Located where a number of important rivers meet the North Sea, the Netherlands and Belgium contain major sea and inland ports. During the Golden Age, cities like Amsterdam and Antwerp were global trading hubs. Remnants of buildings from that period remain in the historic port areas of both cities. The National Shipping Museum in Amsterdam and the reconstruction of the Amsterdam, a so-called East Indiaman, a ship of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) used for trading with Asia, reflect the long-term history of the Dutch capital. These old port structures are located near the historic center of Amsterdam and in the vicinity of several cultural institutions, such as the Nemo Science Museum and the Concert Hall. Restored historical warehouses such as Pakhuijs de Zwijger make the area a recognizable and well-studied example of urban waterfront revitalizations of urban harbours worldwide. The presence of both sea and river cruise berths have established the area a centre of maritime heritage in proximity of the inner city, and a postcard case of waterfront renewal as an economic motor.

The former NDSM Shipyard in Amsterdam Nord has been transformed into a space for creative industry. (https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/NDSM_terrein#/media/File:Smederij_NDSM.JPG)

The success of Amsterdam as a tourist magnet and an economic powerhouse has led to urban development and a high demand for housing construction in diverse urban port areas. New waterfront redevelopment has occurred just a 15-minute boat ride from the centre, across the waters of the IJ-a former bay connected via a canal to the North Sea. The areas north of the IJ host the Eye Film Institute and other cultural institutions. The area has become a hub for creative industry housed in the remaining buildings including the Nederlandsche Dok en Scheepsbouw Maatschappij (NDSM) presented by Hester Aardse. The NDSM shipyard, for example, went bankrupt in 1984 and has since become a space for artists, exhibitions and festivals. It also includes some offices and student housing [1]. The redevelopment of the former port area has increasingly extended from the historic port to the more recent, working areas. It has recently been announced that a 100-year old-listed building, the former flour mill warehouse Pakhuis De Vrede in Zaandam, may become home to a Tony’s Chocolonely factory with production and visitor facilities [2].

The Read Star Line Museum in Antwerp, 2014. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Star_Line#/media/File:Red_Star_Line_Museum.jpg)

Similar waterfront renewal projects, featuring cultural spaces, housing and offices on former port land around maritime-inspired heritage, can also be found in the other big port cities in Belgium and the Netherlands. Antwerp’s waterfront redevelopment around Het Eillandje and the restoration of some of the buildings of the Red Star Line, a passenger line founded in 1871 which carried migrants to the United States, are discussed in the contribution by Filip Smits and Johan Veekman.

Rotterdam’s Hotel New York, Holland-Amerika Lijn / Hotel New York, A.J. van der Wal. (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b0/Hotel_New_York%2C_Rotterdam%2C_ex_headquarter_of_Holland-America_Line-8384.jpg)

Rotterdam’s waterfront redevelopment Kop van Zuid follows a similar pattern. It transformed abandoned port areas across the river from the inner city and became accessible to the city through the construction of the Erasmus bridge, which opened in 1996. The Wilhelmina Pier and the Rijnhaven are home to carefully restored historic buildings. The Hotel New York, for example, was the former headquarters of the Holland America Line, and served as a hotel for migrants on their way the United States. It has been a national monument since 2000. Carefully restored, it still serves as a hotel today. Several old warehouses in the vicinity, such as Pakhuismeesteren and Santos (discussed by Wijsman/Kooiman) have also been restored.

The area’s vicinity to the cruise ship terminal and proximity to the city center make the area attractive for development. Other sites, further away from the city center, have also been redeveloped over the last years, including the buildings of the former shipbuilding company RDM (Rotterdamsche Droogdok Maatschappij). A group of architectural historians (Crimson) assessed the buildings and historical elements of the RDM to guide the renovation of each building. A group of buildings on the RDM site were already in the process of becoming a registered national monument. Since 2009, the renovated central machine hall and the former head office have hosted educational institutions [3]. The RDM Campus now aims to connect research, education and start-ups, with the goal of educating specialised technical workers; it promises to attract other tenants to the area. Many other parts of the Rotterdam port are also undergoing transformation, including the M4H area (Merwevierhavens), which is emerging as a hub for the makers industry [4].

Rotterdam has more to offer than the already well-published cases. The case of Schiedam, discussed by Bart Heinz, is particularly intriguing as there the renovation of historical buildings, and the creation of new buildings with a historical mantle, has gone hand-in-hand with a renewed use of the site for port activities. In Schiedam long-term connections from the site’s past into the future show another approach towards heritage preservation. Discovering the intrinsic economic development potential of the port area and connecting it with local financial and social interests helped revitalize an architectural jewel and establish a foundation for economic revitalization.

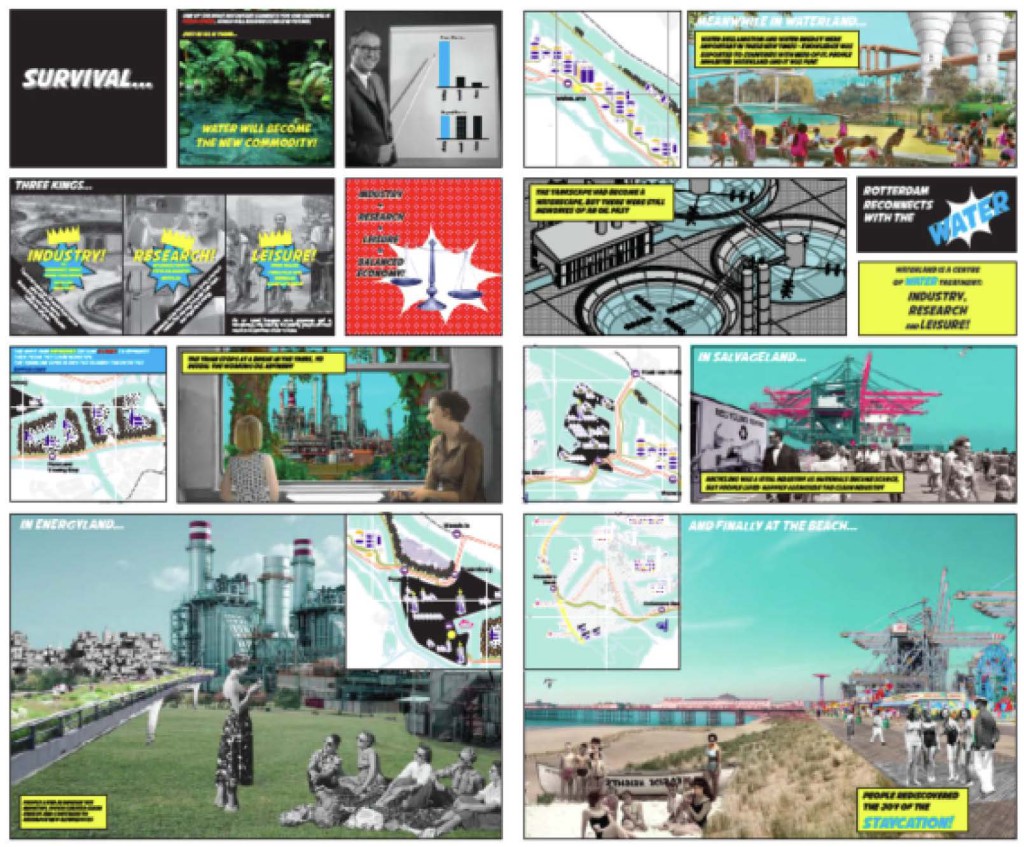

Design projects such as the ones included in the architectural design studio Architecture and Urbanism Beyond Oil by Olivia Forty and Deniz Üztem can help reflect on the challenges for future waterfronts.

In many areas, water and harbour infrastructure now serve as an attraction for leisure-related activities and urban development, with water-related heritage and remnants providing a glimpse of the past. The redevelopment of buildings with a history, sometimes several hundred years old, has been part of a range of solutions to challenges posed by old ports. The economic value of such transformations still merits further study. Heritage preservation is often considered expensive, but the positive financial impact on the surrounding neighbourhood is often ignored. Furthermore, new challenges are arising for waterfront renewal. We will have to find new approaches for the heritage of the future, the to-be-abandoned areas of ports that are far away from historical centres that attract tourists and citizens-the waterfronts linked to suburban or rural spaces. We also need solutions for petroleum-related infrastructures, the refineries, storage tanks, giant cranes and pipelines that occupy hundreds of hectares. Cleaning up heavily polluted sites and deciding which buildings have heritage value as an aesthetic or a historical object will require new strategies, technologies and values in line with the energy, social and technological transition. We need to decide whether these spaces are right for urban expansion or whether there are other, creative ways to use them as facilitators for the ports of the future.

Notes

[1] https://www.amsterdamtips.com/ndsm-wharf-amsterdam;

http://www.evadeklerk.com/en/ndsm-werf/

[2] https://nltimes.nl/2018/11/30/tonys-chocolonely-heading-zaandam-chocolate-factory-roller-coaster

[3] Vries, Isabelle M.J. 2014. “From Shipyard to Brainyard The redevelopment of RDM as an example of a contemporary port-city relationship.” In Port-City Governance, edited by Alix et al, 107-126.

[4] https://www.rotterdammakersdistrict.com/

Head Image: The National Shipping Museum Amsterdam with the reconstruction of Amsterdam, a ship of the VOC. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amsterdam_(VOC_ship)#/media/File:Replica_VOC-schip_Amsterdam.jpg)