We seem to be witnessing a growing spatial and ideological split between the heritage of historic urban ports and the actual working port facilities of those same cities. As containerization and logistics have transformed the operation of ports, as ships have gotten dramatically bigger, and as old shipyards have moved or closed, the day to day activities of busy ports have moved away from the historic cores of their host cities, leaving behind vast tracts of vacant waterfront land, shaped by colossal piers and docks, often highly polluted, and punctuated with hulking industrial sheds and gigantic insectile cranes and gantries. They have also left behind the cognate urban districts of warehouses, markets, bars, brothels and housing which were fed by the ports and their traffic. These leftovers, pathetic and picturesque in their semi-derelict state, have become the objects of nostalgia, scholarship, and neo-liberal urban redevelopment schemes. Along the way they are transformed into more or less authentic “heritage”, often by official local, national or even UNESCO designation, and thus become icons and indices of a rich history of maritime culture – a source of both local identity and depression. Meanwhile the ongoing port activity has moved elsewhere, often out of sight of the heritage area, but occasionally just across the way, as in Hamburg [1].

In any case, that literal gulf means that actual shipping is replaced by pleasure craft, commuter ferries and tourist boats, even cruise ships disgorging their thousands of camera-toting day trippers to consume ice cream and souvenirs in former warehouses. Very few cities wish to complicate that experience or the narrative that accompanies it by interweaving an account of the ongoing importance of port activity for local and global economic, social, cultural and environmental networks. Evidently the customers at high-end shopping malls in former shipyards have limited interest in where and how the goods they buy are designed, produced and travel to market. There are however a few places where port and maritime heritage of considerable age and interest still occupies the same geographic and economic space as contemporary port-related activity and industry. This is a brief case study of one such place, the Thames River estuary, not in the U.K., but in Connecticut, flanked by the cities of New London and Groton, and where a heritage-based plan explicitly included the contemporary economic, social, cultural and environmental life of those communities with all their challenges.

Shipyard 1862, Shanghai.

In May of 2015 the Yale Urban Design Workshop was approached by the board of the Avery Copp House Museum in Groton, Connecticut about advising them on the development of a strategic plan for expanding and sustaining the future role of the institution. The Avery Copp House is a small waterfront property dating to just after the American Revolution, of mainly local interest, with several family members still on the board, and like so many house museums around the United States, it faced declining visits and limited sources of funding. Early in the planning process, it became clear that on it’s own, the Avery Copp House had a less than bright future, but also that it was part of a community and region with dozens of buildings, institutions and sites, some of more than merely local interest and all part of an, as yet, unwritten and certainly uncoordinated and unpublicized narrative of the way in the which river and its port-related activity had shaped, and was continuing to shape, the life of the region. For example, just up the hill from the Avery Copp House is one of the best-preserved Revolutionary era forts on the east coast, Fort Griswold, the site of dramatic battle in 1781, itself not as well-known or visited as its interest and importance would suggest [2]. Just up the river, at the primary East Coast U.S. submarine base, is the Submarine Force Museum, the world’s largest collection of submarine artifacts and visited by more than 150,00 people each year (as opposed to 700 at the Avery Copp House), although most of them access the site directly off the highway and never even see the rest of historic Groton. At the high end of the heritage scale, and less than ten miles east, is the world-renowned Mystic Seaport Museum, where an entire seaport “village” consisting of 60 reconstructed and relocated historic buildings provides a setting for the most extensive maritime museum in the U.S., with a large collection of ships and boats, as well as craft and trade reenactments from rope-making to traditional shipbuilding. Mystic Seaport is visited by 250,000 people per year from all over the world (the adjacent Mystic Aquarium receives over 700,000 visitors), and while an enormous reservoir of tourists from which the New London-Groton area would like to draw, could not provide a more vivid contrast.

Avery Copp House Museum in Groton.

Fort Griswold and Battle Monument in Groton, with Electric Boat to the left, and Thames River, New London, and Fort Trumbull in the background.

While Mystic Seaport is purely heritage-based, although in the best and most engaging fashion, the Thames estuary is not, for example, simply home to a submarine museum, nor even a museum connected to an active naval submarine base. Since 1899 Groton has been home to Electric Boat (now owned by General Dynamics), the principal builder of submarines for the U.S. Navy, as well as other countries, employing nearly 10,000 workers in Groton, while across the river in New London some 3,000 engineers are designing the next generation of nuclear submarine, in a research facility abandoned in 2010 by pharma giant, Pfizer [3]. Whatever one thinks, or fears, of Electric Boat’s product, it is clear that port and maritime heritage in this case, enters directly into the current life, and livelihood of these communities, and that visitors are not merely, or mainly entertained by a retrospective experience. And this is far from the only case of the spatio-temporal network that has been sponsored by this port.

New London was, for much of the early nineteenth century, one of the three leading whaling ports, not just in North America, but in the world, along with Nantucket and New Bedford, Massachusetts, in a time when whale oil, not petroleum products, lit the lamps of the world [4]. That heritage is celebrated in the port in annual festivals that bring the “tall ships” of the world to the Thames, including reconstructed whalers, as well as the U.S. Coast Guard training barque Eagle, the only active duty tall ship in the Navy. Here again, the narrative is not simply retrospective, since the Eagle is a critical part of a rigorous training program – and therefore a familiar sight on the Thames – that is based just up the river at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, that has called New London home since 1876. In addition, plans are underway for the construction of a privately funded U.S. Coast Guard Museum to be sited on the waterfront directly across from New London’s historic H.H. Richardson train station, and in the midst of active ferry piers that take passengers to Fishers, Block, and Long Islands.

New London Harbor with cruise ship and Coast Guard barque Eagle.

Clearly, there is more than enough port and maritime heritage activity for the tiny Avery Copp House to be networked with, and once the planning process reached out to the boards and staff of these institutions, including the Coast Guard, the U.S. Navy and local governments, it was equally clear that there was a pent-up desire and demand for collective planning and collaborative management, programming and publicity at a regional level. What was equally clear was the almost belligerent commitment to tell the heritage story with a thoroughly contemporary angle that included more than the obvious, but elusive, economic development potential of heritage tourism. Local officials, businessmen, educators and ordinary citizens made the case to the planning team that they were not, given a history of disappointed hopes and investment in get-rich-quick schemes based on casinos or pharmaceuticals, interested in a simplistic and nostalgic approach to heritage-based planning.

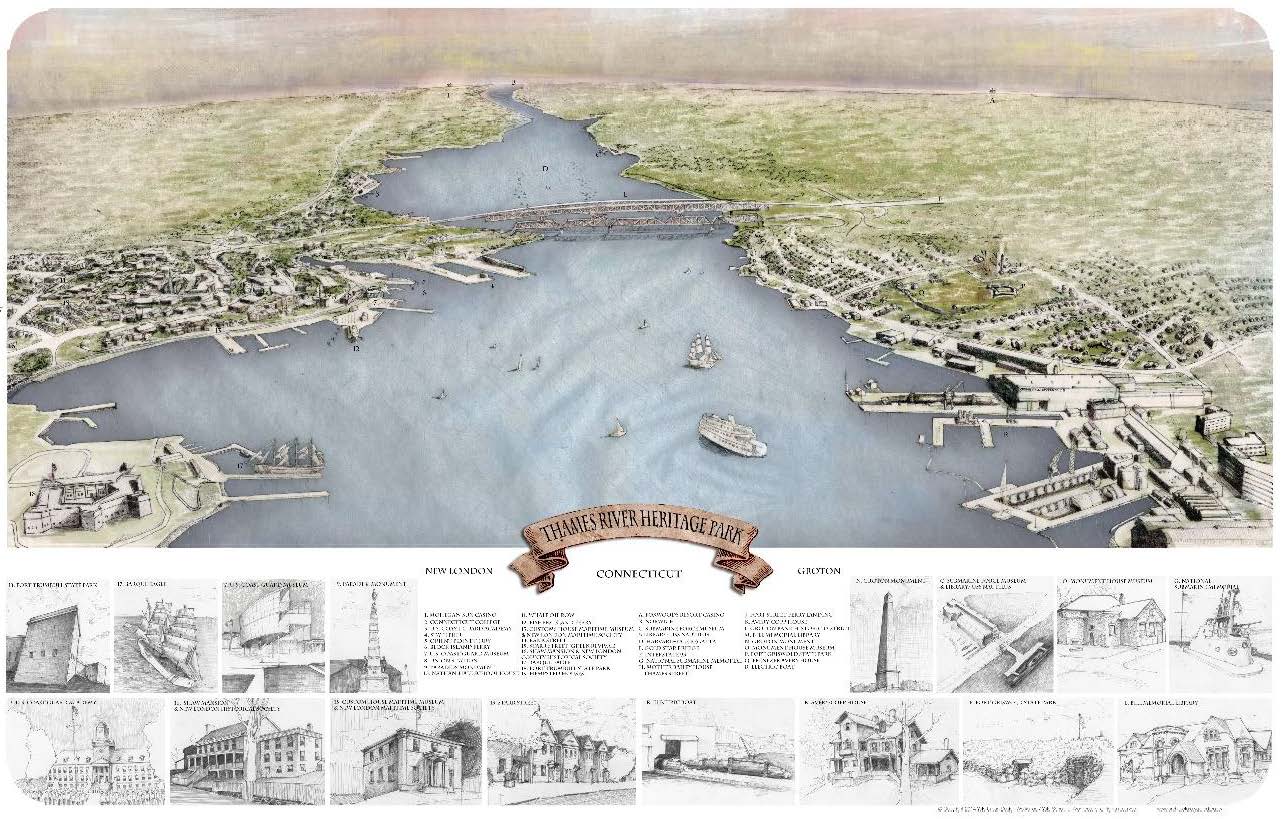

A galvanizing and catalytic moment in the planning process was the production of a contemporary drawing in the manner of a classic nineteenth century lithographic view that were produced for so many American cities, that showed all of the episodic elements of the Thames Estuary and port as part of one panoramic landscape: part of one shared public space that was the river itself. The team had been talking about somewhat exotic precedents like Hong Kong Harbour as the main public space of the city, but this brought the point home, so to speak. Not only was the river now clearly seen a sort of cultural and economic commons for its adjacent communities, the immediacy of visual and spatial relationships that tied the region together was recognized as potentially available and accessible by more than just heavy, fixed-path infrastructure like railroads and highways.

Thames River Heritage Park, Yale Urban Design Workshop.

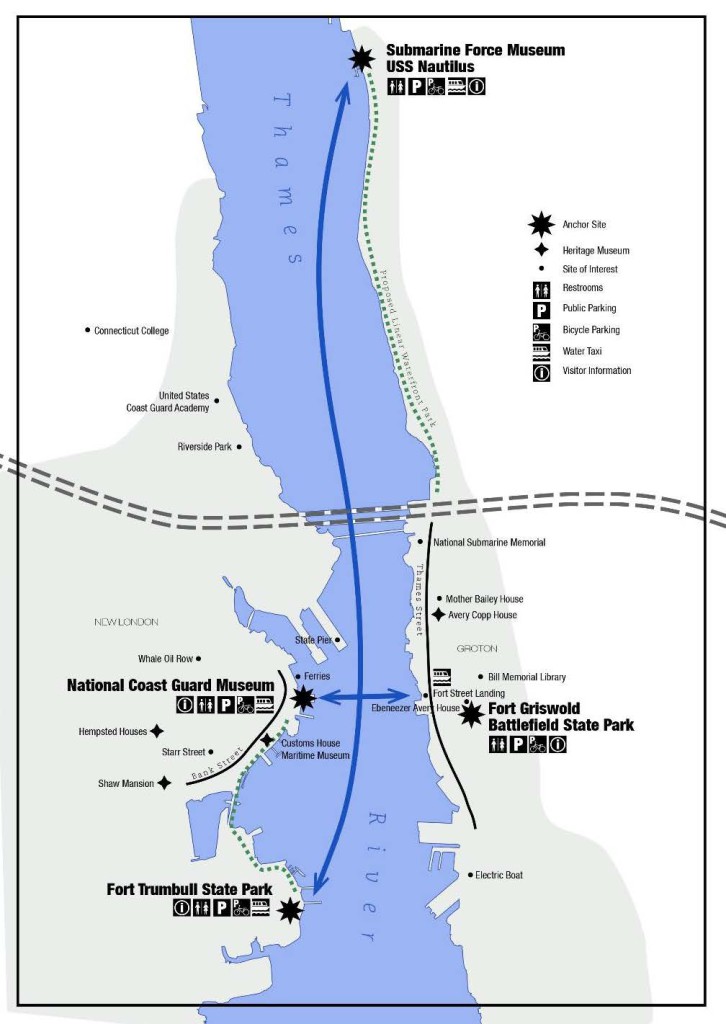

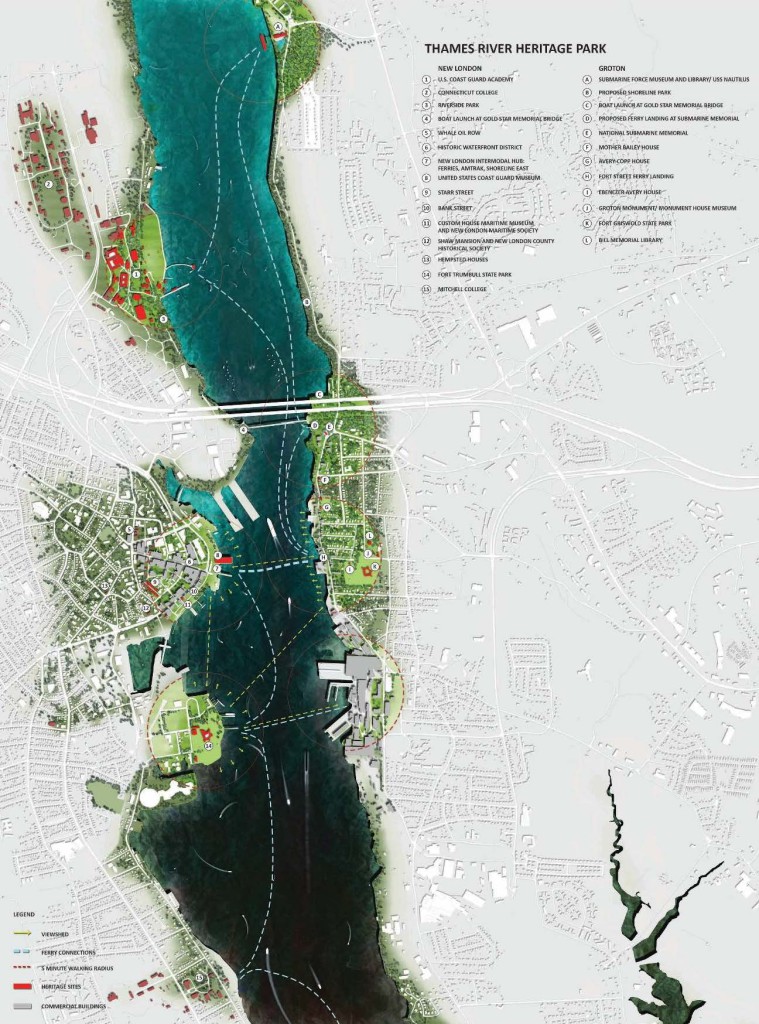

The next breakthrough involved the realization that, given the collection of hitherto largely autonomous institutions, the remarkable of intermodality of the region’s quite good, at least by American standards, transit system, and the general accessibility of the Thames waterfront, the structuring of a spatial and operational strategy for Connecticut’s first “Heritage Park,” would not demand heavy initial investment. In fact, in the day and age of social media and hand-held devices, even a formal “visitor’s center” could at least be postponed, if not bypassed altogether. The relatively modest start up strategy involved a water taxi, at first simply operating between New London and Groton, but eventually lacing up the river in a dense network of routes connecting and cross-referencing multiple sites, supplemented by a graphics program of informational and directional signage and publicity. In this regard, the project developed much like a small-scale version of Peter Ueberoth’s plan for the 1982 Los Angeles Summer Olympic Games, utilizing existing venues and facilities within the L.A. region, and employing graphic designers and public artists, rather than architects and builders [5].

Thames River Heritage Park, concept diagram, Yale Urban Design Workshop.

Thames River Heritage Park, overall plan, Yale Urban Design Workshop.

The Thames River Heritage Park and its water taxi service were inaugurated in the summer of 2016, they are still up and running. The taxi is enhanced now by on board narration, supplementing the visual and spatial experience of the port with a more literal story told to visitors and residents alike about their shared public space and heritage.

Thames River Heritage Park, water taxi service.

Notes

[1] This is now a fairly familiar story, allowing for the specificity of site and circumstances in particular cities. See for example, John Pendlebury, “The Historic Urban Landscape of the Liverpool Waterfront: The Three Graces in a New Perspective”, Waterfronts Revisited: European Ports in a Historic and Global Perspective, Heleni Porfyriou and Marichela Sepe, eds., Routledge, 2017; or Carola Hein, “Hamburg’s Port Cityscape: Large-scale urban transformation and the exchange of planning ideas”, Port Cities: Dynamic Landscapes and Global Networks, Routledge, 2011. On the historical process of rise, decline and redevelopment of ports worldwide, see Han Meyer, City and Port: Urban Planning as a Cultural Venture in London, Barcelona, New York, Rotterdam: changing relations between public urban space and large-scale infrastructure, International Books, 1999.

[2] See Eric D. Lehman, Homegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New London, Wesleyan University Press, 2014.

[3] Jeffrey L. Rodengen, The Legend of Electric Boat, Write Stuff Enterprises, 2006.

[4] Robert Owen Decker, The Whaling City: A History of New London, The Pequot Press, 1976.

[5] See Ed Mitchell, “They’re All Gone,” Perspecta 34, MIT Press, 2003.

Head image: Electric Boat, the principal builder of submarines for the U.S. Navy, with home in Groton since 1899.