╔

Una Escuela de Arquitectura portuaria

De entre las 34 Escuelas de Arquitectura de España, la de Sevilla tiene una singularidad geográfica: se sitúa a menos de 150 metros de los terrenos del Puerto que en épocas pasadas fue el centro de la actividad económica de ciudad hispalense. El desarrollo urbanístico vinculado a la Exposición Iberoamericana de 1929, de la que el solar de la Escuela de Arquitectura es heredero, no se puede entender sin la cercana ampliación del Puerto, de principios de siglo XX, derivada de la construcción del Canal de Alfonso XII y del muelle de Tablada.

Esta cercanía es el motivo por el que, entre los temas de trabajo de las asignaturas de Proyectos Arquitectónicos, es históricamente fácil encontrar los que se ubican en los terrenos del Puerto de Sevilla, tanto en solares o equipamientos accesibles a la ciudad como en las áreas restringidas a la actividad portuaria.

A ello ha podido contribuir la singularidad de la iconografía histórica de la ciudad de Sevilla, tan influyente en la conformación del inconsciente colectivo de la ciudad, en la que el protagonismo del Puerto en las composiciones de los grabados y las pinturas más difundidas, o el propio punto de vista elegido para representar la ciudad, hablan de unas márgenes fluviales llenas de actividad, no solo propiamente portuaria, sino pública y urbana en el más extenso sentido de estas palabras.

Repasando los planteamientos de proyectos académicos que se han ocupado de los terrenos del Puerto de Sevilla, bien sea en los solares accesibles o en los restringidos, podemos localizar tanto propuestas residenciales (vivienda convencional o vivienda colaborativa) como equipamientos de nueva planta, éstos últimos vinculados a la previsible transformación de la zona del muelle de Tablada en el nuevo distrito portuario de la ciudad, con sus posibles variantes de uso docente, administrativo, cultural, deportivo, comercial, e incluso en forma de parques, enlazándose en este caso con el cercano y recientemente terminado Parque del Guadaira, en el lecho del antiguo afluente del Guadalquivir.

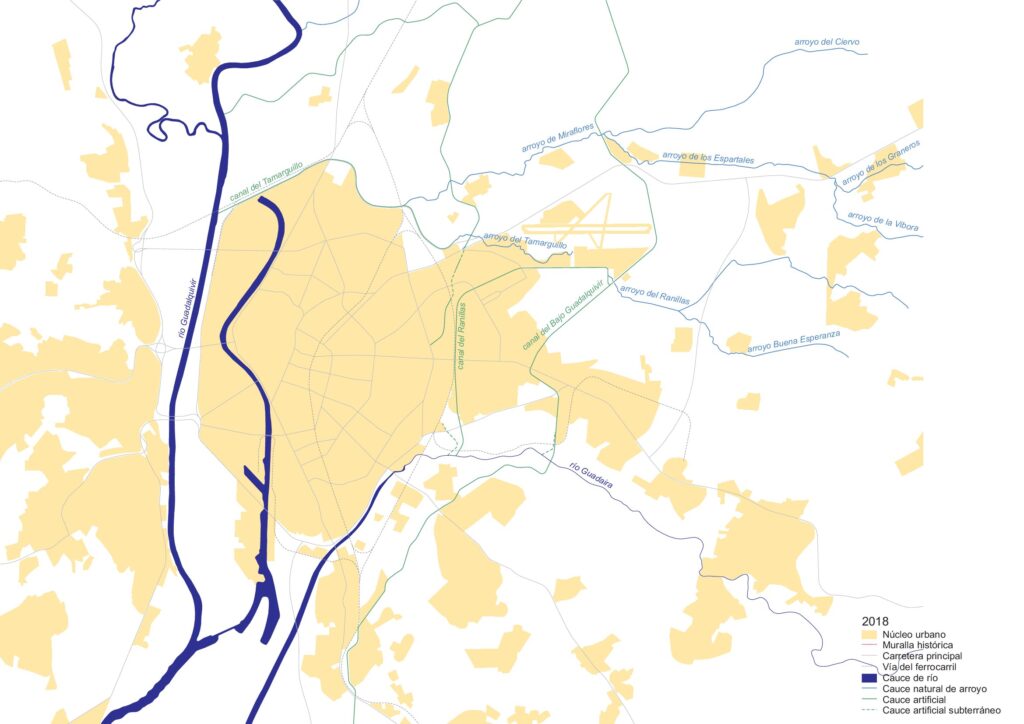

Esta tradición docente, la de ubicar las propuestas de los estudiantes de la Escuela de Arquitectura en los bordes fluviales de la ciudad, ha llevado también a rastrear y poner en valor la específica morfología hídrica que subyace en el núcleo urbano de Sevilla, históricamente atravesado por diferentes afluentes del Guadalquivir y condicionado por los esfuerzos por controlar, desviar u ocultar estos lechos fluviales, causantes, como el propio rio en su cauce original, de numerosas y dañinas riadas. Con el tiempo, los afluentes del Guadalquivir en zona urbana han desaparecido de la conciencia de la ciudad, que no de su realidad geológica, dado que de alguna manera persisten, bien sea entubados, desviados, o aliviados por canales, estos últimos los nuevos ríos artificiales utilitarios que aún discurren inadvertidamente por algunos barrios periféricos.

La actividad proyectual de la Escuela de Sevilla ha encontrado también inspiración en el tratamiento de estos cauces secundarios, bien históricos (como caso del tramo aún activo del río Guadaira o su porción transmutada en parque lineal) bien advenedizos, como el canal Ranillas, construido en la postguerra civil para controlar las avenidas del Tarmarguillo. En los últimos años el canal Ranillas ha tenido cierto protagonismo en los cursos de Proyectos Arquitectónicos, al ponerse en valor la posibilidad de rehabilitarlo como una lámina de agua recreativa al servicio del área de Sevilla Este. Para ello se sacaría partido de conexión con el Canal del Bajo Guadalquivir, el cual puede alimentarlo en determinadas épocas del año, cuando decrece la demanda de los regantes de la cuenca y se dispone de suficiente cantidad de agua para colmatar su cauce y dar vida a sus márgenes.

Of the 34 Schools of Architecture in Spain, the Seville School of Architecture has a unique geographical feature: it is located less than 150 meters from the Port, which in the past was the center of economic activity in the city of Seville. The urban development linked to the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929, of which the site of the School of Architecture is heir, cannot be understood without the nearby expansion of the Port, at the beginning of the 20th century, derived from the construction of the Alfonso XII Canal and the Tablada wharf.

This proximity is the reason why, among the topics of the Architectural Design courses, it is historically easy to find those located on the grounds of the Port of Seville, in plots or facilities both accessible to the city or restricted to public.

The singularity of the historical iconography of the city of Seville, so influential in shaping the collective unconscious of the city, may have contributed to this, in which the prominence of the Port in the compositions of the most widespread engravings and paintings, or the very point of view chosen to represent the city, speak of riverbanks full of activity, not only port activity, but public and urban ones in the broadest sense of these words.

Reviewing the approaches of academic projects that have dealt with the land of the Port of Seville, either in the accessible or restricted plots, we can locate both residential proposals (conventional housing or collaborative housing) and new facilities. The latter are linked to the foreseeable transformation of the Tablada dock area into the city’s new Port District, with its possible variants of educational, administrative, cultural, sports, commercial and even park-like uses, linking in this case with the nearby and recently completed Guadaira Park, on the bed of the former tributary of the Guadalquivir.

This teaching tradition, that of locating the proposals of the students of the School of Architecture in the fluvial edges of the city, has also led to trace and value the specific water morphology that underlies the urban core of Seville, historically crossed by different tributaries of the Guadalquivir and conditioned by the efforts to control, divert or hide these river beds, causing, like the river itself in its original course, numerous and damaging floods. Over time, the tributaries of the Guadalquivir in urban areas have disappeared from the city’s consciousness, but not from its geological reality, since in some way they persist, either piped, diverted or relieved by canals, the latter being the new artificial utility rivers that still run unnoticed through some peripheral neighborhoods.

The design activity of the School of Seville has also found inspiration in the treatment of these secondary waterways, whether historical (as in the case of the still active section of the Guadaira River or its portion transmuted into a linear park) or upstart, such as the Ranillas canal, built in the post-Civil War period to control the floods of the Tarmarguillo. In recent years, the Ranillas canal has had a certain prominence in the courses of Architectural Projects, as the possibility of rehabilitating it as a recreational sheet of water at the service of the East Seville area has been highlighted. This would take advantage of the connection with the Lower Guadalquivir Canal, which can feed it at certain times of the year, when the demand of the irrigators of the basin decreases and there is enough water available to fill its bed and give life to its banks.

El sistema fluvial de Sevilla en la actualidad. Desvíos de los afluentes naturales y nuevos canales. (© Francisco Marín Andreu, 2014).

The Seville river system at present. Diversions of natural tributaries and new canals. (© Francisco Marín Andreu, 2014).

La arquitectura junto al río, la arquitectura del Puerto…, sintagmas de una indudable apetencia para los estudiantes y los docentes, que pueden traer a la memoria alguna ilustración clásica del “sueño del arquitecto”, como la de Thomas Cole, que, tal vez no por casualidad, localiza esa ensoñación en las riberas de un puerto fluvial.

The architecture by the river, the architecture of the Port…, syntagms of an unquestionable appeal for students and teachers, which may bring to mind some classic illustration of the “architect’s dream”, such as that of Thomas Cole, who, perhaps not by chance, locates this reverie on the banks of a river port.

El sueño de los arquitectos. Thomas Cole, 1840. Museo de Arte de Toledo, Toledo, Ohio. (http://emuseum.toledomuseum.org/objects/54973/the-architects-dream/).

The Architect’s dream. Thomas Cole, 1840. Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio. (http://emuseum.toledomuseum.org/objects/54973/the-architects-dream/).

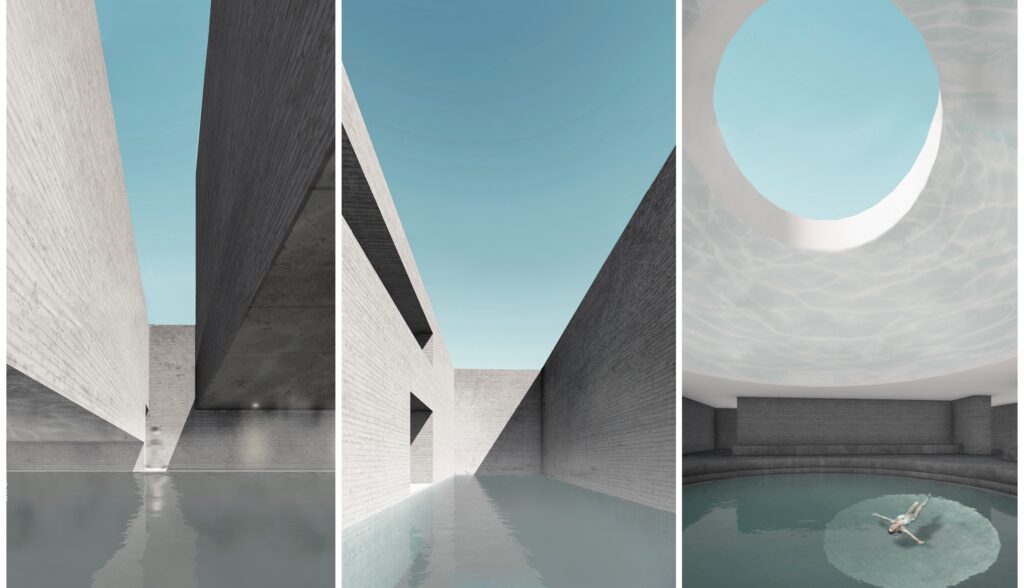

La ventaja de operar desde la academia en algún cauce fluvial supletorio, ya sin utilidad ni relevancia histórica, como es el caso del canal Ranillas, ofreció la oportunidad de explorar, sin las cortapisas del realismo de las normas portuarias o las limitaciones de propiedad, nuevas modalidades de arquitectura pública vinculada a una lámina de agua compartida por los ciudadanos y a la naturaleza que le da soporte, así como practicar un nuevo tipo de paisajismo urbano, en el ámbito de esas obras de ingeniería que cumplieron su función pero que ahora deben someterse a los nuevos paradigmas medioambientales.

The advantage of operating from the academy in a supplementary waterway, no longer useful or historically relevant, as is the case of the Ranillas canal, offered the opportunity to explore, without the constraints of the realism of port regulations or property limitations, new forms of public architecture linked to a sheet of water shared by citizens and to the nature that supports it, as well as to practice a new type of urban landscaping, within the territory of these engineering works that fulfilled their function but must now submit to new environmental paradigms.

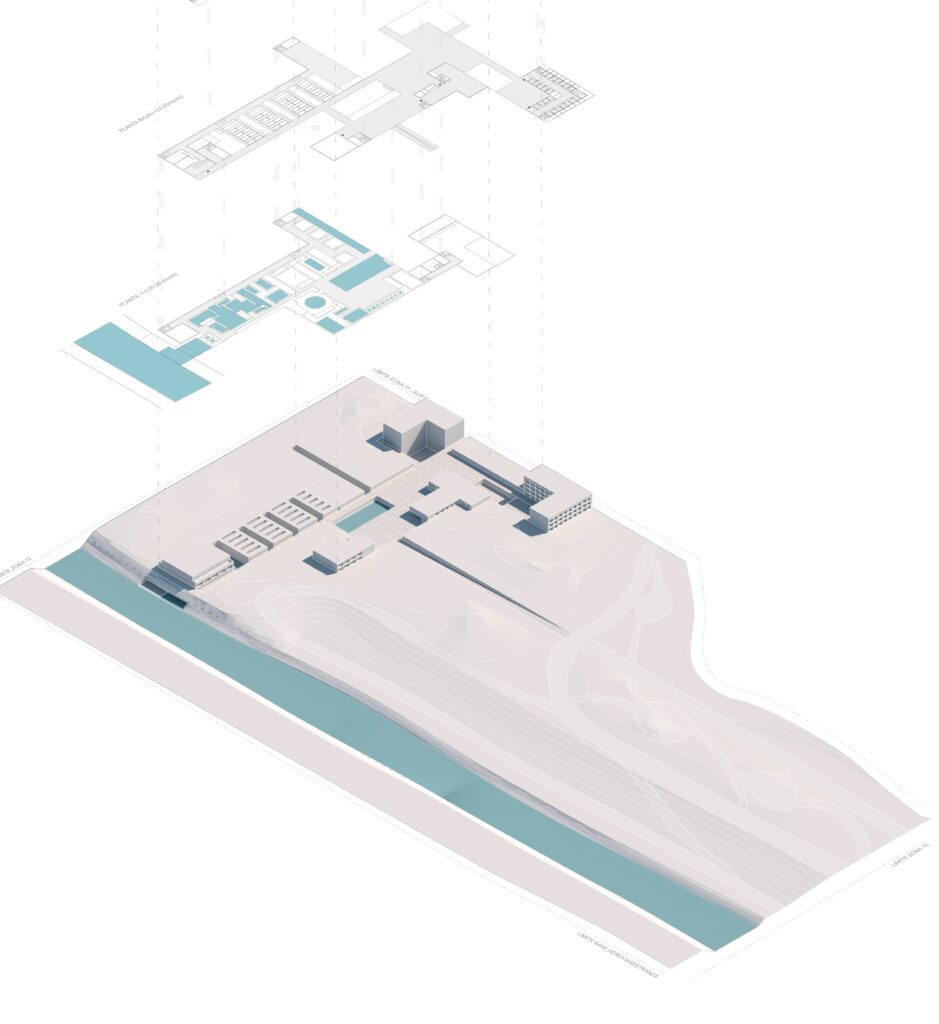

Hotel y centro acuático termal en la ribera del Canal Ranillas (Sevilla). Proyectos 9, E.T.S. de Arquitectura de Sevilla. (© Daniel Tobalo Casablanca, 2020).

Hotel and thermal aquatic center on the banks of the Ranillas Canal (Seville). Architectural Designs 9, E.T.S. de Arquitectura de Sevilla. (© Daniel Tobalo Casablanca, 2020).

Terminal de Cruceros en el Muelle de Tablada. Proyecto Fin de Carrera, E.T.S. de Arquitectura de Sevilla. (© Isidro Quintanilla Yáñez, 2024).

Cruise Terminal at Tablada Pier. Final Project, E.T.S. de Arquitectura de Sevilla. (© Isidro Quintanilla Yáñez, 2024).

Renaturalizar las ciudades

Renaturalizing cities

Trabajar en los bordes fluviales de Sevilla con los estudiantes nos hizo profundizar en las nuevas corrientes conceptuales que inspiran a lo que se ha venido en denominar Urbanismo Paisajístico, una disciplina de reciente cuño, que entiende el paisaje como el contexto en el que se debe mover la arquitectura y la ingeniería civil, y desarrolla la interacción entre los sistemas artificiales y naturales, diluyendo la frontera entre el paisaje y la ciudad, la cual se concebiría como un paisaje más, y se analizaría, trataría y proyectaría como tal [1].

Las bases teóricas de este enfoque han quedado sintetizadas, en los últimos cursos en los que la ETSA Sevilla ha estado trabajando en los bordes fluviales de su ciudad, en la siguiente batería de conceptos, englobados dentro de la idea fuerza común que hemos denominado “Renaturalizar las ciudades“.

Working on the river edges of Seville with students made us delve into the new conceptual currents that inspire what has come to be called Landscape Urbanism, a recent discipline, which understands the landscape as the context in which architecture and civil engineering should move, and develops the interaction between artificial and natural systems, diluting the boundary between landscape and city, which would be conceived as a landscape, and would be analyzed, treated and projected as such [1].

The theoretical bases of this approach have been synthesized, in recent courses in which the ETSA Seville has been working on the river edges of the city, in the following battery of concepts, encompassed within the common force idea of “Renaturalizing citie”.

- Diseñar con la naturaleza. Las ciudades modernas, y los puertos en particular, depositan sus construcciones y sus infraestructuras sobre el sustrato natural preexistente, generando una especie de máscara de hormigón, bajo la cual, no obstante, ese sustrato sobrevive, con su topografía latente, su geología y su hidrología. Las transformaciones futuras no tienen por qué basarse necesariamente en añadidos de nuevas capas o nuevas máscaras, y pueden, como una de las primeras opciones, sacar de alguna manera de nuevo a la luz la naturaleza subyacente.

- El plano horizontal permeable. La forma convencional de urbanizar se sustenta en la generación de superficies impermeables, rígidas y planas, pensadas principalmente para la facilidad de la movilidad rodada, las cuales seccionan el intercambio higrotérmico con el subsuelo. La visión paisajística del urbanismo prima por el contrario la minimización de estas cubriciones impermeables y propone su posible conversión en nuevas pieles transpirables, cuando no abiertas al sustrato natural.

- Elogio de la lentitud y de la topografía. La rapidez en las comunicaciones da sentido a la movilidad rodada pero no necesariamente a las itinerarios peatonales, que pueden dotarse de otros atractivos en su diseño: recuperar la topografía natural y las formas vernáculas de recorrerla puede enriquecer la experiencia del espacio urbano para el peatón, sobre todo si, además, en la organización de la ciudad priman ideas como la de la del “urbanismos de los cinco minutos”, que aspira a concentrar el máximo de los servicios cotidianos dentro de una asequible proximidad peatonal.

- Las raíces de lo construido. La atención al paisaje preexistente se dirige también a las alteraciones que las construcciones provocan en el sustrato natural y a considerar también como objeto del proyecto arquitectónico el diseño sostenible de estas modificaciones, para que el resultado no dañe de forma irreversible la integridad de los sistemas naturales que dan soporte a la arquitectura.

- Las arquitecturas de contacto ligero. Una forma de relacionarse respetuosamente con el sustrato natural es promover arquitecturas que se depositen de la forma más delicada posible sobre éste, con pocos apoyos, con plantas bajas sin edificar, o con tecnologías ligeras, de forma que los edificios puedan entenderse más como instalaciones reversibles y de mínima huella en el paisaje que como intrusiones pesadas y permanentes de éste.

- En contra del lugar “aclarado”. Las actitudes que ponen en el centro del proceso de diseño al edificio, y relegan al “solar” donde éste de ubica a una condición de mero soporte que hay que “aclarar”, nivelar o despejar, pueden derivar en propuestas donde el territorio libre de edificación se abstrae y se presenta como el simple plano de apoyo, como la bandeja plana que da servicio a la arquitectura, sustrayendo al territorio circundante de su propio carácter y de su propia condición de paisaje a respetar, ya dotado de rasgos morfológicos relevantes a considerar.

- La ciudad geológica. Se suele citar el ejemplo del Emerald Necklace de Boston, diseñado por Frederick Law Olmsted a finales del siglo XIX, con su cadena de 7 millas de parques, cuencas fluviales y senderos y carreteras, como uno de los más claros ejemplos del entendimiento de la realidad geológica del núcleo urbano a la hora de planificar su desarrollo. Cursos de agua, vientos dominantes, ciclo solar, topografía, escorrentías, vegetación autóctona, etc., son términos imprescindibles en este planteamiento, que no debieran faltar en las premisas de los planes urbanísticos.

- Ciudades como cultivos. En palabras de Rem Koolhaas, “la arquitectura no es ya el elemento primario del orden urbano; cada vez más el orden viene dado por un delgado plano vegetal horizontal, cada vez más el paisaje es el primer elemento del orden urbano” [2]. Para el arquitecto holandés, es función del urbanismo el “irrigar el territorio con potencial” a la manera como los sistemas agrícolas humanizan el paisaje racionalmente y lo dotan del potencial generar los cultivos. Las actividades urbanas serían los cultivos que un urbanismo de raíces paisajísticas termina haciendo “crecer” en un territorio planificado con el cuidado de un agricultor.

- Los otros convivientes. La atención a los reinos biológicos. Las ciudades son también el biotopo de numerosas especies animales, entre ellas aquellas a las que la actividad urbana expulsa, cuando su convivencia con los humanos fue en otros tiempos provechosa o placentera. Las arquitecturas que construyen esa segunda naturaleza que son las ciudades pueden albergar mecanismos o dispositivos que acojan de nuevo, permanentemente o en tránsito, a especies animales habitualmente expulsadas, pero que puedan enriquecer la cotidianeidad de los ciudadanos, al mismo tiempo que incrementen la biodiversidad de un territorio antaño natural.

- Saludables marchas atrás. La evolución de las actividades urbanas va generando infraestructuras obsoletas para las que la intervención que el cambio de uso genera se sitúa en la rehabilitación o la sustitución de las piezas construidas. No obstante, el cese de una actividad o su obsolescencia puede generar a una oportunidad de desandar el camino andado y dar pie a la renaturalización de algunas porciones de la ciudad. El High Line neoyorkino, con su conversión de las antiguas vías del ferrocarril elevado en un parque lineal, es un buen ejemplo de la capacidad regeneradora de esta postura.

- Designing with nature. Modern cities, and ports in particular, deposit their constructions and infrastructures on the pre-existing natural substrate, generating a sort of concrete mask, under which, however, that substrate survives, with its latent topography, geology and hydrology. Future transformations need not necessarily be based on additions of new layers or new masks, and may, as one of the first options, somehow bring the underlying nature back to light.

- The permeable horizontal plane. The conventional way of urbanizing is based on the generation of impermeable, rigid and flat surfaces, designed mainly for the ease of road mobility, which cut off the hygrothermal exchange with the subsoil. The landscape vision of urban planning, on the contrary, favors the minimization of these impermeable coverings and proposes their possible conversion into new breathable skins, if not open to the natural substratum.

- Praise for slowness and topography. The speed of communications gives meaning to road mobility but not necessarily to pedestrian itineraries, which can be endowed with other attractions in their design: recovering the natural topography and the vernacular ways of walking can enrich the experience of urban space for the pedestrian, especially if, in addition, in the organization of the city, ideas such as that of the “five-minute urbanism”, which aims to concentrate the maximum of daily services within an accessible pedestrian proximity, take precedence.

- The roots of the built. Attention to the pre-existing landscape is also directed to the alterations that constructions cause in the natural substratum and to consider also as an object of the architectural project the sustainable design of these modifications, so that the result does not irreversibly damage the integrity of the natural systems that support the architecture.

- Architectures of light contact. One way of relating respectfully with the natural substrate is to promote architectures that are deposited as delicately as possible on it, with few supports, with unbuilt first floors, or with light technologies, so that buildings can be understood more as reversible facilities with a minimal footprint on the landscape than as heavy and permanent intrusions of it.

- Against the “cleared” site. Attitudes that place the building at the center of the design process, and relegate the “site” where it is located to the condition of a mere support to be leveled or cleared, can lead to proposals where the territory free of buildings is abstracted and presented as a simple support plane, as the flat tray that serves the architecture, removing the surrounding territory from its own character and its own condition of landscape to be respected, already endowed with relevant morphological features to consider.

- The geological city. The example of Boston’s Emerald Necklace, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted at the end of the 19th century, with its 7-mile chain of parks, river basins and trails and roads, is often cited as one of the clearest examples of understanding the geological reality of the urban core when planning its development. Watercourses, prevailing winds, solar cycle, topography, runoff, native vegetation, etc., are essential terms in this approach, which should not be missing in the premises of urban planning.

- Cities as crops. In the words of Rem Koolhaas, “architecture is no longer the primary element of urban order, increasingly urban order is given by a thin horizontal vegetal plane, increasingly landscape is the primary element of urban order” [2]. For the Dutch architect, it is the function of urban planning to “irrigate the territory with potential” in the same way that agricultural systems humanize the landscape rationally and provide it with the potential to generate crops. Urban activities would be the crops that a landscape-rooted urbanism ends up making “grow” in a territory planned with the care of a farmer.

- The other cohabitants. Attention to the biological kingdoms. Cities are also the biotope of numerous animal species, among them those that urban activity expels, when their coexistence with humans was once profitable or pleasant. The architectures that build this second nature that are cities can house mechanisms or devices that welcome back, permanently or in transit, animal species that are habitually expelled, but that can enrich the daily life of citizens, while increasing the biodiversity of a once natural territory.

- Healthy reversals. The evolution of urban activities is generating obsolete infrastructures for which the intervention that the change of use generates is the rehabilitation or replacement of the built parts. However, the cessation of an activity or its obsolescence can generate an opportunity to retrace the path taken and give rise to the renaturalization of certain portions of the city. The New York High Line, with its conversion of the former elevated railroad tracks into a linear park, is a good example of the regenerative capacity of this approach.

Coda. Antes que las ciudades fueron los parques

Coda. Before cities came Parks

La reaparición del paisaje en el imaginario cultural es debida en parte a la notable presencia del medio ambientalismo y la conciencia ecológica global. Para algunos autores, el ejemplo de los jardines de Versalles da un ejemplo señero de cómo el diseño paisajístico puede inspirar un concepto urbano completo. Cuando André Le Nôtre se encuentra el territorio preexistente en Versalles había trazas en el lugar de lo que había sido un territorio de caza y agricultura. Lo que Le Nôtre hace es una especie de “axialización” y domesticación del lugar, de forma que las trazas preexistentes se transmutan en un parque. Un parque que se convirtió en ejemplo para las subsiguientes ciudades barrocas. Había un paisaje preexistente que se transformó en un parque y la forma de este parque creó un efecto espejo y fue la inspiración para las ciudades proyectadas que vinieron después [3].

En una época como la nuestra, donde la atención al medio ambiente se ha situado en el primer lugar de la agenda, las ciudades y sus puertos pueden renaturalizarse y recuperar parte de la naturaleza perdida, o simplemente oculta. Y, como Versalles, anticipar rasgos de la ciudad del futuro.

The reappearance of landscape in the cultural imaginary is due in part to the remarkable presence of environmentalism and global ecological awareness. For some authors, the example of the gardens of Versailles provides a prime example of how landscape design can inspire an entire urban concept. When André Le Nôtre encounters the pre-existing territory at Versailles there were traces on the site of what had been a hunting and agricultural territory. What Le Nôtre does is a kind of “axialization” and domestication of the site, so that the pre-existing traces are transmuted into a park. A park that became an example for subsequent baroque cities. There was a pre-existing landscape that was transformed into a park and the shape of this park created a mirror effect and was the inspiration for the designed cities that came later [3].

In an era like ours, where attention to the environment has moved to the top of the agenda, cities and their harbors can be renaturalized and recover some of the lost, or simply hidden, nature. And in this way, likewise Versailles, they can also provide models for future urbanism.

IMAGEN INICIAL | Zona portuaria donde se ubica la Escuela de Arquitectura. (Fuente: Google Earth).

HEAD IMAGE | Port area where the School of Architecture is located. (Source: Google Earth).

╝

NOTAS

NOTES

[1] Waldheim, Charles (2016), Landscape as Urbanism. A General Theory. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

[2] Koolhaas, Rem (1998), IIT Student Center Competition Address, Illinois Institute of Technology, College of Architecture, Chicago.

[3] Desvigne, Michel, Intermediate Natures. Harvard GSD, Daniel Urban Kiley Lecture, April 10th, 2013 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lHlkLtd6nxw/).

[1] Waldheim, Charles (2016), Landscape as Urbanism. A General Theory. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

[2] Koolhaas, Rem (1998), IIT Student Center Competition Address, Illinois Institute of Technology, College of Architecture, Chicago.

[3] Desvigne, Michel, Intermediate Natures. Harvard GSD, Daniel Urban Kiley Lecture, April 10th, 2013 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lHlkLtd6nxw/).