╔

Planificar el borde marítimo: Treinta años de integración puerto-ciudad en Málaga

Ofrecer una lectura narrada de la integración reciente del Puerto de Málaga en la ciudad no es tarea sencilla. La relación puerto‑ciudad es, por definición, un tejido de equilibrios inestables entre eficiencia logística, calidad urbana y sostenibilidad ambiental. En Málaga, además, este diálogo se produce en un enclave particularmente sensible: un puerto histórico inserto en el corazón metropolitano, encajado entre el cauce del Guadalmedina, las laderas de Gibralfaro y un frente litoral ya consolidado. Para comprender su alcance conviene situar el cambio de paradigma que introduce el PGOU de 1983: desde ese momento el recinto portuario deja de concebirse como un ámbito autónomo y pasa a considerarse pieza indisoluble de la estructura urbana, con objetivos explícitos de compatibilidad paisajística, ambiental y funcional y con la encomienda de un Plan Especial capaz de traducir ese giro en determinaciones operativas.

Offering a narrated reading of the recent integration of the Port of Málaga into the city is no simple task. The port–city relationship is, by definition, a web of unstable balances between logistical efficiency, urban quality and environmental sustainability. In Málaga, this dialogue also unfolds in a particularly sensitive setting: a historic port embedded in the metropolitan core, wedged between the Guadalmedina River, the slopes of Gibralfaro, and an already consolidated seafront.To understand its scope, it is helpful to situate the paradigm shift introduced by the 1983 General Urban Development Plan (PGOU): from that point on, the port precinct ceased to be conceived as an autonomous realm and came to be considered an inseparable component of the urban structure, with explicit objectives of landscape, environmental and functional compatibility and the mandate for a Special Plan capable of translating that turn into operational determinations.

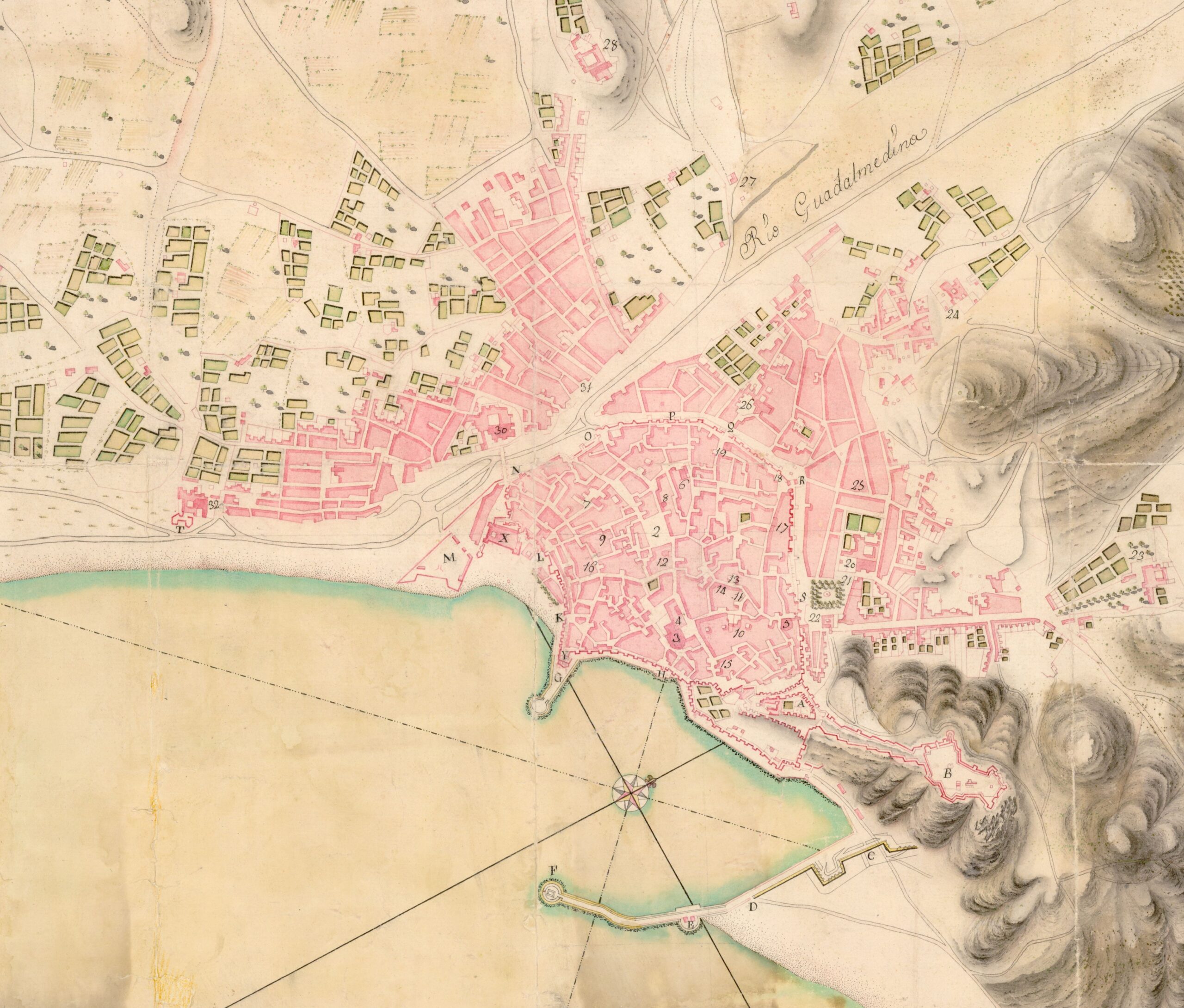

El Puerto de Málaga hacia 1750. Plano de la Plaza de Málaga. Ingenieros militares. (Fuente: Ministerio de Defensa. Centro Geográfico del Ejército).

The Port of Málaga around 1750. Plan of the Plaza of Málaga. Military engineers. (Source: Ministry of Defence. Army Geographic Centre).

Este texto sintetiza el proceso mediante el que la integración puerto‑ciudad se fue materializando durante las últimas décadas —planes, concursos, obras y pactos interadministrativos— y evalúa sus efectos sobre tres planos interdependientes: el espacio público (continuidades, accesos, calidad paisajística), la movilidad (gestión de flujos turísticos y logísticos, jerarquía viaria, intermodalidad) y la operativa portuaria (ampliación mar adentro, compatibilidades de uso, seguridad y eficiencia). A esa evaluación se suma una mirada cualitativa sobre la dimensión simbólica e identitaria de las transformaciones, consciente de que la integración no se agota en abrir muelles, sino que implica también integrar el relato portuario en la vida cotidiana de la ciudad.

No aspira a la exhaustividad —eso requeriría un estudio monográfico con levantamientos específicos, series de datos y evaluación de impacto a detalle—, sino a una síntesis razonada, apoyada en la documentación disponible y en la experiencia acumulada de proyectos y debates públicos. Desde esa base, el texto propone criterios de lectura para el público generalista, no necesariamente experto en la gestión portuaria y urbana. Se plantea por tanto una reflexión personal que busca extraer algunas claves del proceso, al tiempo plantear los principales retos a los que se aún debe enfrentar el Puerto de Málaga para lograr una integración plena en la ciudad en la próxima década.

This text synthesises the process by which port–city integration materialised over recent decades—plans, competitions, works and inter‑administrative agreements—and assesses its effects across three interdependent planes: public space (continuities, access, landscape quality), mobility (management of tourist and logistics flows, road hierarchy, intermodality) and port operations (seaward expansion, use compatibilities, safety and efficiency). To that assessment it adds a qualitative view of the symbolic and identity dimension of the transformations, mindful that integration is not exhausted by opening the quays but also entails integrating the port’s narrative into the city’s everyday life.

It does not aspire to exhaustiveness—this would require a monographic study with specific surveys, data series and detailed impact evaluation—but rather to a reasoned synthesis, supported by the available documentation and the accumulated experience of projects and public debate. On that basis, the text proposes reading criteria for a general audience not necessarily expert in port and urban management. It is therefore presented as a personal reflection that seeks to extract a number of key insights from the process while setting out the main challenges that the Port of Málaga must still face to achieve full integration into the city over the next decade.

El cambio de paradigma (1983–2000): primeros pasos para la apertura a la ciudad

The Paradigm Shift (1983–2000): First Steps Towards Opening to the City

En 1983 el Plan General de Ordenación Urbana, tras décadas sin un instrumento urbanístico que ordenará la planificación de la ciudad, decidió mirar el puerto como una pieza más de la estructura de la ciudad. Introdujo metas concretas como la necesaria conexión física y visual entre los muelles y el resto de la ciudad, con objeto de mejorar la accesibilidad entre estos y ordenar los límites portuarios. Objetivos que serían desarrollados por un Plan Especial, el cual debía articular la compatibilidad con el uso ciudadano sin menoscabo de la operativa marítima. Fue el punto de partida de un proceso largo, con idas y venidas, que aún hoy sigue en revisión y evolución.

In 1983, after decades without a planning instrument to guide the city’s development, the General Urban Development Plan decided to regard the port as yet another piece of the city’s structure. It introduced concrete goals such as the necessary physical and visual connection between the quays and the rest of the city, with a view to improving accessibility and ordering the port boundaries. These objectives were to be developed by a Special Plan, which was to articulate compatibility with civic use without undermining maritime operations. It was the starting point of a long process, with its ups and downs, that remains under review and evolving to this day.

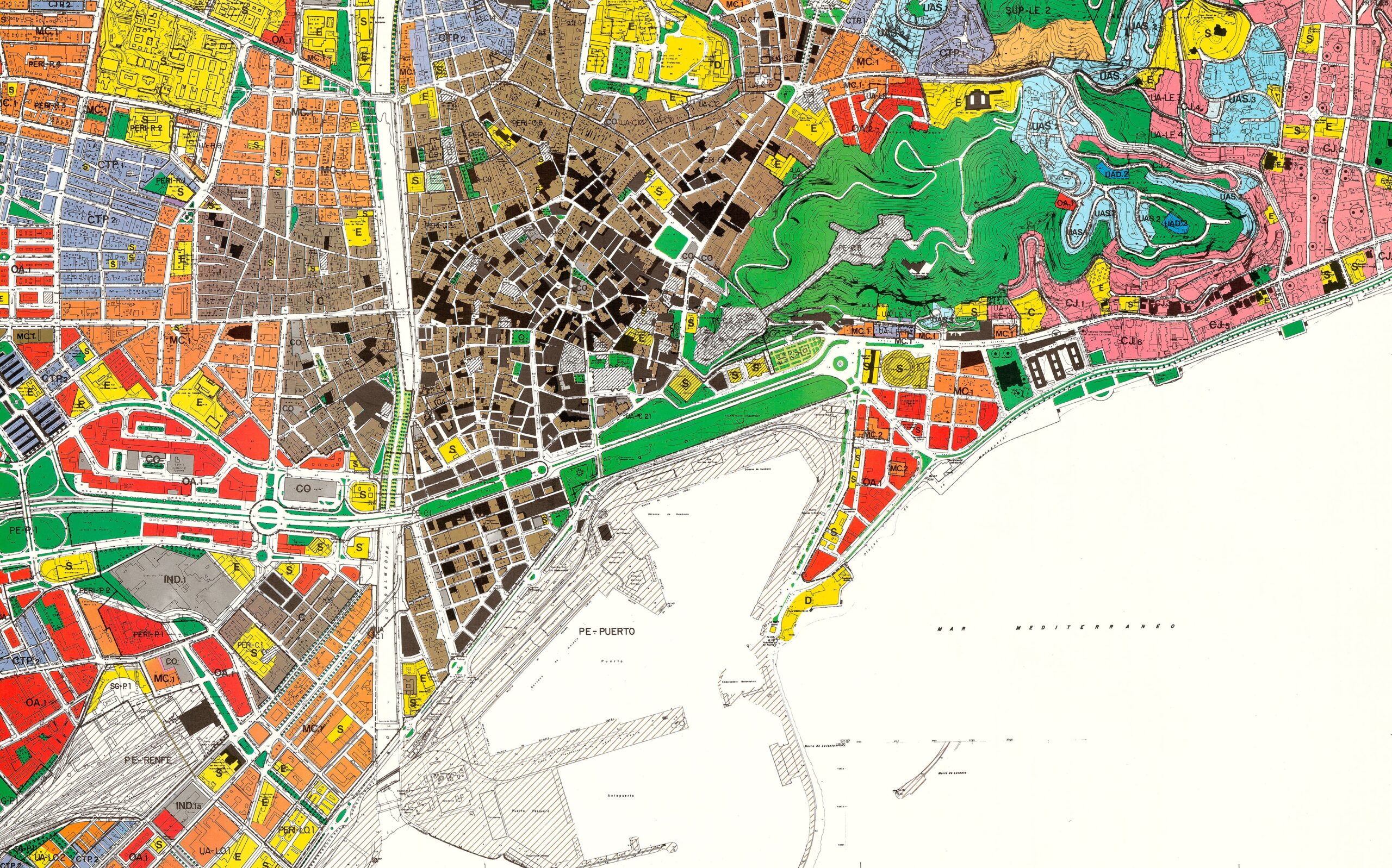

El Puerto de Málaga en el Plan General de Ordenación Urbana de 1983. (Fuente: Ayuntamiento de Málaga).

The Port of Málaga in the 1983 General Urban Development Plan. (Source: Málaga City Council).

Las primeras tentativas para reconfigurar los muelles 1 y 2 se cristalizaron en 1988, con una primera propuesta encargada por la Autoridad Portuaria, que sería descartada por el Ayuntamiento, dada la excesiva edificabilidad y altura de la edificación previstas en la proximidad al Centro Histórico. Lejos de enfriar el debate, esta primera iniciativa abrió paso a nuevas propuestas, también por parte del Ayuntamiento. En 1991, ambas instituciones encargaron conjuntamente el Avance del Plan Especial, que por primera vez colocó en un mismo documento dos vectores complementarios: por un lado, la expansión técnica del puerto (prolongación del dique de Levante, estación marítima y plataforma de contenedores); por otro, la apertura ciudadana del borde (conexión del muelle 2 con el Parque, una gran plaza en torno a La Farola y la permeabilidad del muelle 4 encajada con la cuadrícula del Ensanche Heredia). Esa dialéctica —crecer mar adentro y abrirse tierra adentro— guiaría buena parte de las decisiones de las décadas siguientes.

The first attempts to reconfigure Piers 1 and 2 took shape in 1988, with an initial proposal commissioned by the Port Authority, which was rejected by the City Council owing to the excessive development capacity and the building heights envisaged so close to the Historic Centre. Far from cooling the debate, this first initiative paved the way for new proposals, including from the City Council itself. In 1991, both institutions jointly commissioned the Initial Draft of the Special Plan which, for the first time, brought together in a single document two complementary vectors: on the one hand, the technical expansion of the port (extension of the Levante breakwater, a passenger terminal and a container terminal); on the other, opening the waterfront to the city (connecting Pier 2 with the Park, creating a large square around La Farola lighthouse, and introducing permeability at Pier 4 by stitching it into the Ensanche Heredia grid). That dialectic—pushing seaward while opening landward—would guide many of the decisions taken over the following decades.

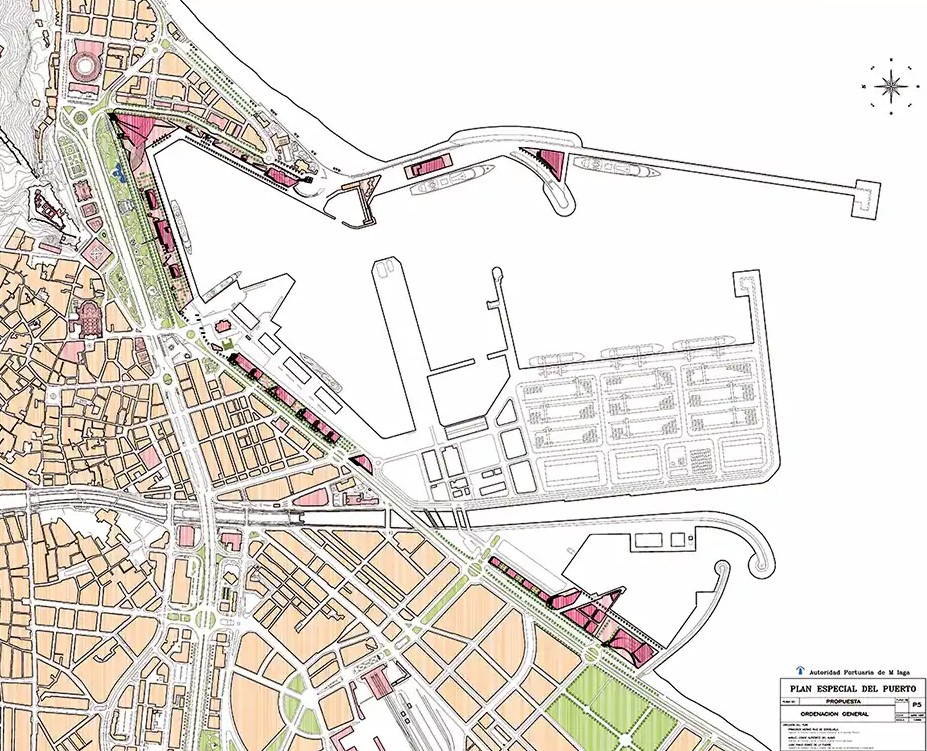

Propuesta del Ayuntamiento de Málaga para la integración puerto-ciudad. Antecedente del Avance del Plan Especial de 1991. (Fuente: Gerencia Municipal de Urbanismo de Málaga).

Proposal by Málaga City Council for port–city integration. Precursor to the 1991 Preliminary Special Plan. (Source: Málaga Municipal Urban Planning Authority).

La aprobación definitiva del Plan Especial en 1998 supuso un hito, con ajustes relevantes respecto al Avance. Se suprimió la torre terciaria prevista en la “esquina” de los muelles 1–2, se reservaron suelos estratégicos para la estación marítima y, en la plataforma de San Andrés, para un futuro auditorio; a cambio, se incrementó la edificabilidad comercial del muelle 2, con la consiguiente merma del palmeral inicialmente imaginado. A la complejidad técnica se sumó la administrativa: la entrada en juego de nuevas competencias autonómicas enfrió la aplicación inmediata del Plan y la convocatoria de una concesión para los muelles 1 y 2 —alejada de lo aprobado— activó una movilización ciudadana que terminaría reencauzando la operación.

The definitive approval of the Special Plan in 1998 marked a milestone, with significant adjustments relative to the Preliminary Draft. The tertiary tower envisaged at the “corner” of Quays 1–2 was removed; strategic land was reserved for the passenger terminal and, on the San Andrés platform, for a future auditorium; in exchange, commercial floor area on Quay 2 was increased, with the consequent reduction of the palm grove initially imagined. Administrative complexity compounded the technical challenges: the arrival of new regional competences slowed the immediate application of the Plan, and the launch of a concession for Quays 1 and 2—at odds with what had been approved—triggered a civic mobilisation that would ultimately put the operation back on track.

Plan Especial del Puerto de Málaga de 1998. Ordenación General. (Fuente: Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga).

1998 Special Plan for the Port of Málaga. General Layout. (Source: Málaga Port Authority).

Rompiendo los límites del puerto (2000–2025): expansión mar adentro y apertura tierra adentro

Breaking the Port’s Limits (2000–2025): Expansion Seaward and Opening Landward

Mar adentro, la prolongación del dique de Levante —que penetra casi un kilómetro en el Mediterráneo— y el muelle 9 configuraron una dársena exterior ampliada en torno a 400.000 m². Allí, los cruceros atracan al este y los portacontenedores operan al oeste, una convivencia funcional eficaz pero tensa que es consecuencia de un puerto cuyo crecimiento sólo puede producirse hacia el mar, con la costa urbana completamente consolidada.

Tierra adentro, la transformación de los muelles centrales cambió la experiencia ciudadana del frente marítimo. El muelle 1 se convirtió en un paseo de ocio y comercio de gran aceptación, mientras que el muelle 2 —el Palmeral de las Sorpresas— aportó calidad paisajística, dotaciones culturales y un corredor peatonal paralelo al Parque. Al mismo tiempo, la supresión parcial de verjas y la nueva disposición de pasos y estancias devolvieron a los malagueños la cotidianidad del puerto: pasear entre palmeras, asomarse a los atraques, detenerse a observar la maniobra de una terminal o el tránsito de una embarcación de recreo.

En este proceso cabe reconocer dos hitos que permitirían el viraje de las actuaciones desarrolladas hasta la fecha. Primero, se excluyó el muelle 2 de la concesión, y en 2000 se lanzó un concurso ajustado al Plan, con menor edificabilidad y usos acotados a cultura, restauración y estación marítima. De ahí nacería El Palmeral de las Sorpresas. Después, en 2004, un Protocolo entre Ayuntamiento y Autoridad Portuaria blindó la desaparición de volúmenes sobre rasante en el muelle 1 (salvo un lucernario de vidrio), consolidó cesiones culturales y precisó la parcela del auditorio en San Andrés. La revisión de 2010 incorporó ya el proyecto del Palmeral —en ejecución— y los cambios pactados en el muelle 1, preparando el salto de la planificación a la obra. Cambios que se incorporaron al Plan General de Ordenación Urbana de 2011.

Seaward, the extension of the Levante breakwater—projecting almost a kilometre into the Mediterranean—and Quay 9 configured an enlarged outer harbour basin of around 400,000 m². There, cruise ships berth to the east and container vessels operate to the west, an effective yet tense functional coexistence that stems from a port whose growth can only proceed towards the sea, with the urban coastline fully consolidated.

Landward, the transformation of the central quays changed citizens’ experience of the waterfront. Muelle 1 became a popular leisure‑and‑retail promenade, while Muelle 2—the Palmeral de las Sorpresas—contributed landscape quality, cultural facilities and a pedestrian corridor parallel to the Parque. At the same time, the partial removal of fencing and the new arrangement of crossings and places to linger returned the everydayness of the port to the people of Málaga: strolling among palm trees, looking out over the berths, pausing to watch a terminal operation or the passage of a pleasure craft.

Two milestones underpinned the shift in the actions carried out to date. First, Quay 2 was excluded from the concession, and in 2000 a competition aligned with the Plan was launched, with lower floor area and uses limited to culture, food and beverage, and the passenger terminal. From that process the Palmeral de las Sorpresas was born. Then, in 2004, a Protocol between the City Council and the Port Authority guaranteed the disappearance of above‑ground volumes on Quay 1 (save for a glass skylight), consolidated cultural allocations and specified the plot for the auditorium in San Andrés. The 2010 revision incorporated the Palmeral project—then under construction—and the agreed changes for Quay 1, preparing the leap from planning to works. Changes incorporated into the 2011 General Urban Development Plan.

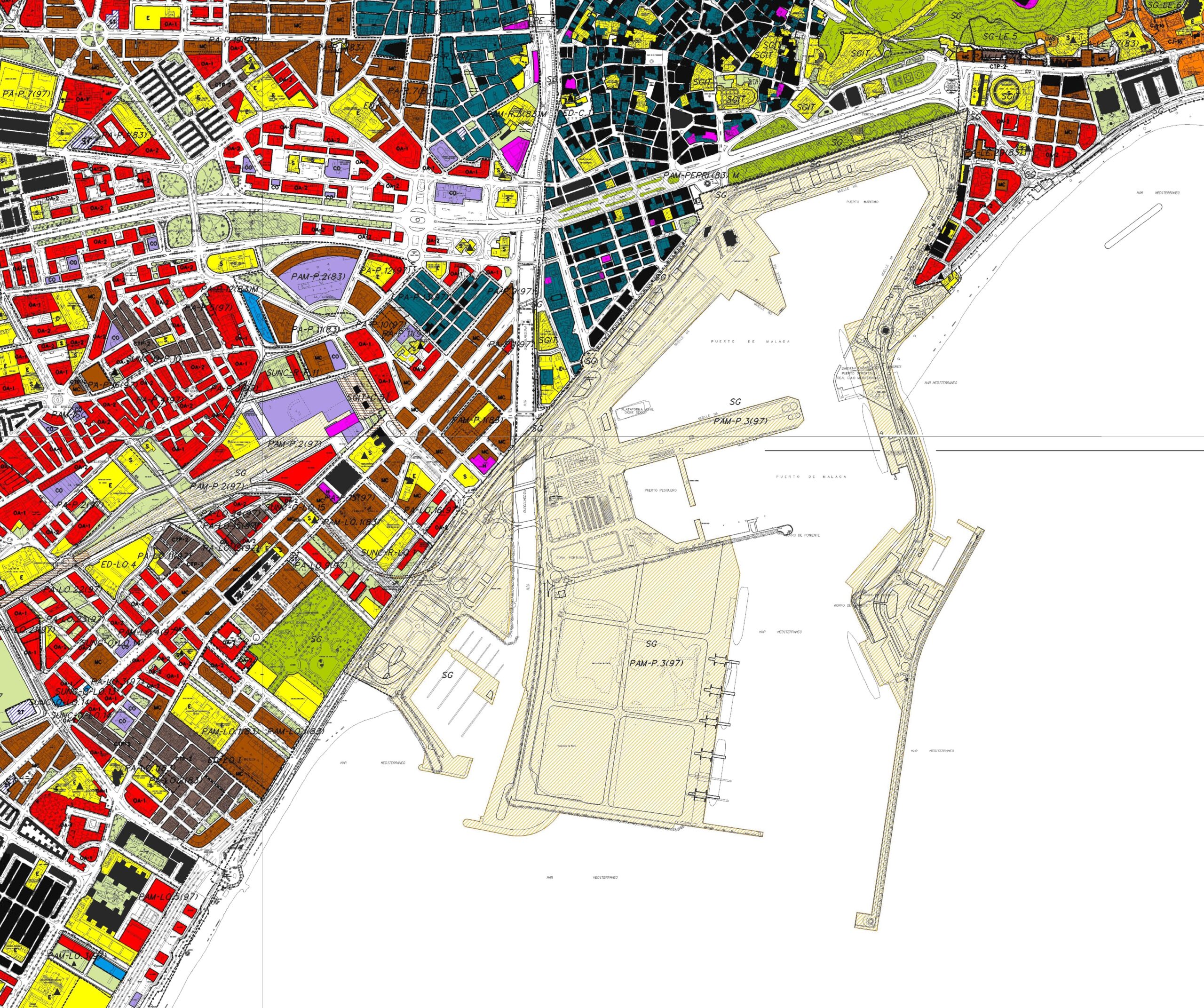

El Puerto de Málaga en el Plan General de Ordenación Urbana de 2011. (Fuente: Ayuntamiento de Málaga).

The Port of Málaga in the 2011 General Urban Development Plan. (Source: Málaga City Council).

Sin embargo, no todo fue según lo previsto. En el muelle 1, la lógica comercial restó impulso a la gran plaza en torno a La Farola y al deseado paseo balcón continuo en cubierta; en el muelle 2, la continuidad urbana se vio condicionada por la persistencia de cierres y por un desnivel que dificulta el diálogo con el Paseo de los Curas, resuelto sólo de forma parcial con una rampa. A ello se añadió el impacto de la actividad turística: la llegada simultánea de varios cruceros multiplicó la circulación por el interior del recinto, reforzando el efecto barrera entre la operativa portuaria y los nuevos ámbitos ciudadanos. Y, a escala metropolitana, persistieron incertidumbres ferroviarias y la inercia de una gran vía paralela al mar en el sector occidental, cuya sección urbana continúa separando barrios del litoral. La integración, pese a los hitos, mantenía cuentas pendientes con la movilidad.

Con todo, la apertura de los muelles centrales supuso un salto simbólico y devolvió la cotidianidad del puerto a los malagueños, que podían ahora pasear a lo largo de los muelles, asomarse a los atraques o mirar de cerca la maniobra de barcos y la operativa de la terminal. La instalación del Centre Pompidou Málaga en los espacios reservados del muelle 1 ratificó al puerto como extensión cultural del Centro histórico, capaz de atraer visitantes y, al tiempo, de anclar rutinas locales. La dársena de megayates y las terminales de cruceros terminaron de perfilar un ecosistema urbano‑portuario mixto, donde comercio, ocio y logística conviven con una atención creciente a la gestión ambiental y a la movilidad sostenible. Esa misma convivencia obligó a afinar la gobernanza: coordinar picos de demanda, ordenar accesos, medir impactos y reinvertir plusvalías urbanas en mitigaciones logísticas y ambientales.

Not everything went as envisaged, however. On Quay 1, commercial logic diluted the impetus for the large square around La Farola and the desired continuous rooftop balcony‑promenade; on Quay 2, urban continuity was constrained by persisting fences and a level change that hampers the dialogue with Paseo de los Curas, only partially addressed by a ramp. To this was added the impact of tourist activity: the simultaneous arrival of several cruise ships multiplied circulation within the precinct, reinforcing the barrier effect between port operations and the new civic areas. At the metropolitan scale, rail uncertainties persisted, as did the inertia of a major east–west road parallel to the sea in the western sector, whose urban cross‑section continues to separate neighbourhoods from the shore. Despite the milestones, integration still had unfinished business with mobility.

Even so, opening the central quays represented a symbolic leap and restored the port’s everyday presence to the people of Málaga, who could now walk along the quays, look out over the berths, or observe up close ship manoeuvres and terminal operations. The installation of the Centre Pompidou Málaga in the reserved spaces of Quay 1 confirmed the port as a cultural extension of the historic centre, capable of attracting visitors while anchoring local routines. The megayacht marina and cruise terminals completed the outline of a mixed urban–port ecosystem, where commerce, leisure and logistics coexist with growing attention to environmental management and sustainable mobility. That same coexistence required finer‑grained governance: coordinating peak demand, organising access, measuring impacts and reinvesting urban value‑uplift into logistical and environmental mitigations.

Vista de los muelles uno y dos tras la intervención. (Fuente: Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga).

View of Piers One and Two after the intervention. (Source: Málaga Port Authority).

El tablero actual: decisiones que definen una silueta

The Current Board: Decisions that Define a Skyline

A pesar de los logros, la integración puerto‑ciudad no está cerrada. El Plan Litoral aspira a suturar las discontinuidades entre Plaza de la Marina, Parque, Palmeral y muelle 1 mediante pasos a cota, soterramientos selectivos y un corredor verde que reordene el tráfico Este‑Oeste, priorizando caminar y pedalear. Sólo así la proximidad visual se convertirá en proximidad efectiva, y el borde dejará de ser una secuencia de piezas bien resueltas pero desconectadas.

En este contexto, el muelle 4 (Heredia) emerge como bisagra entre la ciudad activa del Ensanche —el Soho— y la dársena operativa. Si bien se han planteado soluciones centradas en oficinas o hotel, la experiencia acumulada sugiere que el éxito requiere un programa mixto que combine actividad económica con equipamientos de base educativa y cultural, residencias vinculadas al conocimiento y usos de proximidad (incluida la cadena de valor pesquera). Un centro de interpretación del puerto, con miradores sobre la operativa real, contribuiría a integrar simbólicamente el trabajo portuario en el imaginario cotidiano. La clave será abordar la zona con una operación unitaria, reglas nítidas de convivencia de usos y respaldo interadministrativo.

Despite the achievements, port–city integration is not complete. The Plan Litoral aims to stitch up discontinuities between Plaza de la Marina, the Parque, the Palmeral and Muelle 1 by means of at‑grade crossings, selective tunnelling and a green corridor that reorganises east–west traffic, prioritising walking and cycling. Only then will visual proximity become effective proximity, and the edge ceases to be a sequence of well‑designed but disconnected pieces.

In this context, Quay 4 (Heredia) emerges as a hinge between the active city of the Ensanche—the Soho—and the operational basin. Although solutions focused on offices or a hotel have been mooted, accumulated experience suggests success will require a mixed programme combining economic activity with education‑ and culture‑based facilities, knowledge‑linked residences and local‑proximity uses (including the fishing value chain). An interpretation centre for the port, with viewpoints over real operations, would help embed port work symbolically in the everyday imaginary. The key will be to approach the area with a unitary operation, clear rules for use coexistence and inter‑administrative backing.

Vista aérea actual del puerto de Málaga. (Fuente: Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga).

Current aerial view of the Port of Málaga. (Source: Málaga Port Authority).

Por su parte, la plataforma de San Andrés, tradicionalmente industrial, avanza hacia un paisaje híbrido de puerto deportivo, áreas comerciales y un gran parque lineal conectado con el paseo de poniente. Diseñarla con criterios de resiliencia costera —pensando en los temporales de Levante— y de continuidad ecológica y ciclista permitiría convertirla en un umbral occidental ejemplar del sistema puerto‑ciudad. Aquí, más que en ningún otro ámbito, la coordinación entre protección costera, movilidad y programación de usos será determinante para evitar soluciones parciales que luego resulten difíciles de corregir.

La torre hotel prevista en el dique de Levante se ha convertido en el símbolo del debate sobre qué ciudad y qué puerto desea Málaga proyectar. Sus promotores ponen el acento en la tracción económica, la creación de empleo y el posicionamiento en segmentos turísticos de alto gasto; sus detractores señalan los impactos paisajísticos, el riesgo de gentrificación y los desajustes con la memoria del frente portuario histórico. Sea cual sea el desenlace, la decisión debe apoyarse en herramientas transparentes: evaluación del balance urbano neto (aportes fiscales y sociales frente a costes de accesibilidad), análisis de huella de carbono y energía a lo largo del ciclo de vida, estudio de compatibilidad de usos y simulaciones rigurosas de visibilidad e impacto en la silueta. Este ejemplo, permite evaluar que la integración puerto-ciudad no pasa sólo por la apertura de los muelles a la ciudad, sino que trasciende lo físico, para adquirir una dimensión simbólica e identitaria, que le es intrínseca y que, en casos como este, se advierte como pieza fundamental en su engranaje.

For its part, the San Andrés platform, traditionally industrial, is evolving towards a hybrid landscape of marina, commercial areas and a major linear park connected to the western promenade. Designing it with coastal‑resilience criteria—mindful of Levanter storms—and with ecological and cycling continuity would allow it to become an exemplary western threshold of the port–city system. Here, more than anywhere else, coordination among coastal protection, mobility and land‑use programming will be decisive to avoid partial solutions that later prove hard to correct.

The hotel tower proposed on the Levante breakwater has become the symbol of the debate over what city and what port Málaga wishes to project. Its promoters emphasise economic traction, job creation and positioning in high‑spend tourist segments; its detractors point to landscape impacts, the risk of gentrification and misalignments with the memory of the historic waterfront. Whatever the outcome, the decision should rest on transparent tools: assessment of net urban balance (fiscal and social contributions versus accessibility costs), whole‑life carbon and energy analysis, a use‑compatibility study, and rigorous simulations of visibility and skyline impact. This example shows that port–city integration is not only about opening quays to the city; it also transcends the physical, acquiring an intrinsic symbolic and identity dimension that, in cases like this, becomes a fundamental cog in the overall mechanism.

A modo de conclusión: claves para la integración

By Way of Conclusion: Keys to Integration

La experiencia de planificación en el caso del Puerto de Málaga, y en concreto la evolución del Avance de 1991 al Plan de 1998, o del concurso específico de 2000 al Protocolo de 2004, permite vislumbrar que la integración avanza sólo cuando existe verdadera cooperación entre instituciones, permitiendo superar bloqueos, reducir la incertidumbre y elevar la calidad de las decisiones.

A ello se debe sumar la economía híbrida del sistema. La coexistencia de contenedores, cruceros, marinas y usos ciudadanos exige medir impactos cruzados y reciclar plusvalías hacia mejoras logísticas (accesos dedicados, digitalización de operaciones, coordinación de ventanas horarias), urbanas (espacio público continuo, gestión del calor urbano) y ambientales (electrificación de atraques, control de emisiones, gestión de residuos). Sin ese retorno pactado, la convivencia se resiente y vuelven las lógicas de suma cero.

Pero tampoco debe dejarse atrás la operativa. Un sistema puerto‑ciudad integrado, como el caso de Málaga, requiere un plan de movilidad que ordene los flujos turísticos (lanzaderas de bajas emisiones, rutas peatonales claras desde terminales al Centro, gestión de puntas horarias), garantice accesos logísticos dedicados y reduzca barreras en el frente litoral. La combinación de micro‑soterramientos, pasos a cota bien diseñados, itinerarios ciclistas continuos y señalética unificada puede transformar en pocos años la experiencia de acceso sin comprometer la seguridad operativa.

A estas tres, cabe añadir un cuarto principio transversal: cuidar la dimensión simbólica. La identidad cultural del paisaje marítimo de Málaga no se resume en metros cuadrados de paseo o en la cifra de atraques; se expresa también en cómo se percibe el puerto en relación con el resto de la ciudad. Tener en cuenta esa perspectiva contribuye a legitimar la integración, reforzando el reconocimiento del ciudadano como espacio propio, y evitando el rechazo de operaciones que se perciben como ajenas.

Treinta años después de aquel PGOU que colocó al puerto en la agenda urbana, Málaga dispone de un frente marítimo que sus habitantes recorren y reconocen como propio, y de un puerto que ha ampliado su perímetro operativo mirando al mar. Entre ambos persisten fricciones —movilidad, paisajes en disputa, compatibilidades finas—, pero también una evidencia: cuando las administraciones comparten proyecto, financiación y calendario, el puerto deja de ser una frontera y el mar vuelve a ser una plaza de la ciudad.

El reto de la próxima década no es menor. Se trata de convertir los logros espaciales en continuidad urbana plena; de transformar las piezas icónicas en valor neto para el conjunto; de completar el Plan Litoral por fases con obra útil inmediata; de hacer del muelle 4 una bisagra funcional y cívica; de configurar San Andrés como umbral resiliente del sistema; y de anclar la toma de decisiones en matrices de compatibilidad que ordenen intensidades, horarios y accesos. Si Málaga persevera en ese trípode de pactos, retornos y accesibilidad, y acompasa la integración física con la simbólica, la ciudad portuaria que ya se vislumbra será, además, una ciudad más habitable, más competitiva y más consciente de su modo de habitar el Mediterráneo.

Planning experience in the case of the Port of Málaga—most notably the evolution from the 1991 Preliminary Draft to the 1998 Plan, or from the 2000 specific competition to the 2004 Protocol—suggests that integration advances only when there is genuine cooperation between institutions, allowing blockages to be overcome, uncertainty reduced and decision quality raised.

To this must be added the system’s hybrid economy. The coexistence of containers, cruises, marinas and civic uses demands measuring cross‑impacts and recycling value‑uplift into logistical improvements (dedicated access, digitalisation of operations, coordination of time slots), urban enhancements (continuous public space, urban‑heat management) and environmental gains (shore‑power electrification at berths, emissions control, waste management). Without that agreed return, coexistence suffers and zero‑sum logics resurface.

Operations must not be sidelined either. An integrated port–city system, as in Málaga, requires a mobility plan that organises tourist flows (low‑emission shuttles, clear pedestrian routes from terminals to the centre, peak‑hour management), guarantees dedicated logistics access and reduces barriers along the seafront. A combination of targeted short underpasses, well‑designed at‑grade crossings, continuous cycling routes and unified wayfinding can transform the access experience within a few years without compromising operational safety.

To these three we should add a fourth transversal principle: care for the symbolic dimension. The cultural identity of Málaga’s maritime landscape is not summed up by square metres of promenade or the number of berths; it is also expressed in how the port is perceived in relation to the rest of the city. Taking that perspective into account helps to legitimize integration, reinforcing citizens’ recognition of the area as a space of their own, and avoiding rejection of operations perceived as alien.

Thirty years after that PGOU which placed the port on the urban agenda, Málaga boasts a waterfront that its inhabitants traverse and recognise as their own, and a port that has expanded its operational perimeter seaward. Frictions remain between the two—mobility, contested landscapes, fine‑tuned compatibilities—but so does an evident lesson: when administrations share a project, funding and timetable, the port ceases to be a frontier and the sea once again becomes one of the city’s squares.

The challenge of the next decade is no small one. It is to convert spatial achievements into full urban continuity; to transform iconic pieces into net value for the whole; to complete the Plan Litoral in phases with immediately useful works; to make Quay 4 a functional and civic hinge; to shape San Andrés as a resilient threshold of the system; and to anchor decision‑making in compatibility matrices that organise intensities, schedules and access. If Málaga perseveres with that tripod of pacts, returns and accessibility—and harmonises physical integration with symbolic integration—the port city that is already coming into view will also be a city that is more liveable, more competitive and more conscious of its way of inhabiting the Mediterranean.

IMAGEN INICIAL | Vista aérea del Puerto de Málaga. (Fuente: Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga).

HEAD IMAGE | Aerial view of the Port of Málaga. (Source: Málaga Port Authority).

╝

REFERENCIAS

REFERENCES

Andrade Marqués, M.J. (2012), Mar a la vista. Las transformaciones del puerto de Málaga en el debate de los waterfronts, Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Málaga.

Andrade, M.J. & Peralta, A. (2015), “Proyectos Urbanos 1: La integración Puerto-Ciudad”, in R. Báez Muñoz & P. Jiménez Melgar (coords.), Agenda 21 Málaga 2015. Agenda urbana en la estrategia de sostenibilidad integrada 2020—2050, pp. 167-172, Servicio de Proyectos Europeos, Observatorio de Medio Ambiente Urbano, Ayuntamiento de Málaga, Málaga.

Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga (1991), Avance del Plan Especial del Puerto, Málaga.

Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga (1998), Plan Especial del Puerto, Málaga.

Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga (2010), Plan Especial del Sistema General del Puerto de Málaga. Texto Refundido, Málaga.

Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga (2023), Plan Estratégico de la Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga 2024-2030, Málaga.

Ayuntamiento de Málaga (1983), Plan General de Ordenación Urbana, Málaga.

Ayuntamiento de Málaga (2011), Plan General de Ordenación Urbana, Málaga.

Cabrera Pablos, F. (2025), De un Puerto, una Ciudad: ingenieros y militares, arquitectos y marinos en las obras malagueñas, Autoridad Portuaria de Málaga, Málaga.

Caffatena J.A. (2013), “Un puerto que extiende el centro de la ciudad. PORTUS: the online magazine of RETE, no. 25, https://portusonline.org/un-puerto-que-extiende-el-centro-de-la-ciudad/

Costa, A., de la Torre, C. & Peralta, A. (2005), “El Plan Especial del Puerto de Málaga. Breve Historia de un Largo Proceso”, in Interreg III B. Cooperación de metrópolis mediterráneas. Proyecto piloto integración de puerto y ciudad, Ayuntamiento de Málaga, Málaga.

Ettorre, B. & Andrade-Marquez, M.J. (2024), “Coexistencia puerto-ciudad. El estudio del impacto medioambiental de los cruceros en Málaga como base de una integración sostenible”, in S. Olivero Guidobono (coord.), Materiales, técnicas, estrategias y resultados. Planteamientos humanos ante los retos socio-culturales, pp. 1061-1083, Dykinson.

Falabella, I. (2015), Malaga waterfront: the new door, Master Thesis. Politecnico di Milano, https://hdl.handle.net/10589/108624/

Fernández Salinas, V. & Silva Pérez, R. (2018), “Aportación al debate: sobre los valores patrimoniales de los espacios portuarios: aplicación al puerto de Málaga”, in F. Cebrián Abellán (coord.), Ciudades medias y áreas metropolitanas: de la dispersión a la regeneración, pp. 583-602, Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La-Mancha, Ciudad Real.

García Bujalance, S. (2016), El Plan General de Málaga de 1983. Un instrumento para la transformación urbana, Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Málaga, http://hdl.handle.net/10630/13750/

Grindalay Moreno, A.L. & García Vidal, A. (2022), “Una paradigmática ciudad portuaria”, Revista de Obras Públicas, no. 3639, pp. 106-113. https://www.revistadeobraspublicas.com/articulos/una-paradigmatica-ciudad-portuaria/

Machuca Santa-Cruz, L. (1997), Málaga, Ciudad Abierta. Origen, cambio y permanencia de una estructura urbana, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Málaga, Málaga.

Moyano Retamero, J. (2022), “Málaga, un puerto abierto a su ciudad”, Revista de Obras Públicas, no. 3639, pp. 158-65. https://www.revistadeobraspublicas.com/experiencias/malaga-un-puerto-abierto-a-su-ciudad/

Navas Carrillo, D. (2024), “The Transformation of the Malaga Port: New Challenges for Port-City Integration”,PORTUS: the online magazine of RETE, no. 48, https://portusonline.org/the-transformation-of-the-malaga-port-new-challenges-for-port-city-integration/

Puertos del Estado (2025). “Puertos que hacen ciudad. Proyectos estratégicos que unen competitividad portuaria y regeneración urbana”, Tramos, Revista del Ministerio de Transportes y Movilidad Sostenible, no. 760, pp. 117-124. https://www.transportes.gob.es/recursos_mfom/comodin/recursos/17_puertos_que_hacen_ciudad.pdf/

Reinoso Bellido, R. (2005), Topografías del paraíso. La construcción de la ciudad de Málaga entre 1897 y 1959, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Málaga, Colegio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos de Málaga, Málaga.