“Riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodious vicus of recirculation to Howth Castle and environs – from James Joyce, Finnegans Wake”

If the opening lines of Finnegan’s Wake offer a vivid pen-picture of the confluence of Dublin’s River Liffey and the majesty of Dublin Bay (Fig. 1 & 2), Joyce’s famous boast “that if Dublin was ever destroyed the city could be reconstructed from the pages of Ulysses” – could hardly be sustained. His protagonist/alter ego Stephen Dedalus, would have considerable difficulty in reconciling the silhouette of Dublin Port and its historical Docklands in June 1904 with the transformed city of 2013. This article attempts to synopsise the context in which this dramatic transformation occurred, under the remit of the Dublin Docklands Development Authority, which was established in 1997, but which is scheduled to be terminated in November 2013, with its powers reverting to Dublin City Council.

Fig. 1 The Docklands in their urban context.

Fig. 1 The Docklands in their urban context.

Fig. 2 View of Dublin Bay.

Fig. 2 View of Dublin Bay.

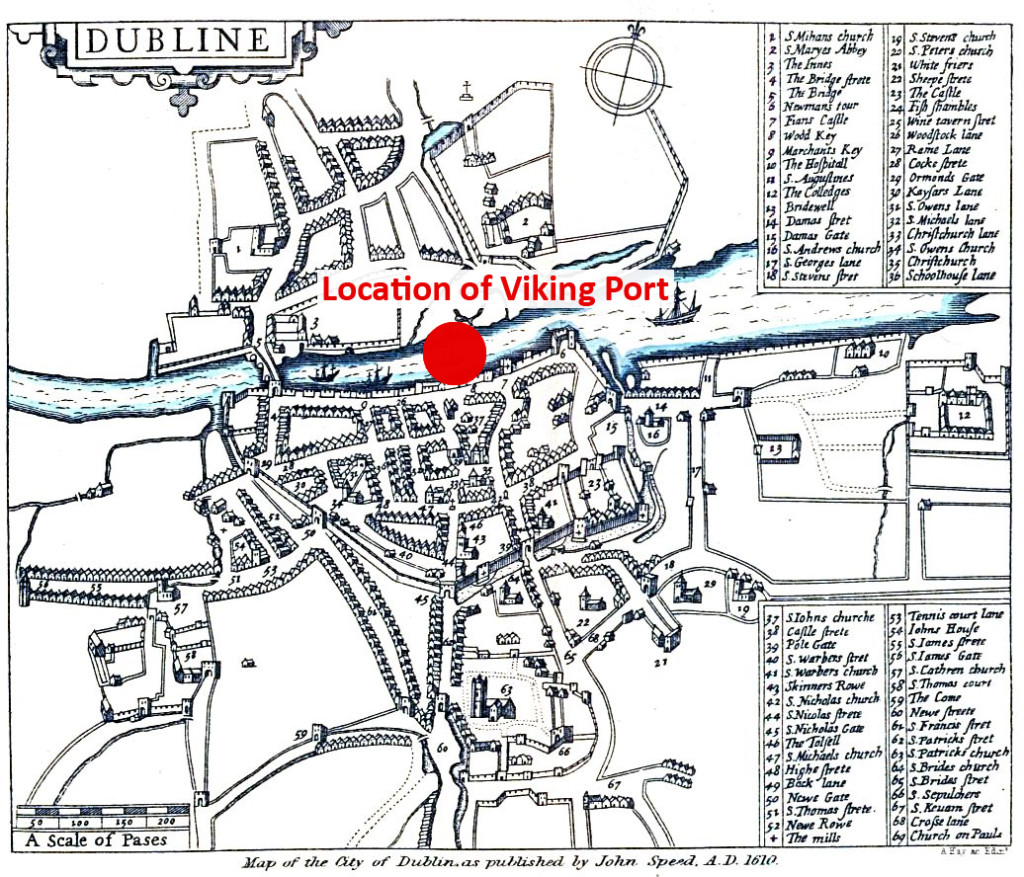

Dublin Port’s origins centre on the “Viking” settlement at Wood Quay, now the seat of civic administration, and the epicentre of the Medieval City, of which only fragments remain (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Dublin in 1610, by John Speed copy.

Fig. 3 Dublin in 1610, by John Speed copy.

The city of Joyce’s “Ulysses” was substantially the product of an extraordinary epoch of visionary expansionism by the elite minority “Anglo-Irish” who, while consolidating English conquest and rule over Ireland, enjoyed considerable autonomy for most of the 18th century, with its “Anglo-Irish” Parliament located in College Green.

This epoch saw the Port expand eastward, and with it the incremental reclamation of lands in the estuary of the River Liffey and the “canalisation” of the river itself (Fig. 4). This epoch also saw the construction of canals linking the colonial capital to the River Shannon, and the virtually inaccessible rural heartland of the island, one of which the Royal Canal, joined the river near the Custom House (Fig 5) while the Grand Canal, culminated in the elegant Grand Canal Basin (1796). The construction of the Great South Wall (1730 – 1790) (Fig. 6) which replaced an earlier wooden piled structure, was, one of the great marine engineering feats of its era. Its primary purpose was to provide adequate draught for shipping in Dublin Bay, which is intrinsically shallow and contains many hazardous sand banks. Following a survey by Captain Bligh (of “Mutiny on the Bounty” fame) in 1801, a counterpart “North Wall” was formed. These two engineering feats, to this day, define the entry for shipping to Dublin Port. Railways progressively superceded the canals, and linked the Port to the country’s interior from the 1840’s onwards. While Dublin was once the “Second City of the British Empire” with its Port economy reflecting British Imperial expansion, it went into progressive decline throughout the 19th century following the dissolution of the “Anglo Irish” Parliament in 1800.

Fig. 4 The River Liffey Meets, Dublin Port. ( © Peter Barrow )

Fig. 4 The River Liffey Meets, Dublin Port. ( © Peter Barrow )

Fig. 5 The Custom House, 1791. ( © Anew McKnight ).

Fig. 5 The Custom House, 1791. ( © Anew McKnight ).

Fig. 6 The Great South Wall, 1730-1790. ( © Leo Martin ).

Fig. 6 The Great South Wall, 1730-1790. ( © Leo Martin ).

Port activity was still a feature of Dublin City Centre into the 1970’s with cattle for export being herded through the streets, while the core economic activities were flour-milling and gas manufacture. The demise of these industries and the expansion of the “working” port eastwards, made former “port” land available for redevelopment.

Another portrait of Dublin in June 1904 would have revealed a city with an indigenous underclass, living in appalling poverty with economic diseases, which have been compared with contemporary Calcutta.

Following centuries of conflict, a new “Irish Free State” (1922), evolved from centuries of revolutionary anti-British resistance, and a bloody civil war. The “New State” had a strong rural ethos, with an antipathy to the country’s capital Dublin, seen as the historical bastion of “foreign” domination. The early decades of the new state were dominated by economic stagnation and emigration.

The inner-city Dublin and its historic port were in an advanced state of dereliction, decay when the Urban Renewal Acts (1985/86), sought to reverse continuing decay, by providing tax-incentives to investors in designated areas. Under this Act, the Custom House Docks Development Authority, focused on inducing investment into a former Dublin Port and Dock Company’s property for the first time in almost 2 centuries, by promoting an International Financial Services on the 10 ha. Custom House Docks site. This initiative resulted in the redevelopment of the site and indeed the beginning of a new epoch of economic growth, which inspired Government to expand its ambition to renew 527 ha of the “Docklands” under the aegis of the Dublin Docklands Development Authority. This Authority was empowered with the right to prepare masterplans, grant planning permission and invest in development projects, predicated on the principle of directing profits for such ventures to social regeneration. The linking of physical regeneration to social regeneration was a unique feature of the project, and for a decade at least of the DDDA’s existence, a significant social dividend resulted, as did a very significant transformation of the historic Docklands.

In addition to linking social regeneration to physical regeneration, plans from 1997 onwards, gave priority to use-mix, good urban design, and enhancement of the public realm.

Driven by the International Financial Services Centre, and related legal and corporate service providers, employment grew by 100% to over 40,000 in 10 years. Despite the economic collapse this figure remains stable, and is growing with the arrival of new Dublin “Docklands” entrants, e.g. Facebook, Google and the social media enterprises which have Global HQ’s in Dublin.

The regeneration of the historic docklands, while still very much a work in progress, and is progressively changing the “mental map” of Dublin City, particularly in the manner in which it has expanded the public realm. The North and South Banks of the Liffey, a prime generator of Dublin’s urban forum, have been attractively landscaped as generous pedestrian amenities, “Strategic” projects identified in the 1997 Masterplan, such as a National Convention Centre (Fig. 7), a major Performing Arts Venue, and a new College to offer “second chance” and life long learning opportunities have been delivered, as has a significant new transport and movement infrastructure, notably the extension of a tramway to the North Docks and 4 new bridge crossings. A planned metro/suburban rail/network rail inter-connector has been put on hold for economic reasons.

Fig. 7 Convention Centre and Samuel Beckett Bridge by Calatrava. ( © Michael Foley ).

Fig. 7 Convention Centre and Samuel Beckett Bridge by Calatrava. ( © Michael Foley ).

The social regeneration process, albeit very heavily dependent on funding generated from property development, has resulted in some impressive achievements, notably in education. In 1997, only 10% of “Docklands” young people, sat the Irish “Baccalaureate” (Leaving Certificate). In 2006 that figure was 60%. In 1997, less than 1% advanced to third level (university or similar education). That figure was 10% in 2006, with over 3,500 new houses being provided. Legally, 20% of new housing was specifically reserved for “social and affordable housing”.

Sadly, the board of the DDDA, became intoxicated with the prospect of joint-ventures in an over-heated market, to the extent that it became politically unsustainable, and is scheduled to cease to exist in November 2013. The planning functions will now revert to Dublin City Council.

The expansion and development of Dublin Port, reflects global patterns. From its origins in the 1700’s, as the “Ballast Office” it evolved as an essentially autonomous entity, as the “Dublin Port and Docks Company” to being incorporated in 1997 as a state entity – The Dublin Port Company. Today, the highly mechanised Port, is an essential “engine” of the Irish economy, which is very heavily reliant on its capacity to export goods and services. The Port handled over 24 million tonnes of cargo, and over 1.5 million passengers in 2003 and has a rapidly growing cruise ship business.

Historically the governance of the Port was beyond the remit of City Government. Its continuing expansion through land reclamation into Dublin Bay provoked considerable hostility.

A new governance regime has prepared a Masterplan (2012-40) which, while stating its own objectives, relates also to the Dublin City Development Plan.

This new culture is positive as the Dublin Port Company commits to initiatives that will engage with and integrate the Port area, with the city and Dublin Bay – which is an exceptionally beautiful resource, with unique recreational capacity and valuable national habitats and eco-systems.

Professor Eric Van Hooydonk’s articulation of “Soft Values” in Sea Ports has provided an inspiring philosophical framework for the Dublin Port Company’s “Soft Values” Strategy (2013), which will progressively evolve in the years to come, with a distinct Dublin and Irish accent (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Extract from Soft Values Strategy Document.

Fig. 8 Extract from Soft Values Strategy Document.

Is there one lesson which can be learnt from this epoch of regeneration? One obvious lesson is that a reliance on unsustainable liberal economic model to both drive a project and sustain it socially is not tenable.

Equally, there is clear evidence that a strong “plan-led” structure based on sustainable foundations, can at very least, mitigate the worst excesses of purely “market-led” development.

Hopefully, this epoch of change has created “critical mass” to attract and assure further inward investment, and that the next 20 years will vindicate the underlying planning principles which have informed the process to date.