Livorno is a port city and it is in the district known as Venezia Nuova that the historic mercantile and maritime fabric of the city can still be observed and where the canal network linking sea and land is a distinctive component of the form of the city. A structured network on the urban stretch of the Navicelli Canal, on the Fosso Reale and on the Fosso della Venezia, but also comprising the stores, cellars and warehouses that overlook it. This constitutes an urban system that can be said to be one of kind and which was capable of rising from the huge destruction of the bombardment of Livorno.

To get to the Venezia Nuova district, which takes its name from the workforce and techniques imported from Venice, it is necessary to delve into the history of Livorno with its tax relief, commercial activities and the construction of port works and fortifications.

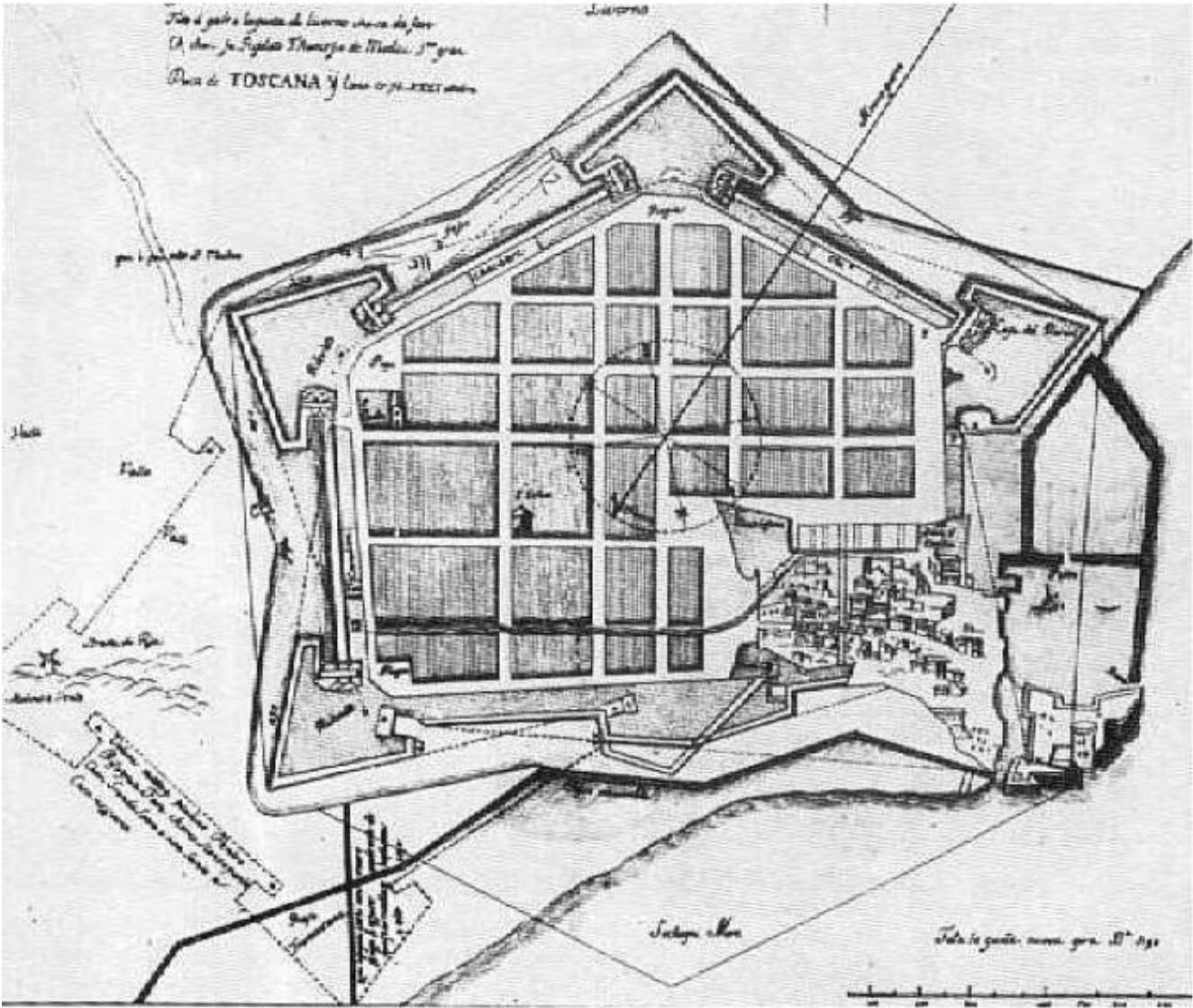

In the sixteenth century, Buontalenti designed an organised, pentagonal, walled settlement, protected by bulwarks and moats (image below). The inhabited area expanded between the end of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the eighteenth century into areas obtained from the partial destruction of the Fortress.

The major construction works of the time were concentrated in the Venezia Nuova area. The olive oil store, Bottini dell’Olio (now home to the City Museum), the merchant houses on Via Borra, the Baroque churches of San Ferdinando and Santa Caterina with the Dominican convent, the Case Pie, the fish market, Pescheria Nuova, and the Jesuit Convent were also built. The Fossi canal system became an urban trading artery. The fillings and the advance of the city over the canals necessitated a system of paved slopes and steps which mean that Livorno should also be observed in three-dimensions. Civil construction descended from the road to the canals and cellars and warehouses were built to connect them to shops and homes so that goods could be transported and loaded from the water.

From the mid-sixteenth century, Buontalenti planned and worked on the fortified city with pentagonal perimeter delimited by a moat.

In the twentieth century, modern public and private urban life made its way into the old quarter and again the construction of the city conversed with the water network (image below). Squares, palaces, the Benci Schools, the Dutch German Church, the grandiose Mercato delle Vettovaglie overlook the canals (following image). Two docks and a customs barrier were built to serve the free port and the Fosso Reale was rectified. As long as the maritime and mercantile economic model lasted, the city consolidated the morphology of water, brick and stone with the expansion of cellars and buildings in depth, width and height.

When, in the second half of the nineteenth century, the functioning of the port changed with the loss of customs exemptions and, in the twentieth century, new logistics for goods arrived, the canal system lost its original function and so the cellars and warehouses were gradually destined for other purposes related to sport, boating, fishing, music, food and wine and art.

The twentieth century was also that of rebirth and post-war restoration, of the reopening of the Navicelli Canal, which had been covered for the sake of hygiene at the end of the twentieth century, of events and of the discovery of squares, palaces, churches and bridges along the city’s canals.

Piazza della Repubblica, built on the plans by the architect Luigi Bettarini in the first half of the 19th century.

The Livorno canal network is a complex infrastructure that must be included in the urban renewal project, primarily undergoing reclamation and restoration, and seen as strategic at a time when programs and projects for the city and the port are outlined.

In municipal administration planning, the development of the city on water of Livorno is not a sector or residual objective, but rather a strategic and transversal objective for sectors and departments.

This includes the safeguarding of Livorno’s maritime identity; the enhancement of areas and buildings linked to the water cycle; the management of the navigability of the Fossi Medicei, creating a sustainable mode of transport with benefit to tourism; the maintenance of social boating as a value; the protection and enhancement of the cellars, fortresses, ramparts and city architecture linked to the water, in an overall economic boost through tourism, trade and culture. This includes the renewing the Harbour Station, the Fortezza Vecchia and Forte San Pietro, the projects for the technological centre and the cleaning and reclamation of the canals, which had already begun as the harrowing pandemic took hold.

The Central Market of Livorno with a view of Fosso Reale.

The canals are also part of the project for the Third Millennium, confirming the events in the history of Livorno’s urban development, in which the district, district of Venezia Nuova features at the heart. Citizen participation activities and consultation with competent bodies, including research centres, will be set up in order to establish the ways and means for the renovation of the canals. Funding will be sourced via the EU 2021-2027 cohesion policy based on the 5 objectives (Smarter Europe, Greener Europe, a more Connected Europe, a more Social Europe, a Europe closer to citizens), where axes are identified strategies wherein culture is a vehicle for economic and social cohesion.

The view of the canals as a cultural asset, an environmental device, a means of sustainable transport and a factor for promoting tourism and commercial development requires that the development of projects cannot be limited to the water network alone but must also include the restoration of stairways, cellars and warehouses, so that the system point to point regains structured social and economic significance. In this way, the regeneration of urban spaces at street level in the district of Venezia Nuova can also be managed to take into account the physical, social and economic aspects, restoring the inseparable vitality of the canals, buildings, steps and squares. Accessibility, aesthetic quality and new forms of enterprise, such as high quality historical-artistic incubators, conservation-friendly, tech-innovation economies, venues for consuming food and wine, local products and socialising will all contribute to a real and perceived sense of certainty.

Head image: The urban plan of the Pentagon of Livorno by Bernardo Buontalenti.

I Fossi di Livorno al centro della storia, della forma e del progetto di città

Livorno è città portuale, e della struttura mercantile e marittima storica permane testimonianza nel quartiere della Venezia Nuova, ove la rete d’acqua che ha connesso mare e terra mantiene un rango centrale nella forma della città. Rete strutturata sul tratto urbano del Canale dei Navicelli, sul Fosso Reale e sul Fosso della Venezia, ma costituita anche dai fondi, dalle cantine e dai magazzini che vi si affacciano, essa costituisce un sistema urbano che può dirsi unico nel suo genere, riuscito a riemergere dopo gli ingenti bombardamenti bellici che hanno distrutto Livorno.

Per arrivare al quartiere della Venezia Nuova, che prende il nome dalla manodopera e dalle tecniche importate dal capoluogo veneto, bisogna inoltrarsi nella storia di Livorno fra sgravi fiscali, attività commerciali e costruzione di opere portuali e di fortificazioni.

Nel Cinquecento il Buontalenti progetta un abitato ordinato e cinto di mura secondo una forma pentagonale, protetto da baluardi e fossati (immagine seguente). L’abitato si espanderà tra la fine del Seicento e l’inizio del Settecento in aree ricavate dalla parziale distruzione della Fortezza.

Nella Venezia Nuova si concentrarono le principali attività edilizie dell’epoca. Vengono realizzati i Bottini dell’Olio (oggi sede del Museo della città), i palazzi mercantili sulla via Borra, le chiese barocche di San Ferdinando e Santa Caterina con il convento domenicano, le Case Pie, la Pescheria Nuova e il Convento gesuita. Il sistema dei Fossi diventa arteria commerciale urbana. I riempimenti e l’avanzare della città sui fossi determinano quel sistema di discese e di scalinate lastricate che rende Livorno una città da guardare sempre in chiave tridimensionale. L’edificazione privata scende dalla strada ai fossi e si realizzano le cantine e i magazzini che li collegano alle botteghe e alle abitazioni per il trasporto delle merci e il loro scambio dall’acqua alla terra ferma.

Dalla metà del Cinquecento Buontalenti progetta e lavora alla città fortificata in un perimetro pentagonale delimitato da un fossato.

Nel XX Secolo si fa largo l’urbanità moderna pubblica e privata nel quartiere antico e di nuovo la costruzione della città dialoga con la rete d’acqua (immagine seguente). Piazze, palazzi, le Scuole Benci, il Tempio degli Olandesi, il grandioso Mercato delle Vettovaglie si affacciano sui fossi (immagine successiva). Vengono realizzate due darsene e una cinta doganale a servizio del porto franco, viene rettificato il Fosso Reale. Finché dura il modello economico marittimo e mercantile la città consolida la morfologia d’acqua, di mattoni e di pietra con l’ampliarsi delle cantine e dei palazzi in profondità, larghezza e altezza.

Quando nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento cambia il funzionamento del porto con la perdita delle franchigie doganali e nel Novecento arriva la logistica nuova per le merci, il sistema dei fossi perde la sua funzione originaria e così accade per le cantine e i magazzini progressivamente destinati ad attività varie e diverse legate allo sport, alla nautica, alla pesca, alla musica, all’enogastronomia, all’arte.

Il Novecento è anche il secolo della rinascita e dei restauri post bellici, della riapertura del Canale dei Navicelli tombato in nome dell’igiene e della salute già a fine Secolo XX, degli eventi, della scoperta di piazze, palazzi, chiese, ponti a cui accostarsi navigando in battello nei fossi cittadini.

Piazza della Repubblica, realizzata su progetto dell’architetto Luigi Bettarini nella prima metà del XIX secolo.

La rete dei canali livornesi è da considerare una infrastruttura complessa da coinvolgere necessariamente nel progetto di rinnovo urbano, in primo luogo da assoggettare a bonifica e restauri e da considerare luogo strategico in un momento nel quale si delineano programmi e progetti per la città e il porto.

Nella programmazione dell’Amministrazione comunale lo sviluppo di Livorno città d’acqua non è obiettivo settoriale né residuale, ma anzi strategico e trasversale a settori e assessorati.

Vi sono incluse la salvaguardia dell’identità marittima; la valorizzazione degli spazi e degli edifici legati al ciclo delle acque; la gestione del sistema dei Fossi Medicei per la navigabilità creando una modalità di trasporto sostenibile anche con utilità e valenza turistica; il mantenimento della nautica sociale come presenza valoriale; la tutela e la valorizzazione di cantine, fortezze, bastioni e architetture cittadine legate all’acqua, in una spinta economica complessiva attraverso il turismo, il commercio, la cultura. Ne fanno parte i nuovi assetti della Stazione Marittima, della Fortezza Vecchia e di Forte San Pietro, i progetti per il polo tecnologico e le opere di pulizia e di bonifica dei canali, già iniziate nel tormentato periodo della pandemia.

Il Mercato Centrale di Livorno con prospetto su Fosso Reale.

I fossi si trovano coinvolti nel progetto di Livorno anche nel Terzo Millennio, a conferma di quanto raccontano le vicende della costruzione del suo profilo urbano e in esse la storia del quartiere della Venezia Nuova, cuore del cuore della città. Per la loro riqualificazione saranno attivati percorsi di partecipazione cittadina e saranno costituiti appositi tavoli fra i soggetti competenti, inclusi i centri di ricerca. Le risorse saranno cercate nel plafond europeo, considerata la politica di coesione 2021-2027 che si sviluppa su 5 obiettivi di policy (un’Europa più intelligente, più verde, più connessa, più sociale, più vicina ai cittadini), ove si individuano assi strategici costituiti dalla cultura come veicolo di coesione economica e sociale.

La visione dei fossi come bene culturale, dispositivo ambientale, mezzo di trasporto sostenibile e fattore di promozione dello sviluppo turistico e commerciale comporta la declinazione di progetti che non possono limitarsi alla rete d’acqua ma devono comprendere il restauro degli scalandroni, delle cantine e dei magazzini, così che il sistema degli scali riassuma un rango sociale ed economico strutturato. In questo modo anche la rigenerazione degli spazi urbani a livello stradale nel quartiere della Venezia Nuova potrà essere trattata in modalità intersettoriale – fisica, sociale, economica – recuperando la vitalità inseparabile dei canali e dei palazzi, delle discese e delle piazze. Ne avranno beneficio anche la sicurezza reale e quella percepita che derivano dall’accessibilità, dalla qualità estetica, dall’introduzione di attività varie e diverse, come incubatori di alta qualità storico-artistica, economie innovative rese compatibili con la tutela grazie alla tecnologia, offerte sempre attrattive di consumo enogastronomico, di prodotti locali e di socialità.

Head image: Il progetto urbanistico del Pentagono di Livorno di Bernardo Buontalenti.