╔

(yet) It’s a Man’s World: Gender Issues in the Maritime Industry

Historically, the maritime industry has been male dominated. Apart from the stark disparities in numbers, traditionally, men were given more recognition and power to take part in the maritime labor market. However, in modern society, particularly since the 1990s, there has been growing attention to the valuable role that women can play in various transportation industries, particularly the maritime sector, training and recruiting female seafarers (Belcher et al. 2003).

“Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls” is one of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1]. Reaching this SDG’s Goal 5 becomes even more challenging in the maritime transport sector, where female contribution remains low. According to the Seafarer Workforce Report [2] from BIMCO and the International Chamber of Shipping, women make up less than 1.3% of the 1.89 million global seafarer workforce (the year 2021). Female contributions were mainly found in the cruise and ferries sector, which are generally lower paid and less protected. Nevertheless, the data for 2021 shows a positive trend in gender balance: the report estimates 24,059 women serving as seafarers, which is a 45.8% increase compared to 2015. Also, women are less visible in the leadership positions (Vo et al., 2023).

One of the first attempts to support gender equality and female empowerment was made by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), one of the UN’s specialized agencies. Under the three-pillar slogan of “Training-Visibility-Recognition,” IMO’s Women in Maritime Programme was launched in 1989 [3]. The program encourages female inclusion in the maritime industry by supporting initiatives on training, mentorship, and networking opportunities, therefore supporting career development opportunities in maritime administrations, ports and maritime training institutes. Such initiatives and efforts to empower women in the maritime community have been recognized as crucial for the sector’s growth and sustainability (Kitada et al., 2019). Furthermore, Romero Lares (2017) analyses the IMO’s policies on gender equality with reference to the World Maritime University initiatives and the number of female graduates. The findings show that adopted policies have been relatively successful in improving the gender balance of academics already from the late 1990s: an increasing number of female graduates was recorded, from 2.85% in 1984-85 to 19.7% in 2016 (a total number of 859 female graduates out of 3,500 students).

The academic literature on gender studies and women working in the maritime transport sector is young but quite promising. A very recent publication by Stavroulakis et al. (2024) discusses the unbalanced gender dimension in the maritime domain and the possible discrimination, exclusion, and harassment of the few women working on board vessels and onshore. Their empirical findings show that both women and men can specifically contribute to the added value of the maritime sector, and therefore, achieving a fully sustainable paradigm requires immediate action and systematic restructuring in the industry. Conceptualizing the relationship between postmodernism and maritime gender culture, Dragomir (2019) introduces the notion of “gender shipping”, which is an emerging trend of benchmarking in the maritime sector towards a socially responsible attitude from the companies and to involve them voluntarily adopting and promoting gender equality policies. Accordingly, the following solutions have been suggested to increase female seafarers awareness and empowerment:

- Advance maritime education and training to be more inclusive of women.

- Encourage shipping companies to implement gender-sensitive policies and practices.

- Strengthen international regulations and strategies to support the recruitment and retention of women in the maritime industry.

Some studies argue that the maritime industry has been undergoing significant changes, including advancements in automation technology, which have implications for gender parity within the sector. On this matter Kim et al., (2019) suggest that automation can potentially help to remove the barriers in the social environment and the physical working conditions. Nevertheless, this requires “structural changes from a systemic perspective, to ensure that the system, from design to operations, could conform female characteristics and life patterns” (p.590).

Contributing to this gradually growing yet scant literature, in this short paper, I will provide an overview of the status of women in the maritime sector and the efforts and policies in place to tackle the challenges women face in this sector, with a focus on Northern Europe.

Towards Social Sustainability in Ports: Evidence From the North Sea

Although the environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability in ports have been widely explored in the literature, only a few scholars have considered the social pillar, particularly considering gender and female inclusion. If we consider the women workforce as a proxy for the social dimension of sustainability in the maritime sector, it is evident from the data that this environment continues to suffer from a talent gap and a lack of female executives, mainly due to the issues of work-life balance (Vo et al., 2023). The importance of gender equality in achieving social sustainability in ports has also been examined by Sanrı (2022). Here, empirical findings show that by prioritizing recruitment policies – for transparent and inclusive hiring practices to attract female employees – and other supportive measures (such as work-life balance efforts), ports can work towards reducing the gender gap and fostering a more inclusive workplace.

Exploring how some European ports contribute to sustainability by promoting gender equality measures, Barreiro-Gen et al. (2021) have identified five stages: (i) gender segregation: ports often start with significant gender segregation, which needs to be overcome; (ii) compliance with national laws and regulations: ports must comply with national gender equality laws; (iii) gender equity: ensuring fairness and addressing historical disadvantages faced by women; (iv) gender equality: achieving equal rights, responsibilities, and opportunities for all genders; (v) sustainable ports: Achieving greater sustainability through gender equality. The findings were used to develop a “Gender equality for sustainability in ports” framework, which outlines the stages and factors influencing gender equality efforts in ports.

The maritime sector continues to be of strategic importance for trade, tourism and globalization in the EU region. As reported by the European Commission on Mobility [4] and Transport (2015), 74% of commodity flows pass through Europe’s ports, and more than 400 million passengers are transported by EU ports. It is assumed that about 800,000 enterprises in EU ports, generating 3 million jobs, directly and indirectly (Van Hooydonk, E. 2014). What is the share and contribution of women dockworkers and seafarers?

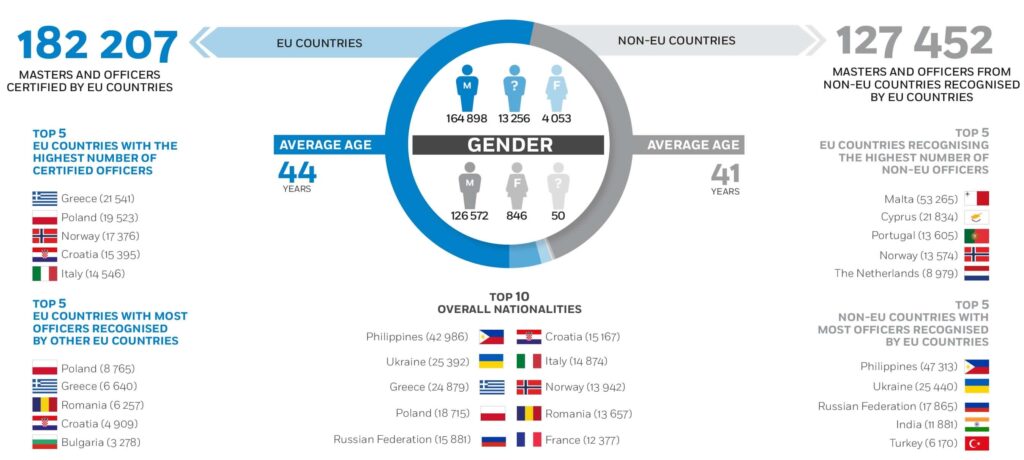

The number of female workers in the EU maritime sector resembles the global record, with an overrepresentation of men: female certified masters and officers are below 1.8% of the total number of EU Member States-flagged vessels (European Maritime Safety Agency—EMSA, 2023). Figure 2 illustrates an overall picture of this significant inequality in the number of male and female certified seafarers in the EU, as well as the geography of certified workers: In northern Europe, only Norway and the Netherlands are among the top five countries with the highest number of certified officers issued by EU and non-EU countries (year 2021).

Figure 1. Number and distribution of seafarers in the EU – the Year 2021. (Source: European Maritime Safety Agency—EMSA – https://www.emsa.europa.eu/newsroom/latest-news/item/4950-seafarer-statistics-in-the-eu-statistical-review-2021-data-stcw-is.html).

The European Commission report on social aspects within the maritime transport sector (European Commission, 2020) reveals that gender and diversity issues remain highly problematic in the maritime transport sectors globally and within the EU. The representation of women is very low, with little sign of significant improvement over time. Despite some positive examples in the Nordic countries and the Netherlands, women often hold lower-status, lower-paid positions and, like other marginalized groups, face harassment, stereotyping, and discrimination. Although these issues are widely recognized, there is little consensus on effective solutions, and most actions taken have been preliminary and insufficient relative to the scale of the issues.

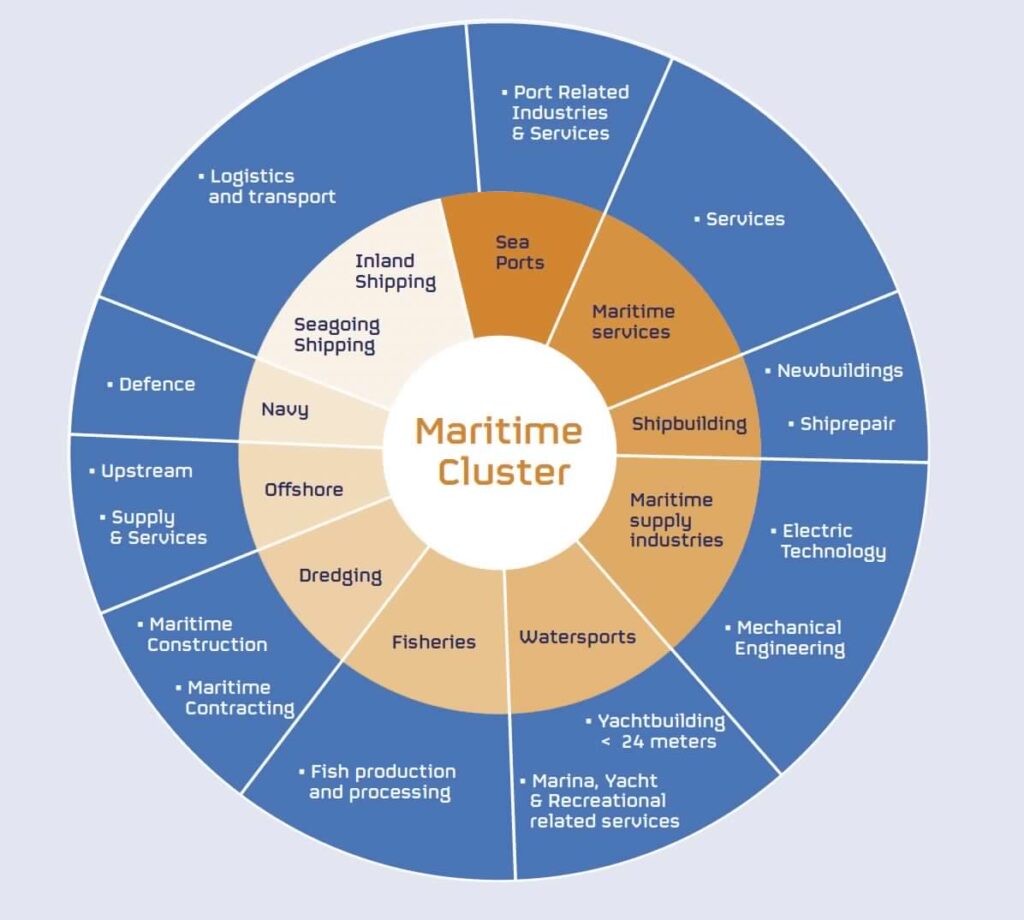

In the Netherlands, the maritime sector has historically been an integral and significant element of the economy: in 2022, the maritime cluster (see Figure 2) generated an added direct value of €25.9 billion, which accounts for 3.2% of the Dutch GDP; the combined port and maritime cluster rises to 7.5% of the national GDP. The maritime cluster has over 305,000 workers (3% of total employment), with a gender distribution of 77% Male and 23% female (The Dutch Maritime Network, 2023). According to the Royal Association of Netherlands Shipowners, about 5,000 Dutch seafarers are employed on board the Dutch fleet and over 22,000 with other nationalities [5].

The Dutch Maritime Strategy 2015-2025 [6] calls for a healthy business climate that necessitates investing in human capital and innovation, among other areas. The government of the Netherlands encourages maritime industries and nautical colleagues to train high-quality young people, ensure an attractive maritime profession and provide multiple development opportunities and attractive career prospects. Based on the recent European Commission survey (European Commission, 2020), highlights the career flexibility and the possibility of a career path that stretches from jobs onboard to onshore, which is acknowledged as key factors to enhance the attractiveness of the maritime sector, especially to young people. This factor is particularly important in attracting female workers, as it may help overcome the issue of work-life balance highlighted in several studies. Nevertheless, in this report, the Netherlands, among other Northern Member states (such as Sweden and Denmark), raised the problems related to harassment, discrimination and employment conditions for female workers.

Figure 2. The Dutch Maritime Cluster. (Source: The Dutch Maritime Network – https://maritiemland.nl/en/home/).

In the Netherlands, the Port of Rotterdam holds significant importance at the national and regional levels. A cornerstone for the Dutch economy, it serves as a vital hub for trade, industry, and innovation also at the EU region and globally. The Port of Rotterdam promotes diversity and inclusion. The diversity policy contributes towards gender balance and diverse composition of workers, as well as better decision-making and enhanced agility and innovation. Becoming inclusive and the port’s social impact has been reflected in the Port Authority’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) statement [7]: one of the three main components is ‘People & Work’, which fosters sustainable employment across various social groups. In the ‘Rotterdam Port Vision [8]’ document, one of the challenges was identified as ‘social transition’ in terms of changing jobs and skills and adapting continuously to technological and digital developments, which requires a continuous dialogue between government, education and research institutes, and the business community. Although the term ‘gender’ or ‘women/female inclusion’ has not been mentioned in these documents, I believe this can be a good starting point for tackling such social issues.

Concluding Remarks: Introducing ‘Gender’ as a Pillar of Sustainability

The maritime industry is significantly male dominated, with women making up a very small percentage of the workforce. Nevertheless, since the turn of the century, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of gender diversity and inclusivity in port operations and management. Maritime ports play a key role in global production and the sustainability agenda. Despite their significant impact, gender equality and its related issues have been a low priority in port sustainability efforts. Moreover, as underlined during the ‘2024 International Day for Women in Maritime: Shaping the future of maritime safety’ [9], the rise of digitalization, automation, and green technology in the maritime sector will necessitate new skills and potentially create new career opportunities for women.

Academic literature highlights that gender issues are integral to sustainability, with women playing a crucial role in contributing to it. However, as discussed in this paper, more inclusive ports and growing female participation will contribute to the social sustainability of the port industry. This is, on the one hand, beneficial to society while empowering women on different levels, and on the other hand, it will add a new dimension and (socio-spatial) layer to the relationship between the port and its city-region. Yet, the maritime industry (both public and private domains) must work on its policies and strategies to become more attractive to women at all stages of their careers, offering clear paths for advancement from entry-level roles to leadership positions (IMO, 2021).

Although the maritime industry and many port authorities in Europe and worldwide are working on their visions and charters for a more sustainable future (mainly based on the UN’s SDGs), addressing social sustainability in terms of ‘gender issues’ and, therefore, directly including ‘gender’ in their agenda is generally neglected. I believe that promoting female participation is not just a matter of social justice and social progress. More women seafarers will potentially:

- contribute to the shortage of certified officers, recently warned by the BIMCO/ICS Seafarer Workforce Report [10];

- bring diverse perspectives and skills to better understand the needs of diverse stakeholders;

- create more inclusive workplace cultures;

- improve performance and sustainability in the industry.

HEAD IMAGE | Female Dock Worker. (© Corepics Vof | Dreamstime.com; Photo 47051675).

╝

NOTES

[1] https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/.

[2] https://www.ics-shipping.org/press-release/new-bimco-ics-seafarer-workforce-report-warns-of-serious-potential-officer-shortage/.

[3] https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/TechnicalCooperation/Pages/WomenInMaritime.aspx.

[4] https://transport.ec.europa.eu/index_en/.

[5] https://www.kvnr.nl/en/labour#:~:text=Dutch%20seafarers%20have%20a%20reputation,seafafarers%20with%20a%20different%20nationality.

[6] https://www.noordzeeloket.nl/en/policy/maritime-strategy/.

[7] https://www.portofrotterdam.com/en/about-port-authority/port-authority-society/corporate-social-responsibility/.

[8] https://www.portofrotterdam.com/sites/default/files/2021-06/port%20vision.pdf/.

[9] https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/pages/International-Women-In-Maritime-Day-2024.aspx/.

[10] https://www.ics-shipping.org/press-release/new-bimco-ics-seafarer-workforce-report-warns-of-serious-potential-officer-shortage/.

REFERENCES

Barreiro-Gen, M., Lozano, R., Temel, M., & Carpenter, A. (2021). Gender equality for sustainability in ports: Developing a framework. Marine Policy, 131, 104593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104593/.

Belcher, P., Sampson, H., Thomas, M., Veiga, J., & Zhao, M. (2003). Women seafarers: global employment policies and practices. ILO.

Dragomir, C. (2019). Gender in Postmodernism Maritime Transport. Postmodern Openings, 10(1), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.18662/po/61/.

European Commission. Directorate General for Mobility and Transport. (2020). Study on social aspects within the maritime transport sector: Final report. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2832/49520/.

European Maritime Safety Agency – EMSA (2023). Seafarer Statistics in the EU – Statistical review (2021 data STCW-IS). Retrieved from https://www.emsa.europa.eu/newsroom/latest-news/item/4950-seafarer-statistics-in-the-eu-statistical-review-2021-data-stcw-is.html/

IMO (2021). Women in MaritimeSurvey 2021. A study of maritime companies and IMO Member States’ maritime authorities. Retrieved from: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/TechnicalCooperation/Documents/women%20in%20maritime/Women%20in%20maritime_survey%20report_high%20res.pdf/.

Kim, T., Sharma, A., Gausdal, A. H., & Chae, C. (2019). Impact of automation technology on gender parity in maritime industry. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, 18(4), 579–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-019-00176-w/.

Kitada, M., Carballo Piñeiro, L., & Mejia, M. Q. (2019). Empowering women in the maritime community. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs, 18(4), 525–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-019-00188-6/.

Romero Lares, M. C. (2017). A Case Study on Gender Equality and Women´s Empowerment Policies Developed by the World Maritime University for the Maritime Transport Sector. TransNav, the International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation, 11(4), 583–587. https://doi.org/10.12716/1001.11.04.02/.

Sanrı, Ö. (2022). Evaluation of Gender Equality Criteria Related to Social Sustainability in Ports. EMAJ: Emerging Markets Journal, 12(1), 86–93. https://doi.org/10.5195/emaj.2022.256/.

Saunders, F. P., Gilek, M., & Tafon, R. (2019). Adding People to the Sea: Conceptualizing Social Sustainability in Maritime Spatial Planning. In J. Zaucha & K. Gee (Eds.), Maritime Spatial Planning (pp. 175–199). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98696-8_8/.

Stavroulakis, P. J., Papadimitriou, S., & Tsirikou, F. (2024). Gender perceptions in shipping. Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs, 16(2), 238–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/18366503.2023.2223867/.

The Dutch Maritime Network (2023). The Dutch Maritime Cluster Monitor 2023.

Van Hooydonk, E. (2014). Port Labour in the EU. Labour Market, Qualifications & Training, Health & Safety, Volume 1 – The EU Perspective. Portius.

Vo, L.-C., Lavissière, M. C., & Lavissière, A. (2023). Retaining talent in the maritime sector by creating a work-family balance logic: Implications from women managers navigating work and family. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 53(1), 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-09-2021-0409/.