In Inhabited by 3 million people and 4 million with its surroundings, at first sight Casablanca might seem an international and cosmopolitan metropolis. However, after closer experience, Casa (as friendly nicknamed by her inhabitants), reveals to be a city tightly locked to her Berber origins in a paradox of nomad urbanism.

The population of “free people” (as, in fact, the etymologic meaning of the word “Berber” suggests) continues to maintain customs and traditions of North-African nomads. In the most ancient Medina, surrounded by high wall in red raw ground, the white buildings, from which the city took her name from, create a labyrinth of streets and dead-ends animated with full life where everything lives the happening present.

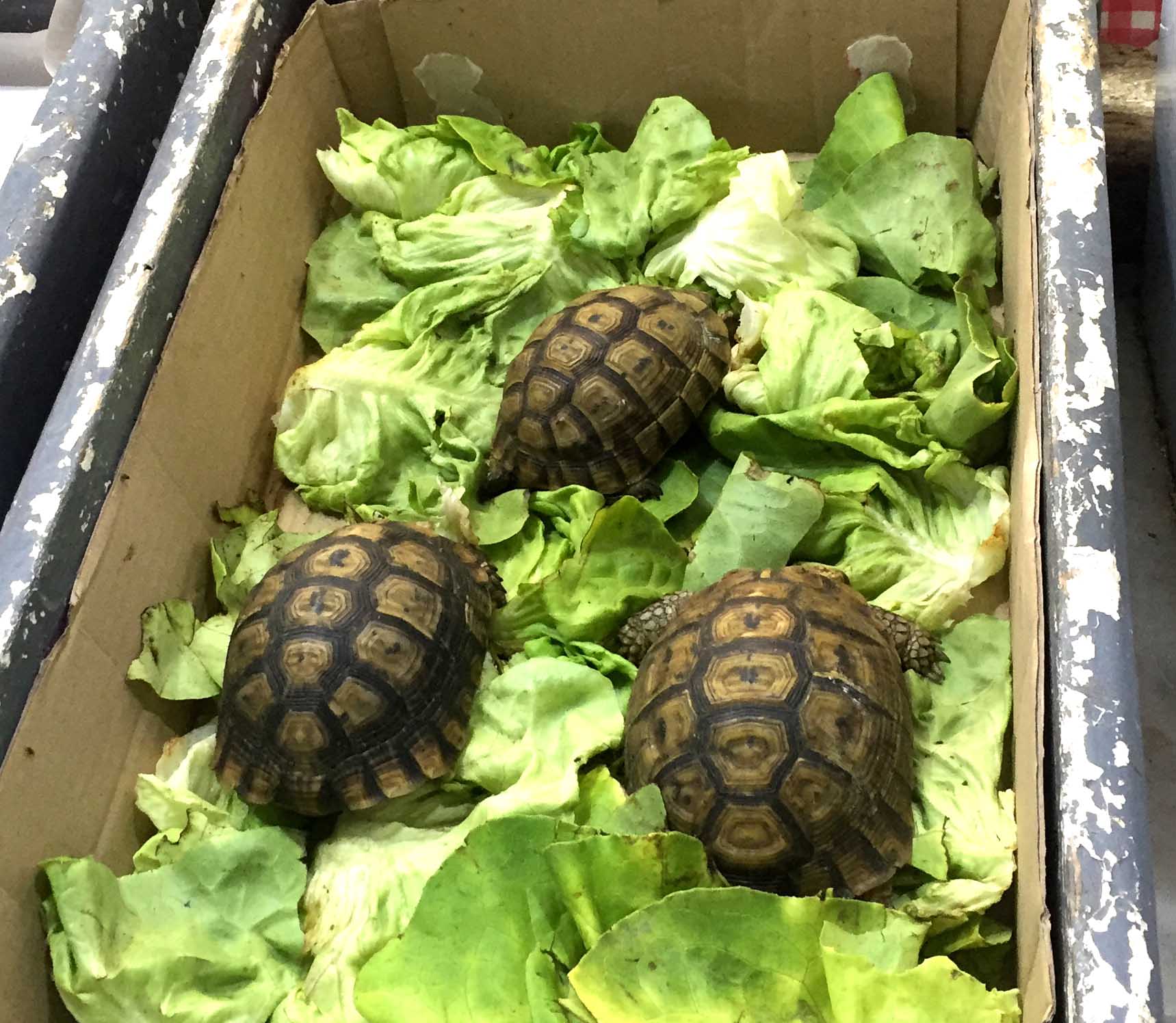

The Medina does not have a suq: the Medina IS the suq. Every corner is characterized by commercial activities for the sale of fruits and vegetables, clothes and shoes, meats and poultry … slaughtered or not ! (you might easily find live chickens on sale and even turtles crunching lettuce while waiting their destination …).

Marche central. Live turtles on sale in the covered fish market of Casablanca.

In here, you do not necessarily need a shop to have a commercial activity: all you need is a carpet laying on the floor to improvise a stand of vegetables (not exactly perfect, but today bio and zero kilometres are very fashionable!). A couple of sewing machines nicely placed along the street represent a tailoring shop; plastic stools and beach umbrellas are enough to pop up the dining room of an outdoor “restaurant” where the kitchen is a simple trolley on wheels equipped with burning coals and grill.

Carpet for the sale of vegetables in the Medina of Casablanca.

Tailors working in the streets of Casablanca’s Medina.

Street food and temporary dining stands in the Medina of Casablanca.

Street food is undoubtedly the main leading actor of Casablanca’s urban landscape; it’s presented in a huge variety of stands, all super functional in terms of mounting/dismounting, time of production and use of local products. Very popular in summer, also due to the hot and dry climate, are seasonal fruits such as prickly pears, pineapple and coconut, peeled and portioned at the time of sale; the juices of the vanilla orange, the Fès lemons and the sugar canes, extracted directly in front of the customer, are also very appreciated.

Stand of fresh fruit in the Medina of Casablanca. Oranges and lemon are squeezed with a traditional squeezer. Sugar cane is extracted with a dedicated electric extractor: the cane is inserted in a hole, from the beak at the other end the sugar juice is collected in a glass while the waste comes out from a third hole.

Shua (the Moroccan barbecue) is the king of street food: fish and lamb, beef, poultry and rabbit, marinated with cumin, coriander, turmeric, saffron and pepper fill the air with their scent. Smoke from the grill attracts many customers. As in the oldest Maghreb tradition, grilled dishes are served in the batbout, the traditional flat bread, used as a utensil. No need for plates or cutlery, just use your hands (actually, only the right hand because the left hand is considered impure …. Sorry, left-handed!). Bread is used as a case for containing meat, contours, trimmings. This practice allows incredible savings in terms of production and transport of kitchen furnishings that for a nomad society, always on the go, represents one of the major obstacles to face frequent travelling.

Barbeque at dine hours. Sausages and onions, garnished with spicy sauce, spices and fresh coriander are served inside a flat bread used as pouch, all served with French fires.

So every day, at lunch and dinner time, the Medina suddenly becomes populated with improvised street food banquets. But it’s the Casablanca waterfront, the Corniche Ain Diab overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, the true protagonist of a collective ritual that all sunsets is celebrated.

When King Hassan II decided where to build the new Mosque, one of the largest in the world and now a symbol of Morocco, he deliberately chose something out of the ordinary: rather than building it inside the city, he wanted to place it in the boundless horizon of ‘Atlantic Ocean, standing on the sunset of the western end of the continent, thus paying homage to the Maghreb, etymologically le lieu où le soleil se couche.

Resting on a rocky promontory on the sea and built for two thirds on ingenious reinforced concrete substructures, the building is in full communion with the elements of nature: the glass floor lets you enjoy the waves of the sea during prayer; the sliding ceiling welcomes the sky in its immensity; the foundations stretch out like roots in the rock. Every evening this powerful landmark offers one of the most extraordinary shows that the work of man has been able to create together with nature: the sun setting over the sea, tinting the horizon with its fiery rays, reverberates its light on the marble surfaces of the building and on the bright green, white and ocher zellige of the minaret, the highest in the world.

At the appointment with the sunset participates a heterogeneous multitude of people who gather on the vast square in front of the Mosque and along the Parc Sindibad, the park on the seafront that has enhanced the waterfront with efficient and elegant interventions of recovery and street furniture. Around the Mosque, rather than celebrating a religious function, a rite of passage from day to night that has neither nationality nor religious or ideological boundaries is shared spontaneously and peacefully.

The feeling experienced by each one, in his intimate, is different, but is united by a sense of harmony with nature and the world. Young people express it by diving from the top of the protective walls of the Mosque into the icy waves of the Atlantic, competing with each other for those who arrive farther. Groups of boys improvise a bit of music with drums and tambourines, singing the traditional question and answer songs of the ancient Berber tribes. The merchants are ready to add, to this moment of intimacy with nature, the pleasure of the palate.

Boys diving into the ocean from the walls of the Hassan II Mosque.

As the Maghreb tradition teaches, you don’t need a restaurant to feed a crowd; shacks, carts, trays carried on shoulder appear at the most opportune moment to offer the crowd every kind of comfort food, in accordance with the seasons and the portability of food.

Street vendor on the Casablanca waterfront next to the Hassan II Mosque.

In summer snails triumph, served in unmatched tea cups along with the cooking liquid to be sipped at the end; the cobs sizzle on the embers that give the beans an irresistible smoky taste; the sliced potatoes are fried in tempting spiral shapes; many people crunch nuts and peanuts while sipping the ever-present mint tea served hot and very sweet in small glasses.

Venditore ambulante di lumache accanto alla Moschea di Hassan II. Le lumache bollite vengono servite dentro tazze da tè insieme al liquido di cottura.

The sunset at the Great Mosque is the ideal habitat where briouates are propagated: this is a typical Moroccan preparation perfect to be consumed quickly and outdoors thanks to its small size. Inside a crispy shell of dough, wrapped in a triangle or a cylinder and fried so as not to miss anything from the filling, you can taste a delicious spiced stuffing with meat, fish, cheese or vegetable variations. A recent contamination with ingredients from other kitchens of the world has brought rice noodles to the filling of briouates; in this way, the far west meets the far east for the creation of one of the most successful street food in the world.

Briouates a forma di triangolo e di cilindro ripieni di spaghetti di riso, spezie e pesce, serviti con carote sottaceto e olive, in vendita accanto alla Moschea di Hassan II.

At the end of the sunset, and after enjoying so much wealth offered on the fingertips, it is clear that, unlike the Temple of Jerusalem at the time of Jesus’ visit, this Temple is rich in “fruits”, that is, it is frequented by many faithful and admired by a lot of tourists. Here the commercial activities do not take the place of prayer and contemplation; it could be said that merchants manage those “additional services” that make a visit to a cultural heritage more enjoyable or that support the celebration of religious rites with comfort items.

And then, in cases like this, why hunt the merchants from the Temple?

Head Image: The Mosque of Hassan II, launched in 1993, dominates Casablanca’s promenade.

Il Tempio e i mercanti

Con i suoi tre milioni di abitanti e un hinterland di quattro milioni, Casablanca potrebbe sembrare a prima vista una metropoli cosmopolita e internazionale. Vivendola dal di dentro, invece, Casa (come familiarmente viene chiamata dagli abitanti) si rivela una città profondamente legata alle sue origini berbere in un paradosso di urbanistica nomade.

Abitata da “uomini liberi” (dal significato etimologico del termine “berbero”), la popolazione continua a mantenere usi e costumi propri delle tradizioni nomadi nordafricane. Nella Medina più antica, cinta dalle poderose mura in terra cruda rossa, i bianchi edifici che valsero il nome alla città formano un dedalo di strade e di vicoli ciechi brulicanti di vita dove ogni cosa sembra vivere nell’immediatezza del presente.

La Medina non ha un suq: è un suq. Ovunque si aprono attività commerciali dedicate alla vendita di verdure e ortaggi, abbigliamento e calzature, carne macellata e non (ci si può imbattere in una polleria con polli vivi in attesa di essere venduti o in tartarughe che attendono la stessa sorte mentre brucano foglie di lattuga!).

Marche Central. Tartarughe vive in vendita al mercato coperto del pesce di Casablanca.

Qui non serve necessariamente una bottega per esercitare un’attività: basta un tappeto steso per terra per improvvisare un banco di ortaggi (non proprio perfetti, ma oggi è molto di moda il bio e il chilometro zero!); un paio di macchine da cucire disposte lungo una strada per condurre un’avviata sartoria; sgabelli di plastica e ombrelloni da spiaggia per allestire una sala da pranzo provvisoria per un “ristorante” all’aperto la cui cucina è un semplice carretto su ruote munito di carboni ardenti e griglia.

Tappeto per la vendita di ortaggi nella Medina di Casablanca.

Sarte al lavoro nelle strade della Medina di Casablanca.

Street food e allestimenti temporanei per consumare la cena nella Medina di Casablanca.

Il cibo da strada è il padrone indiscusso di questo paesaggio urbano; si presenta in infinite varianti di allestimenti, tutti funzionali alla semplicità di montaggio/smontaggio, velocità di esecuzione e trattamento in loco di prodotti freschi. Molto gettonata in estate, anche per il clima caldo e secco, è la frutta di stagione come fichi d’india, ananas e cocco, sbucciati e porzionati al momento della vendita, e i succhi delle arance vaniglia, dei limoni di Fès e delle canne da zucchero estratti direttamente davanti al cliente.

Bancarella di succhi freschi nella Medina di Casablanca. Per le arance e i limoni vengono utilizzati degli spremiagrumi mentre per l’estrazione del succo della canna da zucchero viene utilizzato uno spremitore elettrico apposito: in un foro viene inserita la canna, da un beccuccio esce il succo e da un altro foro esce il residuo della canna spremuta.

Lo shua (barbecue marocchino) è il re del cibo da strada: pesce e carni di agnello, manzo, pollo e coniglio, marinati con cumino, coriandolo, curcuma, zafferano e pepe (la cucina marocchina è la più speziata del nord Africa), riempiono con i loro aromi portati dal vento l’aria della città. Il fumo che si leva dalle braci è davvero la miglior pubblicità per attrarre i clienti, che vengono serviti utilizzando il batbout, il tradizionale pane piatto, come unica stoviglia. Anche questa pratica risale alla tradizione maghrebina: non utilizzare piatti e posate, mangiare con le mani (solo la mano destra, la sinistra è considerata impura!), usare il pane come una tasca per contenere le carni, i contorni e i sughi, consente un notevole risparmio nella produzione e nel trasporto di suppellettili da cucina che, per una società nomade, costituisce uno dei principali problemi da affrontare nei frequenti spostamenti.

Barbecue all’ora di cena. Salsicce e cipolle, condite con salsa piccante, spezie e coriandolo fresco, vengono servite all’interno del pane aperto a tasca e accompagnate da patatine fritte.

Così ogni giorno, all’ora di pranzo e di cena, la Medina si popola improvvisamente di improvvisati banchetti di street food, ma è il lungomare di Casablanca, la Corniche Ain Diab affacciata sull’Oceano Atlantico, il vero protagonista di un rito collettivo che si celebra tutte le sere.

Quando il re Hassan II decise il luogo dove erigere la nuova Moschea, una delle più grandi del mondo ed oggi edificio simbolo del Marocco, fece una scelta volutamente fuori dal comune: piuttosto che costruirla all’interno della città, volle collocarla nello sconfinato orizzonte dell’Oceano Atlantico, stagliandola sul tramonto dell’estremità occidentale del continente, rendendo così omaggio al Maghreb, etimologicamente le lieu où le soleil se couche.

Appoggiata su un promontorio roccioso sul mare e costruita per due terzi su ingegnose sostruzioni in cemento armato, l’edificio è in piena comunione con gli elementi della natura: il pavimento in vetro lascia fruire delle onde del mare durante la preghiera, il soffitto scorrevole accoglie il cielo nella sua immensità, le fondazioni si allungano come radici nella roccia. Ogni sera questo potente landmark regala uno degli spettacoli più straordinari che l’opera dell’uomo abbia saputo creare insieme alla natura: il sole che tramonta sul mare, tinteggiando con i suoi raggi di fuoco l’orizzonte, riverbera la sua luce sulle superfici marmoree dell’edificio e sui brillanti zellige verdi, bianchi e ocra del minareto, il più alto del mondo.

All’appuntamento con il tramonto partecipa una moltitudine eterogenea di persone che si raccoglie sulla vasta piazza antistante la moschea e lungo il Parc Sindibad, il parco sul fronte a mare che ha valorizzato con efficienti ed eleganti interventi di recupero e arredo urbano il waterfront. Intorno alla moschea non si celebra una funzione religiosa, quanto si condivide in modo spontaneo e pacifico un rito di passaggio dal giorno alla notte che non ha nazionalità né confini religiosi o ideologici.

Il sentimento vissuto da ciascuno, nella sua indicibilità e intrasmissibilità, è diverso, ma è accomunato da un senso di armonia con la natura e con il mondo. I più giovani lo esprimono tuffandosi dall’alto delle mura di protezione della Moschea nei flutti gelidi dell’Atlantico, facendo a gara tra di loro a chi arriva più lontano. Gruppi di ragazzi improvvisano un po’ di musica con tamburi e tamburelli, intonando i tradizionali canti a domanda e risposta delle antiche tribù berbere. I mercanti si fanno trovare pronti per aggiungere, a questo momento di intimità con la natura, il piacere del palato.

Ragazzi che si tuffano nell’oceano dalle mura della Moschea di Hassan II.

Come la tradizione del maghreb insegna, non occorre un ristorante per sfamare una folla; baracchini, carretti, strapuntini portati a spalla appaiono nel momento più opportuno per offrire alla folla ogni genere di comfort food, in accordo con le stagioni e la portabilità del cibo.

Venditore ambulante sul lungomare di Casablanca accanto alla Moschea di Hassan II.

Ecco quindi che in estate trionfano le lumache, servite in tazze da tè scompagnate dove va a finire anche il liquido di cottura da sorseggiare alla fine; le pannocchie sfrigolano sulle braci che regalano ai chicchi un irresistibile gusto di affumicato; si friggono le patate affettate in allettanti fogge spiraliformi; si sgranocchiano noci e noccioline e si sorseggia l’immancabile tè alla menta servito caldo e dolcissimo in piccoli bicchieri di vetro.

Venditore ambulante di lumache accanto alla Moschea di Hassan II. Le lumache bollite vengono servite dentro tazze da tè insieme al liquido di cottura.

Il tramonto alla grande Moschea è l’habitat ideale dove si propagano i briouates: si tratta di una tipica preparazione marocchina fatta apposta per dimensioni, sapore e packaging per essere consumata velocemente e all’aperto. All’interno di un guscio croccante di pasta brick, avvolto a triangolo o a cilindro e fritto in modo da non far scappare nulla del goloso ripieno, si gusta una deliziosa farcia speziata nelle varianti alla carne, al pesce, al formaggio o alle verdure. Una recente contaminazione con gli ingredienti provenienti da altre cucine del mondo ha portato nel ripieno dei briouates dell’estremo occidente anche gli spaghetti di riso dell’estremo oriente che, esaltati dalle spezie marocchine e insaporiti dalla rosolatura di carni e pesci locali, hanno contribuito alla creazione di un cibo da strada tra i più riusciti al mondo.

Briouates a forma di triangolo e di cilindro ripieni di spaghetti di riso, spezie e pesce, serviti con carote sottaceto e olive, in vendita accanto alla Moschea di Hassan II.

Al termine del tramonto, e dopo aver goduto di tanta ricchezza offerta sulla punta delle dita, appare chiaro che, a differenza del Tempio di Gerusalemme al tempo della visita di Gesù, questo tempio è ricco di “frutti”, ossia è frequentato da numerosissimi fedeli e ammirato da altrettanti turisti. Qui le attività commerciali non prendono il posto della preghiera e della contemplazione; si potrebbe dire che i mercanti gestiscono quei “servizi aggiuntivi” che rendono più piacevole la visita ad un bene culturale o che supportano con generi di conforto la celebrazione dei riti religiosi.

E allora, in casi come questo, perché mai cacciare i mercanti dal Tempio?

Head image: La Moschea di Hassan II, inaugurata nel 1993, domina il waterfront di Casablanca.