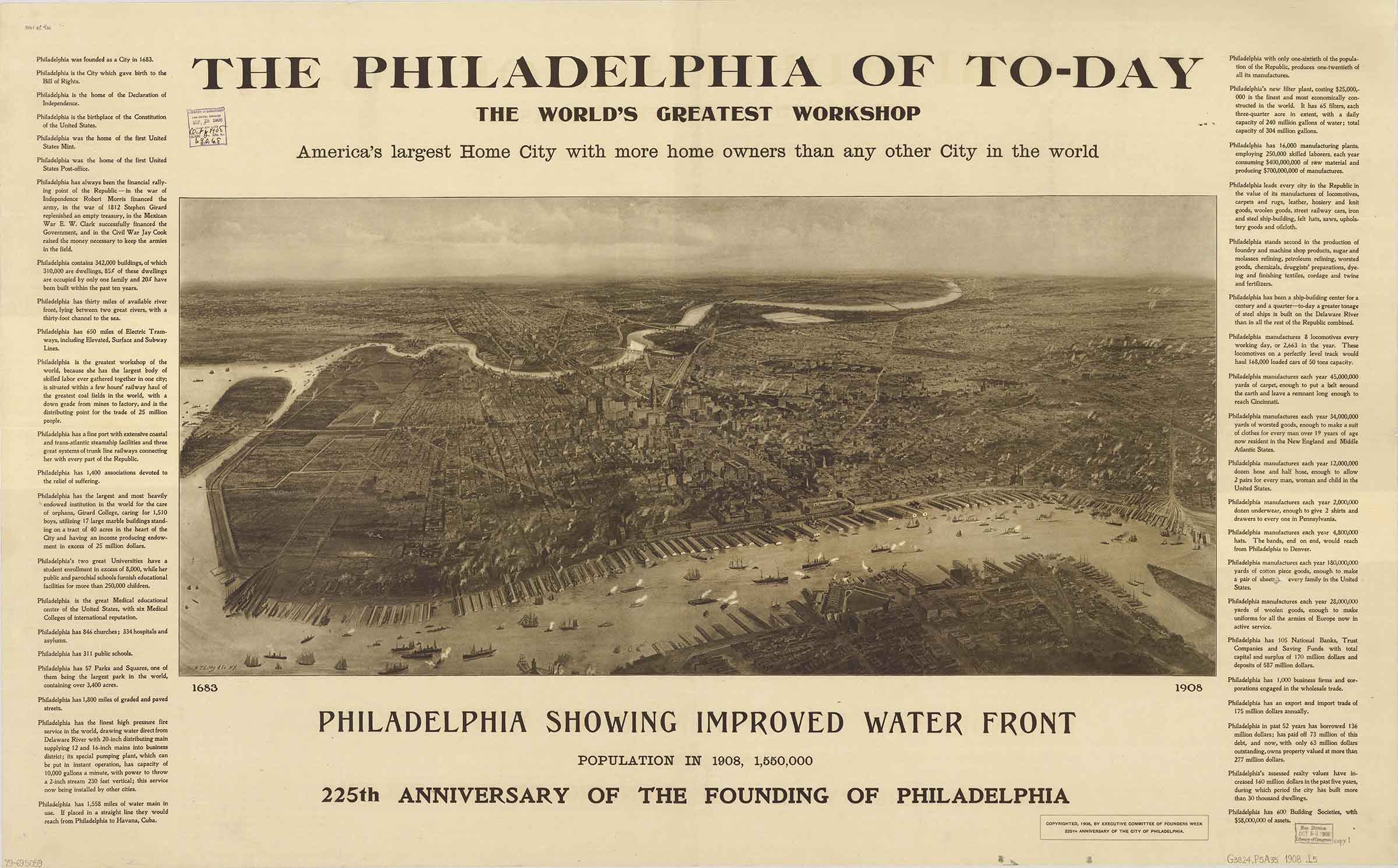

Philadelphia is a city of 1.58 million people located in the southeastern corner of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania between the cities of New York and Washington, DC along the Eastern seaboard of the United States. As the principal city of one of the original 13-British North American colonies, Philadelphia and its Delaware River port played an important role in United States history despite being situated 100-miles upriver from the Atlantic Ocean. With a deep and protected port and easy access to plentiful raw materials in the hinterland, Philadelphia was a major colonial economic hub before growing to become an industrial powerhouse in the period between the American Civil War (1860-65) up to the end of World War II (1945) – earning the sobriquet “Workshop of the World” [2].

“The Philadelphia of to-day, the world’s greatest workshop: America’s largest home city with more home owners than any other city in the world”, 1908. (Source: https://www.loc.gov/item/79695059/)

By mid-20th century, Philadelphia’s fortunes, like many formerly-industrial Northeastern cities, began to fade. With the advent of the interstate highway system and the flight of industry to green fields in the South, Philadelphia entered a nearly-fifty-year period of depopulation, deindustrialization and disinvestment. The port, once Philadelphia’s lifeline to the world, began to shrink in importance as many port-related industries and functions shuttered.

The Penn’s Landing Corporation was created in 1970 to oversee the development of a revitalized Delaware River waterfront on 35-acres of public land adjacent to the city center. Despite repeated attempts to entice large-scale development such as residential and office towers, festival markets and entertainment complexes, the costs to build on river fill on a strip of land severed from downtown by both an interstate highway and a wide surface road required large government subsidies – making development of this scale nearly impossible. In 2004, portions of the riverfront itself were eyed by state legislators as the location for two gaming casinos.

At the same time, Philadelphia was experiencing the first increase in population since 1950 [3] and the neighborhoods along the central Delaware riverfront [4] were seeing shifts in demographics from once ethnic working-class enclaves to ones now attracting artists, young adults (millennials) and returning retirees (baby boomers). Simultaneously, a real estate boom in neighborhoods along the river fueled by a city property tax-abatement and easy access to credit before the 2008 global market crash placed pressure on local officials to respond to a growing community backlash against gated communities and speculative and large-scale development – including casinos.

At this time, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission and the Penn’s Landing Corporation had lost the public trust as there were no progressive plans to guide the development of the waterfront. PennPraxis [5], a non-profit arm of the University of Pennsylvania, was asked to lead a public planning effort in 2006 for 1,100-acres of former industrial land along a 7-mile stretch of largely privatized riverfront [6]. More than 200-public meetings were attended by over 4000-Philadelphians across a 13-month period to inform the planning process.

The resulting Civic Vision for the Central Delaware [7] put forth the recommendation to extend of Philadelphia’s street grid across the waterfront post-industrial properties. Organized around a series of waterfront parks located every ½-mile connected by a continuous riverfront trail, the vision led with public space and public waterfront access. Thus, establishing a framework for development that would “tame” the large and inaccessible former-industrial properties that were separated from the city by the breach of Interstate 95 and reclaim the water’s edge for the citizens of Philadelphia.

The plan was not met with universal acceptance. Developers felt that the imposition of a street grid was an illegal taking of private property and longshoreman viewed the plan as a threat to their way of life. Despite these obstacles, the plan moved from a civic vision based on shared values to an approved master plan [8] by the then-reformed Delaware River Waterfront Corporation (DRWC) and it was officially adopted by the Philadelphia Planning Commission in 2012.

“Master Plan for the Central Delaware”, 2011. (Source: Delaware River Waterfront Corporation)

Adaptive Reuse and Creative Placemaking as a Catalyst for a New Waterfront Identity

It is important to note that much of the historic building fabric along the central Delaware has been lost with the construction of Interstate 95 in the 1970s and 80s, the decline of industry and the relocation of former Delaware River port functions to other parts of the city. Still, enough historic fabric remained to inform an urban design identity for the new district and as a way to demonstrate the value of heritage preservation and adaptive reuse in placemaking.

To show that change could come quickly to the central Delaware after decades of false starts dependent on mega-projects, DRWC now focused on a number of early action projects designed to express the planning principles of public access, identity and connectivity as the leading edge of change. Along with creating portions of the riverfront trail along with some new parks on the 7-mile stretch of river, the following three bellwether projects- the transformation of two former municipal piers (Piers 9 and 11) into public spaces and the repurposing of an outdated high-pressure fire water pumping station as an arts venue- serve as an exemplar for urban design excellence, adaptive re-use of existing building fabric and sensitivity to context. They are clustered around the intersection of Columbus Boulevard and Race Street with an on-grade connection beneath the interstate to the adjoining neighborhood of Old City.

Importantly, they help establish the case for creative placemaking – defined by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) as when “…artists, arts organization and community development practitioners deliberately integrate arts and culture into community revitalization work…” [9] – as an integral part of city building. It should be noted that ArtPlace America [10], a ten-year (2010-20) creative placemaking initiative of the NEA in partnership with national philanthropic foundations including, locally, the William Penn and Knight Foundations, provided support, and national validation, for some of the early projects on the Delaware. Along with a 2013 grant to the FringeArts festival for the reclamation of the pumping station project, a 2013 ArtPlace America grant also enabled DRWC to create a river stage [11] on a formerly under-utilized central riverfront public space – becoming a highly successful public gathering place that continues to attract a diverse summer audience through a mixture of local food, fanciful hammocks and dynamic programming.

Proof of Concept: Race Street Pier, FringeArts and Cherry Street Pier

The first public space project to be realized as part of the waterfront corporation’s master plan was Race Street Pier [12] which opened in 2011. The pier, originally known as Municipal Pier 11, was constructed in 1896 and included a two-story building with shipping functions below and recreational uses above. Long derelict and devoid of its port-related superstructure at the time of the planning process, the landscape architects, Field Operations, and DRWC created an elegant promenade on the existing substructure and pilings that rises 12-feet from street level across 540-feet to form a stunning overlook alongside the Benjamin Franklin Bridge with sweeping views onto the wide expanse of the Delaware River below. Generous amphitheater-style seating is used for sun bathing and as a performance venue. While planned before the ArtPlace America program began, Race Street Pier signaled the creation of well-designed public space as the way to attract the public to the river and thereby incentivize development. As such, it represented a welcome and noteworthy departure from the plethora of past attempts at large-scale development as the catalyst for waterfront development over the preceding forty years – effectively declaring that the era of “Big Bang” economic development between the public and private sectors was effectively over along the Delaware.

Race Street Pier, Pier 9 and Fringe Arts Building from Benjamin Franklin Bridge. (Source: Delaware River Waterfront Corporation, Photo credit: Matt Stanley)

Race Street Pier Promenade. (Source: Delaware River Waterfront Corporation, Photo credit: Neal Santos)

FringeArts, [13] a non-profit seasonal performing arts organization founded in 1997, had been purposely without a home base. The organization produces a highly-acclaimed fall festival utilizing unique and forgotten spaces across changing neighborhoods in the city as performance venues. In 2013, the festival, while maintaining its annual fall programming, renovated a former high-pressure fire truck pumping station built in 1903 and located across the street from the Race Street Pier. In choosing to repurpose the pumping station into an adaptable theater space along with a restaurant and beer garden, the Fringe created a vibrant hub to “advance the global dialogue about art”. A 2013 ArtPlace America grant enabled the group to create and activate an outdoor performance space along the underutilized Delaware waterfront as part of their adaptive reuse of the pumping station. Events now include an open-air circus and movie nights along with avant-garde programming offered inside the new venue. While the festival is still staged across the city, the FringeArts building now brings people and culture to the waterfront throughout the year.

Interior of reclaimed pumping station as restaurant at FringeArts, 2014. (Source: FringeArts, Photo credit: Peggy Woolsey)

Beer Garden at FringeArts, 2014. (Source: FringeArts, Photo credit: Johanna Austin)

In late-2018, the waterfront corporation opened Cherry Street Pier [14] in what was formerly known as Municipal Pier 9 – a massive enclosed shed that was completed in 1919 with an imposing poured concrete headhouse along Delaware Avenue. Located to the south of Race Street Pier and also across the street from Fringe Arts, Cherry Street Pier is a year-round, mixed-use public space created within an existing 55,000-sf 100-year old shell. Along with public programming and serving as a venue for local arts it aims to help draw from a wide-range of non-traditional audiences by supporting emerging artists and helping to create new and creative communities. Programming is designed to be flexible and diverse including markets and immersive installations. Funding for the project came from the William Penn and Knight Foundations – both national funders of ArtPlace America.

Cherry Street Pier Headhouse, 2018. (Source: Delaware River Waterfront Corporation, Photo credit: Maria Young)

Garden at Cherry Street Pier, 2018. (Source: Delaware River Waterfront Corporation. Photo credit, Maria Young)

Leading with Placemaking

These three projects are emblematic of the use of historic fabric and placemaking in creating a new identity for the central Delaware. Clustering around an intersection alongside an historic suspension bridge, they signal that the waterfront is an adaptive and incremental environment (versus one created from whole cloth) where new ideas are explored, diversity and inclusion is valued, and the past is a potent part of the present. It is precisely this focus on the integration of the arts, public space and preservation (particularly in the FringeArts and Cherry Street Pier projects) as the leading edge of change that has upended the decades-old Philadelphia adage of “any development is good development.” The old way of thinking brought Philadelphia a waterfront Walmart surrounded by parking on former port land. The new way of thinking brings a plethora of new public spaces enlivened by cutting-edge programming and supported by local food and beverage purveyors. They place the public first as a driver of sustained change – before the development community – and in so doing is yielding dividends in how the waterfront is finally being perceived and realized. An exciting and vibrant public realm brings people, which helps to build a buzz and create an identity which in turn attracts developers’ attention.

Indeed, arts, planning and preservation as an economic development tool is not a new idea. What is different in Philadelphia along the central Delaware waterfront and within the creative placemaking field as a whole, is the intentional manner in which arts and community development are positioned as key players in establishing an economic development agenda. These efforts are hyper-local, fine-grained and inexpensive compared to the traditional top-down arts district model that might include a new museum (think Bilbao) or concert hall (think Hamburg).

In Philadelphia, along the Delaware, adaptive reuse and historic preservation are being used to create a new and authentic identity for the waterfront. Rather than cut and paste urban design solutions from other cities (think of how Manhattan’s enormously successful High Line Park is being replicated across the United States) or seek to attract national development teams, the early implementers of the waterfront plan for the central Delaware are leading with local community and local arts and working within existing building fabric. Importantly, these projects serve as proof-of-concept for the power of placemaking, laying the ground work for more ambitious public space projects such as an $225 million, 8-acre park designed as a cap over the interstate highway – the site of previous large-scale development proposals [15].

These projects of DRWC and Fringe Arts demonstrate the power of creative placemaking at the service of a broader economic development agenda. Recognizing that authenticity derives from the creation of an honest sense of place, the projects integrate public space and the arts using the preservation and adaptive reuse of existing buildings and structures as the starting point for a new future along Philadelphia’s waterfront.

Notes

[1] Markusen, A, Gadwa A, (2010) “Creative Placemaking”, Mayors’ Institute on City Design and the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, DC.

[2] Evans, O, (1990), “Workshop of the World”, Chapter for the Study of Industrial Archeology, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

[3] https://www.inquirer.com/news/a/philadelphia-population-growth-census-south-jersey-20190418.html

[4] An 1,100-acre acre bounded by Oregon Avenue at the south, Allegheny Avenue at the north, the river to the east and Interstate 95 to the north. 60,000 Philadelphians live within a ½-mile or 10-minute walk of this area.

[5] The author was the founding director of PennPraxis, the non-profit applied research arm of the School of Design of the University of Pennsylvania and led the 2006-07 planning process. Partners included the Penn Project for Civic Engagement and the planning firm of WRT.

[6] The process was authorized by executive order of the mayor of Philadelphia and funded by the William Penn Foundation.

[7] See PennPraxis, WRT, Philadelphia City Planning Commission and the William Penn Foundation.

https://issuu.com/pennpraxis/docs/civic-vision-for-the-central-delaware

[8] https://www.delawareriverwaterfront.com/planning/masterplan-for-the-central-delaware/full-plan

[9] https://www.arts.gov/artistic-fields/creative-placemaking

[10] https://www.artplaceamerica.org/

[11] https://www.delawareriverwaterfront.com/places/spruce-street-harbor-park

[12] https://www.delawareriverwaterfront.com/places/race-street-pier

[14] https://www.cherrystreetpier.com/

[15] https://www.inquirer.com/news/i95-park-cap-delaware-river-curious-philly-20190624.html

Head image: Cherry Street Pier Pre-Construction. (Source: Delaware River Waterfront Corporation, Photo credit: James Abbott)