╔

Ciudades portuarias y pluralidad lingüística en el Caribe centroamericano: Historia, poder y resistencia de Belice, Bluefields y Puerto Limón

Introducción

Introduction

Las bahías del Caribe centroamericano en el siglo XVI funcionaban como espacios estratégicos de articulación entre economías coloniales emergentes. En estos puntos de acceso, navíos británicos fondeaban, mientras pequeñas embarcaciones transportaban mercancías hacia la costa. En los improvisados embarcaderos, comerciantes miskitos intercambiaban maderas preciosas, así como marineros africanos compartían relatos en lenguas que apenas comenzaban a estructurarse.

Las ciudades portuarias del Caribe centroamericano constituyen un fenómeno singular en la historia lingüística de las Américas. En estos espacios, el contacto intercultural no produjo una simple hegemonía lingüística, sino la emergencia de sistemas híbridos, que reflejan la complejidad de las relaciones comerciales, políticas y sociales en la región.

Este artículo examina la transformación de estos enclaves marítimos desde sus orígenes como puestos de avanzada colonial, hasta su papel actual en centros de diversidad lingüística y cultural, desde tres ejemplos en mención. En este proceso, las ciudades han sido escenario de luchas discursivas en torno a la legitimidad de los idiomas locales, revelando dinámicas de poder que subyacen en las prácticas lingüísticas contemporáneas.

In the 16th century, Central American Caribbean bays functioned as strategic spaces of articulation between emerging colonial economies. At these access points, British ships anchored, while small boats transported goods to the coast. On the improvised piers, Miskito traders exchanged precious woods, just as African sailors shared stories in languages that were just beginning to take shape.

The port cities of the Central American Caribbean constitute a unique phenomenon in the linguistic history of the Americas. In these spaces, intercultural contact did not produce a simple linguistic hegemony, but the emergence of hybrid systems, which reflect the complexity of commercial, political and social relations in the region.

This article examines the transformation of these maritime enclaves from their origins as colonial outposts to their current role as centers of linguistic and cultural diversity, based on three examples. In this process, cities have been the scene of discursive struggles around the legitimacy of local languages, revealing power dynamics that underlies contemporary linguistic practices.

El mosaico colonial: Formación de los enclaves portuarios (1502-1821)

The Colonial Mosaic: Formation of Port Enclaves (1502-1821)

La historia colonial de Centroamérica se caracteriza por una dicotomía estructural: mientras la costa del Pacífico se consolidaba bajo el control administrativo del imperio español, la costa caribeña operaba con una autonomía relativa, moldeada por la influencia británica, tras la toma de Jamaica en 1655. Esta configuración divergente generó efectos duraderos en la organización sociolingüística de la región.

En el Pacífico, la administración colonial centralizada promovió una homogeneización lingüística basada en el castellano. En contraste, además de la flexibilidad administrativa, el aislamiento debido a dificultades de acceso, el abandono por parte de los incipientes estados nacionales y otros factores estructurales permitieron la coexistencia de múltiples lenguas y tradiciones culturales. La ausencia de una burocracia imperial rígida además facilitó la emergencia de zonas de contacto multilingües en las que diversas comunidades pudieron desarrollar sistemas comunicativos propios.

El caso de Belice City ilustra esta dinámica. Hacia 1650, los campamentos madereros británicos coexistían con mercados indígenas, generando un espacio donde los idiomas locales adquirían funciones pragmáticas en el comercio.

De manera similar, Bluefields en Nicaragua, fundada como refugio del pirata holandés Abraham Blauvelt en 1602, evolucionó hasta convertirse en la capital del protectorado británico de la Mosquitia. También, en 1849, los misioneros moravos alemanes consolidaron el uso del criollo local en su labor evangelizadora, asegurando su permanencia como lengua de comunicación intercomunitaria.

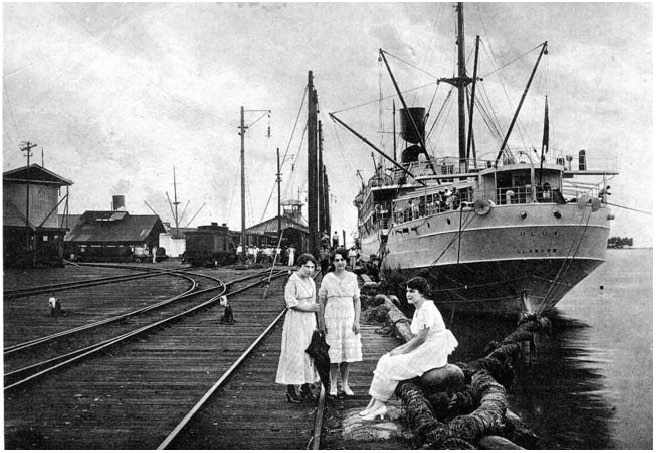

En el caso de Puerto Limón en Costa Rica, la configuración urbana estuvo directamente vinculada con las dinámicas migratorias. Aunque Cristóbal Colón avistó la zona en 1502, su relevancia portuaria solo se estableció a partir de 1865, con su designación oficial como puerto principal. La llegada de trabajadores jamaiquinos en 1872 y la construcción del ferrocarril en 1890 propiciaron un entorno lingüístico en el que el mekatelyu se convirtió en un marcador de identidad y resistencia cultural.

Colonial history of Central America is characterized by a structural dichotomy: while the Pacific coast was consolidated under the administrative control of the Spanish empire, the Caribbean coast operated with relative autonomy, shaped by British influence; specially, after the capture of Jamaica in 1655. This divergent configuration generated lasting effects on the sociolinguistic organization of the region.

In the Pacific, the centralized colonial administration promoted a linguistic homogenization based on Spanish. In contrast and in addition to administrative flexibility, isolation due to access difficulties, abandonment by the incipient national states and other structural factors allowed the coexistence of multiple languages and cultural traditions. The absence of a rigid imperial bureaucracy also facilitated the emergence of multilingual contact zones in which diverse communities were able to develop their own communication systems.

The case of Belize City illustrates this dynamic. By 1650, British lumber camps coexisted with indigenous markets, creating a space where local languages took on pragmatic functions in trade.

Similarly, Bluefields in Nicaragua, founded as a refuge for the Dutch pirate Abraham Blauvelt in 1602, evolved to become the capital of the British protectorate of the Mosquitia. Also, in 1849, German Moravian missionaries consolidated the use of local Creole in their evangelizing work, ensuring its permanence as a language of intercommunity communication.

In Puerto Limón in Costa Rica, the urban configuration was directly linked to migratory dynamics. Although Christopher Columbus sighted the area in 1502, its port relevance was only established from 1865, with its official designation as a main port. The arrival of Jamaican workers in 1872 and the rail construction in 1890 fostered a linguistic environment in which Mekatelyu became a marker of identity and cultural resistance.

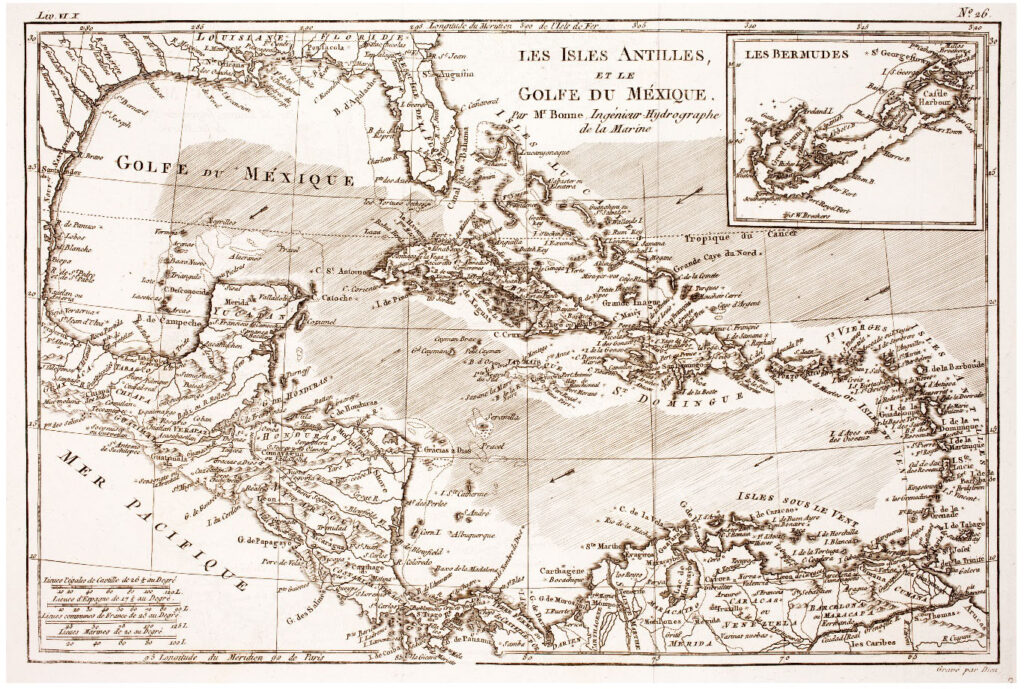

Mapa de las Antillas y el Caribe, elaborado por Rigobert Bonne para el “Atlas de toutes les parties connues du globe terrestre” (1780). (Fuente: Wikimedia Commons, dominio público).

Map of the Antilles and the Caribbean, created by Rigobert Bonne for the “Atlas de toutes les parties connues du globe terrestre” (1780). (Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

La ecología lingüística portuaria

The Linguistic Ecology of Ports

El paisaje lingüístico de estas ciudades es un testimonio de la convergencia de múltiples procesos históricos. Por ejemplo, los Garífunas, desplazados de San Vicente en 1797, introdujeron una lengua que sintetizaba influencias arahuacas, caribes y africanas. Paralelamente, las interacciones con piratas y comerciantes holandeses y franceses, durante los siglos XVII y XVIII, dejaron rastros lingüísticos en las jergas marítimas locales que, fueron incorporadas en los criollos emergentes. En el siglo XIX, los moravos desempeñaron un papel central en la estandarización de los idiomas locales, facilitando su incorporación a prácticas religiosas y educativas.

The linguistic landscape of these cities is a testimony to the convergence of multiple historical processes. For example, the Garifuna, displaced from St. Vincent in 1797, introduced a language that synthesized Arawak, Carib, and African influences. At the same time, interactions with pirates and Dutch and French merchants during the 17th and 18th centuries left linguistic traces in local maritime jargons that were incorporated into the emerging creoles. In the 19th century, the Moravians played a central role in the standardization of local languages, facilitating their incorporation into religious and educational practices.

Muelle de la United Fruit Company, Puerto Limón, Costa Rica, inicios del siglo XX. (Fuente: Historia UNED, ‘Estampas de antaño’, Repositorio Digital de la Universidad Estatal a Distancia de Costa Rica).

United Fruit Company dock, Puerto Limón, Costa Rica, early 20th century. (Source: Historia UNED, ‘Estampas de antaño’, Digital Repository of the Universidad Estatal a Distancia de Costa Rica).

Las ciudades portuarias en la actualidad

Port Cities Today

En el siglo XXI, estas ciudades enfrentan nuevas tensiones lingüísticas derivadas de procesos de globalización y homogeneización cultural. Belice City ha experimentado un ascenso del criollo beliceño a una posición de prestigio dentro del ámbito comunicativo. En Bluefields, programas bilingües buscan equilibrar la enseñanza del criollo nicaragüense con las demandas de un sistema educativo formalmente estructurado en español. En Puerto Limón, el mekatelyu es reivindicado como un elemento central de la identidad costarricense, aunque su uso sigue siendo periférico para los ámbitos institucionales.

In the 21st century, these cities face new linguistic tensions arising from processes of globalization and cultural homogenization. Belize City has experienced a rise of Belizean Creole to a position of prestige within the communicative sphere. In Bluefields, bilingual programs seek to balance the teaching of Nicaraguan Creole with the demands of a formally structured educational system in Spanish. In Puerto Limón, Mekatelyu is claimed as a central element of Costa Rican identity, although its use remains peripheral to institutional settings.

Músicos caribeños interpretando música tradicional con tambores, representando la rica herencia cultural y musical de la región. (Fuente: Randall Ruiz en Pexels, licencia gratuita).

Caribbean musicians performing traditional music with drums, representing the rich cultural and musical heritage of the region. (Source: Randall Ruiz on Pexels, free license).

Sin embargo, estos espacios también están sujetos a presiones que amenazan la vitalidad de sus lenguas tradicionales. La predominancia de las lenguas nacionales en los sistemas educativos, el avance del turismo masivo y los procesos de modernización portuaria han generado una reconfiguración del uso del espacio lingüístico, muchas veces en detrimento de las formas locales de comunicación.

However, these spaces are also subject to pressures that threaten the vitality of their traditional languages. The predominance of national languages in educational systems, the advance of mass tourism and port modernization processes have generated a reconfiguration of the use of linguistic space, often to the detriment of local forms of communication.

Transformación portuaria y nuevas dinámicas urbanas

Port Transformation and New Urban Dynamics

Las ciudades portuarias del Caribe centroamericano han sido objeto de una reestructuración funcional que las ha situado en la intersección entre el comercio global y la industria turística. La coexistencia de puertos industriales con terminales de cruceros ha generado una diferenciación entre los espacios destinados a la actividad económica y aquellos orientados al consumo turístico.

The port cities of the Central American Caribbean have been subject to a functional restructuring that has placed them at the intersection between global trade and the tourist industry. The coexistence of industrial ports with cruise terminals has generated a differentiation between spaces destined for economic activity and those oriented towards tourist consumption.

Vista actual de un puerto modernizado en el Caribe centroamericano, evidenciando la coexistencia entre la infraestructura contemporánea y los elementos culturales tradicionales.

Current view of a modernized port in the Central American Caribbean, evidencing the coexistence between contemporary infrastructure and traditional cultural elements.

Belice City ejemplifica esta transformación mediante la segmentación entre la ‘ciudad turística’ y la ‘ciudad local’, lo que ha propiciado la emergencia de nuevos registros lingüísticos orientados a la comunicación con visitantes extranjeros. En Puerto Limón, la tensión entre su función histórica como puerto comercial y su creciente integración en la industria de cruceros ha generado fricciones en el tejido urbano. En Bluefields, los planes de modernización portuaria plantean desafíos para la conservación de sus barrios históricos y sus prácticas lingüísticas tradicionales.

Belize City exemplifies this transformation through the segmentation between the ‘tourist city’ and the ‘local city’, which has led to the emergence of new linguistic registers oriented towards communication with foreign visitors. In Puerto Limón, the tension between its historical function as a commercial port and its growing integration into the cruise industry has generated friction in the urban fabric. In Bluefields, port modernization plans pose challenges for the conservation of its historic neighborhoods and traditional linguistic practices.

Conclusiones

Conclusions

Las ciudades portuarias del Caribe centroamericano no pueden reducirse a meros nodos comerciales. Son espacios donde las luchas por la representación lingüística y cultural han moldeado su desarrollo histórico. Su evolución demuestra que las identidades lingüísticas no son simples vestigios del pasado, sino formaciones discursivas activas, que emergen en la intersección de múltiples procesos históricos, económicos y políticos.

El estudio de estas ciudades permite comprender cómo la resistencia lingüística no solo es una cuestión de preservación cultural, sino un mecanismo de negociación simbólica en sociedades marcadas por jerarquías de poder y exclusión. En este sentido, la diversidad lingüística no es una anomalía dentro del desarrollo moderno, sino un testimonio de la agencia de las comunidades que han hecho de estos espacios su hogar.

Port cities in the Central American Caribbean cannot be reduced to mere commercial nodes. They are spaces where struggles for linguistic and cultural representation have shaped their historical development. Their evolution shows that linguistic identities are not simple vestiges of the past, but active discursive formations, emerging at the intersection of multiple historical, economic, and political processes.

The study of these cities allows us to understand how not only a matter of cultural preservation is linguistic resistance. It is a mechanism of symbolic negotiation in societies marked by hierarchies of power and exclusion. In this sense, linguistic diversity is not an anomaly within modern development, but a testimony to the agency of the communities that have made these spaces their home.

IMAGEN INICIAL | Vista del puerto modernizado de Belice en el Caribe Centroamericano.