Antipode 48 (2): 474–93.

[3] “Pier 70”, Accessed April 15, 2023. https://pier70sf.com/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Jacobs, Jane (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities, especially “Chapter 7: The Generators of Diversity”, Modern Library ed. New York: Modern Library.

[6] See, for example, Bratishenko, Lev (2013), “Jane Jacobs’s Tunnel Vision”, Literary Review of Canada (blog). Accessed April 16, 2023. https://reviewcanada.ca/magazine/2016/10/jane-jacobss-tunnel-vision/.

[7] “Pier 70”, Accessed April 15, 2023. https://pier70sf.com/.

[8] Smith, Neil (1987), “Gentrification and the Rent Gap”, Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77 (3): 462–65.

[9] Stehlin, John (2016), “The Post-Industrial ‘Shop Floor’: Emerging Forms of Gentrification in San Francisco’s Innovation Economy”. Antipode 48 (2): 474–93.

[10] Legislative Digest (7/16/2008), “Pier 70 plan and lease approvals; General Fund financing for Pier 70 waterfront improvements; transfer of funds according to agreements between the Port Commission and other departments; priorities for use of Port funds”. https://sfelections.sfgov.org/. For commentators on the political debates around Proposition D see, for example, SPUR news (2008), “Proposition D – Pier 70 Financing and Planning – Voter guide”. https://www.spur.org/publications/voter-guide/2008-11-01/proposition-d-pier-70-financing-and-planning/.

[11] “Pier 70”, Accessed April 15, 2023. https://pier70sf.com/.

[12] Crawford, Margaret (2015), From the “Feel Good” City to the Just City. https://designactivism.be.uw.edu/from-the-feel-good-city-to-the-just-city/.

[13] Data provided by UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute in their 2020 Census Update, available in Menedian, Stephen, Samir Ghambir, and Chih-Wei Hsu (2021), “The Most Segregated Cities and Neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay”, Accessed April 15, 2023. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/most-segregated-cities-bay-area-2020/.

REFERENCES

Bratishenko, Lev (2010), “Jane Jacobs’s Tunnel Vision,” in Literary Review of Canada. Accessed April 16, 2023. https://reviewcanada.ca/magazine/2016/10/jane-jacobss-tunnel-vision/.

Crawford, Margaret (2015), From the “Feel Good” City to the Just City. https://designactivism.be.uw.edu/from-the-feel-good-city-to-the-just-city/.

Jacobs, Jane (1961), The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Modern Library ed. New York: Modern Library.

Joint Venture Silicon Valley, and Institute for Regional Studies (2022), “Silicon Valley Index”, Silicon Valley.

Legislative Digest (7/16/2008), “Pier 70 plan and lease approvals; General Fund financing for Pier 70 waterfront improvements; transfer of funds according to agreements between the Port Commission and other departments; priorities for use of Port funds”. https://sfelections.sfgov.org/.

Menedian, Stephen, Samir Ghambir, and Chih-Wei Hsu (2021), “The Most Segregated Cities and Neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay”, UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute, Accessed April 15, 2023. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/most-segregated-cities-bay-area-2020.

“Pier 70,” Accessed April 15, 2023. https://pier70sf.com/.

Smith, Neil. 1987. “Gentrification and the Rent Gap”. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77 (3): 462–65.

Stehlin, John. 2016. “The Post-Industrial ‘Shop Floor’: Emerging Forms of Gentrification in San Francisco’s Innovation Economy”. Antipode 48 (2): 474–93.