Montevideo is located on the River Plate, the river mouth of the 3440 km long Paraná Paraguay Waterway. The River Plate is the gate to the heart of Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay and the richest provinces of Argentina. This strategic location of the port of Montevideo is the main reason of the existence of Uruguay as an independent country, according to former President Lacalle Herrera of Uruguay. The territory was an area of dispute, first between Spain and Portugal, and later between Argentina and Brazil. The port was conceived by Spain as a logistic centre for the region. The local commerce was initially meaningless. In 1928, British diplomacy suggested a political solution to the conflict area by creating a new country named Uruguay. Access to the rest of South America remains a key activity today. Imports and exports to and from Uruguay represent still today less than 50% of the port activity.

Port, city and country grew up together since Montevideo’s foundation in 1724. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century Uruguay experienced a huge immigration wave. Uruguay had the highest rate of immigrants per inhabitant of the Americas (8.5 immigrants per inhabitant). The port was the arrival gate for the “new Uruguayans”. In the 1930s and 40s, new immigration waves entered the country through Montevideo port. Several generations of citizens have had personal experiences with the port and are proud of it. A visit to see the port operations at the berth was one of the preferred leisure activities of the Montevideans still in the 1980s.

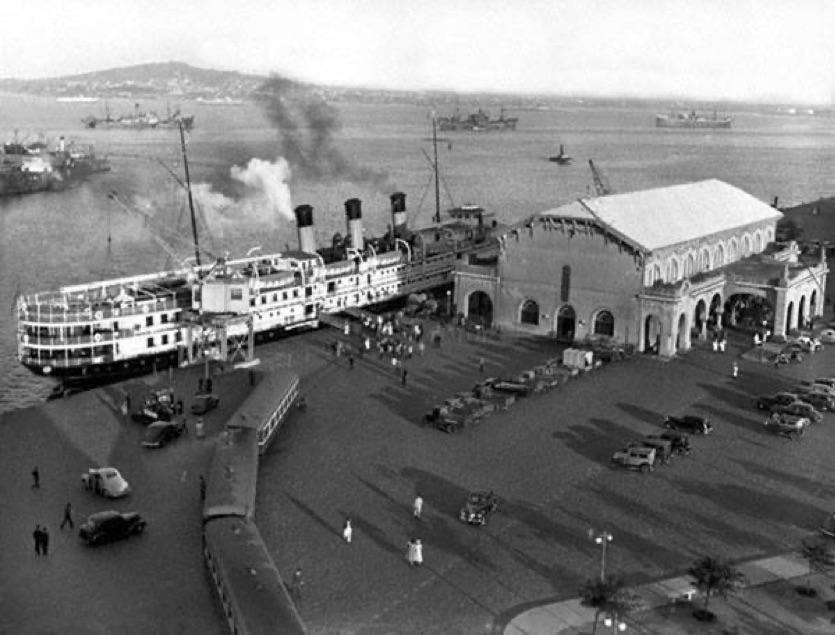

The ancient port of Montevideo.

This access to the port has become part of port city culture in Montevideo. According to Kroeber and Kluckhohn (1952), port city culture is related to numerous different cultures that clash in port cities, under impacts of internal and external political, economic and social forces for beneficial of port and trade activities. According to Hein (2020), port city culture is based on a strong and dedicated collaboration among diverse groups of public and private actors from different backgrounds around shared values. Kroeber and Kluckhohn definition is applicable to Montevideo before the 1990s. Port city culture in Montevideo implied also the physical presence of citizens at the port berths to observe operations. Since early 2000s, access to the port and the Uruguayan way of port culture has disappeared. Hein’s concept applies perfectly to Montevideo’s Port Community represented by active port stakeholders.

The worldwide implementation of the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS code – a consequence of the attacks of 9/11), the application of the port landlord philosophy since the 1990s and the adaption of high-level technologies impede wide port access for citizens. As different cargo types co-exist in the port (bulk cargo, break bulk cargo, project cargo, Ro-Ro, container operations and the Pax ferry terminals), the rules for cargo transport and the limit imposed on access apply to the port as a whole. Different to the older generations, young Montevideans can access only the Pax terminal to travel to Buenos Aires on the world fastest ferry named Francisco – after the pope. Before, berth access was practically unrestricted.

In 2005, the port authority launched an ambitious port infrastructure plan, which affected urban areas through traffic increase and port expansion to still unused urban areas. Territorial and bay waterfront issues became a topic of debate between the port authority and the Montevideo government.

The establishment of a coordination commission between port and city authorities in 2005 initiated a process to recover the citizens’ port culture and to find amicable urban solutions for the areas of interaction between port and city without disturbing port growth and operations. Port authorities and city administration designed safe port bay balconies accessible to everybody to watch port operations. After 10 years of tensions between the port authority and the local government, positive results of intensive negotiations were emerging, when the COVID-19 pandemic started.

The COVID-19 outbreak implies a new challenge for the port authorities. The Pax terminal needs to be moved out of the port in order to increase port operation safety and to guarantee increased social distancing in new facilities. The technological changes may boost productivity significantly but will negatively impact on employment. Worker unions need to accept that port operations will drastically reduce employment where possible to minimize human contact. The port accessibility will be even more stringent and finally disappear once the ferry Pax terminal is relocated outside of the port. This will also have impact on cruise activities.

Montevideo port has been a successful cruise terminal for many years now. Every year, approximately 80 cruise vessels dock in the port during the (southern hemisphere) summer between November and March in public berths. During the COVID-19 outbreak, Montevideo port accepted cruise vessels with infected passengers and crew members, which were not allowed to call on other regional ports, under a strict and successful medical protocol. This action allowed thousands of cruise passengers to return back to their countries healthy. The most famous case was the Australian cruise vessel Greg Mortimer, which had a large number of passengers and crew members infected with COVID-19.

Such engagement is possible only on the short term. Even stronger sanitary measures will surely be implemented in Uruguay in the future. The port may not accept such a large number of cruise vessel to call Montevideo anymore. The new ferry terminal may not be able to receive cruise vessels due to draught restrictions. The port is likely to restrict the number of berths available for cruise vessels. This will impact negatively on tourism business and consequently on employment.

The long-term efforts to bring port and city government together to find shared solutions, to resolve territorial issues between port growth and city development, to prevent effects of climate change and to recover port culture, have been eclipsed by the COVID-19 outbreak. It is necessary to rethink the agenda and consider the vulnerability before other possible unexpected or disruptive events.

Acknowledgement

This text has been written in the context of the Webinar organized by RETE and PortCityFutures on May 18th 2020.

It first appeared on the Leiden-Delft-Erasmus PortCityFutures Blog (https://www.portcityfutures.nl/news/challenges-for-city-development-and-port-activities-after-covid-19-the-case-of-montevideo; 20 July 2020). Special thanks for comments and reviews to Carola Hein.

References

Kroeber, A.L. and Kluckhohn, C., “Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions,” Papers. Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Harvard University (1952).

Hein, C., “The Shifting Values of Port Cities: Towards What-If Histories and Design Fiction”, 2020.

Head image: View of the Montevideo bay and hill.