╔

Le aree di interazione porto-città nei master plan del Sistema Portuale del Mar Ligure Occidentale

Introduzione

Introduction

I vari conflitti legati all’interdipendenza tra porto, città e territorio, in termini di operatività, uso del suolo, confini, trasporto, utilizzo o impatto sull’ambiente, sono una condizione consolidata nelle realtà urbane portuali. A partire dagli anni ‘70 del secolo scorso, lo sviluppo del trasporto marittimo e i conseguenti conflitti con il territorio, hanno portato molte città europee e del mondo ad un progressivo decentramento dei porti in aree extra urbane. Contemporaneamente, nelle aree dei porti storici parzialmente dismesse, in prossimità del centro urbano, sono stati avviati importanti processi di rigenerazione.

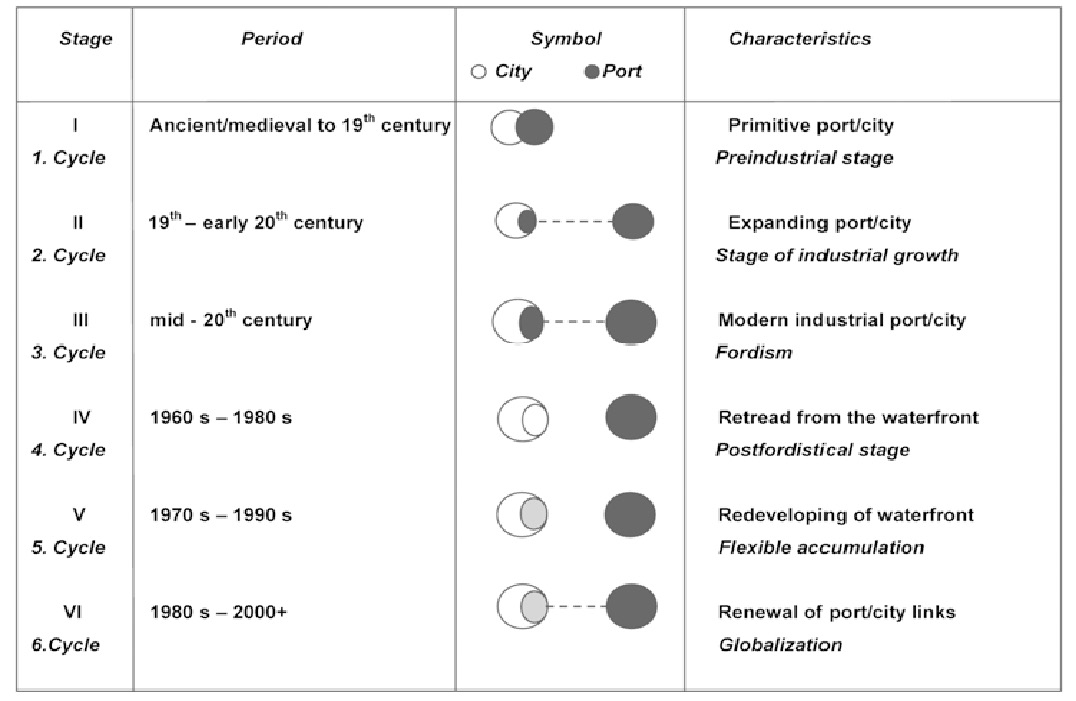

Il famoso schema di Hoyle, che rappresenta le fasi dell’evoluzione dell’interfaccia porto-città (Hoyle, 1989) ha dimostrato il distacco definitivo avvenuto nel corso degli ultimi quarant’anni del Novecento tra i porti — sempre più gateway nazionali — e le città — fulcri delle dinamiche di carattere più locale e regionale. Lo schema ha messo in luce anche le conseguenti dismissioni dei porti storici e la successiva e progressiva riqualificazione del waterfront.

The various conflicts generated by the interdependence between ports, cities, and territories — in terms of operations, land use, borders, transport, their use or impact on the environment — are a well-established feature of port urban realities. Since the 1970s, the development of maritime transport and the resulting conflicts with coastal uses have led many European and global cities to a gradual decentralization of ports into peripheral areas. At the same time, significant regeneration processes have been occurring in areas of partly disused historic ports near city centers.

Hoyle’s renowned scheme, which illustrates the various port-city interface evolution phases (Hoyle, 1989), shows how, during the last forty years of the twentieth century, there has been an irreversible detachment between ports — increasingly considered as national gateways — and cities — serving as hubs for more local and regional-oriented dynamics. The scheme also highlighted the subsequent decommissioning of historic ports and the ongoing, progressive redevelopment of the waterfront.

Fasi dell’evoluzione dell’interfaccia porto-città. (Fonte: Hoyle B.S. (1989) [5, 6]. Rielaborazione dello schema di Hoyle di Moretti, B. (2020).

The stages of the evolution of the port-city interface. (Source: Hoyle B.S., 1989) [5, 6]. Reworking of the Hoyle scheme by Moretti, B., 2020).

Diversamente da questo schema consolidato, in Italia i porti storici si sono ampliati all’interno del sistema urbano, generando talvolta una situazione di stallo e rendendo in generale più complessa l’integrazione tra porto e città o la riqualificazione dei waterfront, che in altri contesti si è invece resa possibile grazie alla nuova disponibilità di spazi. Se lo sviluppo degli spazi del porto in passato derivava dal dibattito politico, di carattere locale e regionale, oggi è sempre più spesso il risultato di principi economici globali, che hanno ulteriormente complicato il dialogo con la città e allontanato un’idea di spazialità condivisa (Savino, 2010; Venosta, Pavia 2012). Il porto, in sostanza, è solo uno degli anelli di una catena di trasporto globale. L’entroterra dei porti italiani, saturo di urbanizzazione, e la fascia costiera, caratterizzata dall’alternanza di materiali urbani e naturali, consentono pochi spazi di manovra per accogliere nuove attività portuali. Lo sviluppo del porto non può avvenire, pertanto, con una disattenzione al territorio in cui si trova e né può basarsi solo su criteri microeconomici o sulle esigenze settoriali legate all’attività degli operatori dei trasporti e della logistica (Ducruet C., 2011).

Unlike this consolidated port development model typical of some regions, Italy’s historic ports have expanded within the urban fabric, often resulting in stagnation, and complicating efforts to integrate ports and cities or redevelop waterfronts, which in other contexts has been made possible thanks to the new availability of spaces. If the development of port spaces in the past derived from regional and local political debate, today it is increasingly driven by global economic principles, which have further hindered shared spatial planning and dialogue with urban areas (Savino, 2010; Venosta, Pavia 2012). The port, in essence, is only one of the links in a global transport chain. The inland areas of Italian ports, saturated with urbanization, and the coastal strip, characterized by the alternation of urban and natural areas, allow limited space for new port activities. Port development must therefore carefully consider the surrounding territory, and cannot be based only on microeconomic criteria or on the sectoral needs linked to the activity of transport and logistics operators (Ducruet C., 2011).

L’evoluzione del porto di Genova nel tempo. (Fonte: https://www.portsofgenoa.com/it/. © DAStU, One Works. Elaborazione di Aisha Kallil Tharayil).

The evolution of the port of Genoa over time. (Source: https://www.portsofgenoa.com/it/. © DAStU, One Works. Elaboration by Aisha Kallil Tharayil).

Il rinnovo del contesto normativo nazionale in materia di porti (Decreto legislativo 169/2016 e D.LGS 232/2017) fa sperare in un cambiamento nei modi di interpretare e costruire la spazialità tra porto e città, che, fino a non molto tempo fa, era mossa dalla generale considerazione del porto come un fatto tecnico concluso, autonomo e settoriale. Si spera inoltre che gli effetti introdotti dalla riforma non siano solamente di tipo gestionale e quantitativo, ma che aprano anche il dibattito sulla qualità degli spazi di contatto tra porto e città.

Ciò permetterà, forse, di allineare i porti italiani alle realtà europee e internazionali, dove un più concreto sviluppo strategico del trasporto marittimo ha generato da tempo importanti processi di rigenerazione urbana e territoriale.

The renewal of the national regulatory framework on ports (Legislative Decree 169/2016 and Legislative Decree 232/2017) offers opportunities for a shift in how the spatial relationship between ports and cities is interpreted and developed, stepping away from the idea of ports as self-contained, independent, and sector-specific technical entities. Hopefully, the reform’s effects will extend beyond management and quantitative measures, fostering a debate on the quality of border spaces between ports and cities.

This could potentially align Italian ports with European and international standards, letting the strategic development of maritime transport drive urban and territorial regeneration processes.

Il caso del Sistema Portuale del Mar Ligure Occidentale

The case of the Western Ligurian Sea Port System

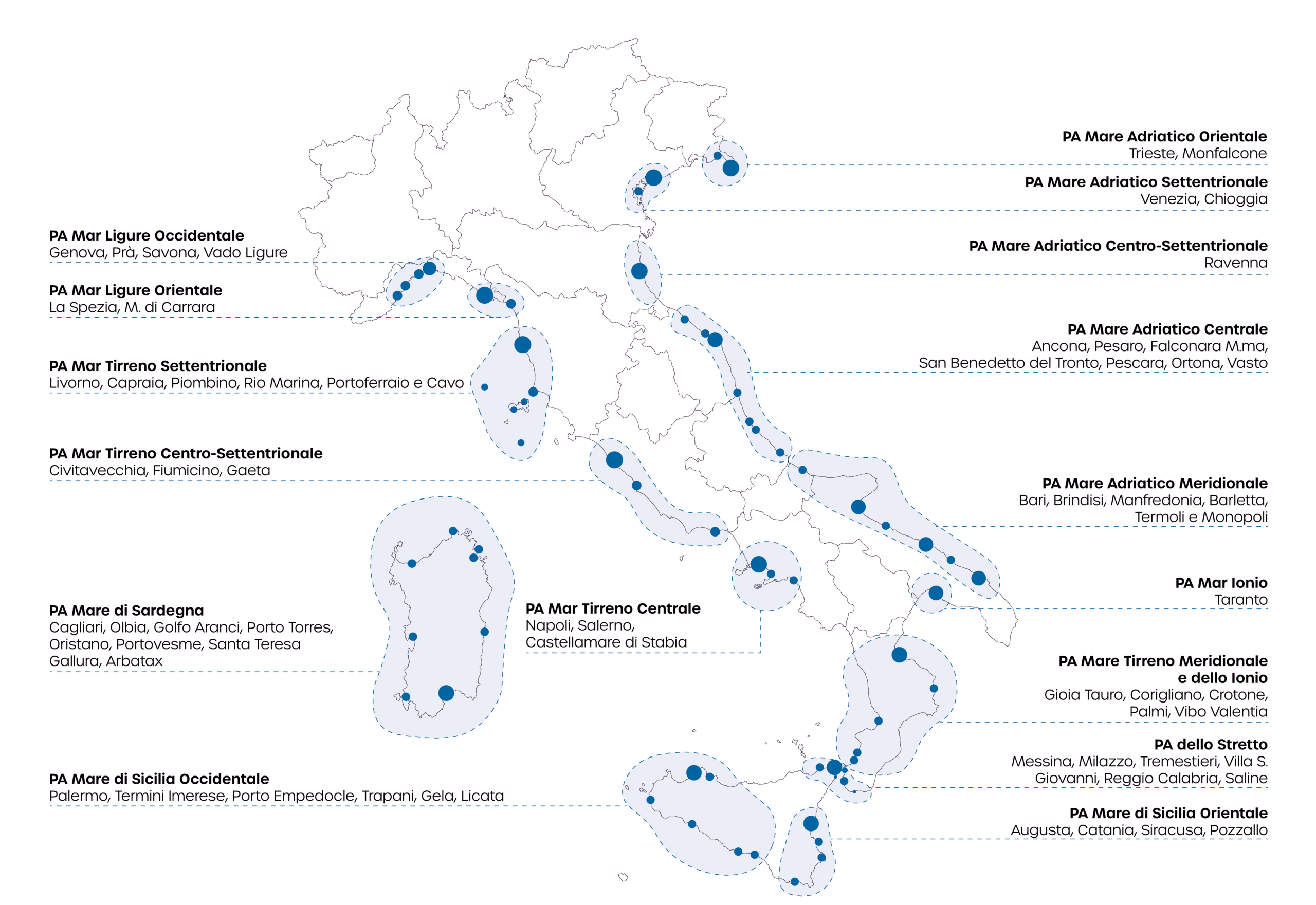

In Italia sono presenti 137 Porti Commerciali Principali [2] e oltre 500 porti turistici e approdi. Secondo la classificazione europea, 14 di questi porti sono definiti core, poiché insistono sui corridoi strategici (3 sul corridoio “Mediterraneo”, 8 su quello “Scandinavo – Mediterraneo”, 3 sul “Baltico – Adriatico”, 1 “Reno – Alpi”); altri 25 sono classificati come comprehensive, collegati a reti interne statali. Nel contesto del Mediterraneo, negli ultimi tempi il sistema portuale italiano si è contratto a causa di una crisi legata alle variazioni nella geografia del transhipment, con il Nord Africa (Westmed) che ha superato l’Italia in termini di volumi gestiti [3].

La necessità di adeguare il Paese agli standard europei, nell’ambito delle reti Core-TEN e del Blue Growth Horizon 2030-50, e di riformare il sistema normativo nazionale per rendere le infrastrutture più connesse ai corridoi strategici europei, ha portato alla riforma della legislazione portuale tra il 2016 e il 2017. Il Decreto Legislativo n.169/2016, oltre ad aver unificato la gestione dei porti, passando dalle 24 Autorità portuali a 16 cluster “di Sistema”, ha articolato la pianificazione portuale su due livelli: uno strategico, rappresentato dal Documento di Pianificazione Strategica di Sistema (DPSS), volto a ripensare in modo integrato e non concorrenziale le portualità vicine; e uno di sviluppo programmatico per il singolo porto, il Piano Regolatore Portuale (PRP) [4]. Questa riforma, sollecitata dall’Europa, mira a promuovere politiche di innovazione strumentale e procedurale, rafforzare le relazioni porto-città e la cooperazione macroregionale, e attuare politiche macro di mitigazione dei cambiamenti climatici, economia circolare e green economy (Prezioso et al.,2027).

Italy has 137 main commercial ports and over 500 marinas and landings [2]. According to the European classification, 14 ports are designated as “core” ports, serving strategic corridors: 3 on the “Mediterranean” corridor, 8 on the “Scandinavian-Mediterranean” corridor, 3 on the “Baltic-Adriatic” and 1 on the “Rhine-Alps” corridor. Additionally, 25 ports are classified as “comprehensive”, connected to internal national networks. Recently, the Italian port system has contracted due to shifts in transhipment geography, with North Africa (Westmed) surpassing Italy in volumes handled [3].

The reform of port legislation between 2016 and 2017 aimed to align the country with European standards, particularly within the Core-TEN networks and the Blue Growth Horizon 2030-50. Legislative Decree no. 169/2016 unified port management from 24 to 16 “System” clusters and introduced a two-tier port planning approach: a strategic level via the Strategic System Planning Document (DPSS) for integrated port development, and a programmatic level through the Port Master Plan (PRP) [4]. This reform was driven by European prompts to foster innovation, enhance port-city relations, macro-regional cooperation, and support climate change mitigation, circular, and green economies (Prezioso et al., 2027).

Il terminal container del Porto di Genova. (© Michele Pugliese, 2023).

The container terminal at the Port of Genoa. (© Michele Pugliese, 2023).

L’attuazione del PNRR e, nel caso ligure, anche delle misure straordinarie adottate dopo il crollo del ponte Morandi, hanno accelerato i processi di programmazione e progettazione degli interventi infrastrutturali, che spesso sono risultati frammentari e poco integrati in una visione complessiva. In Liguria, gli interventi programmati e in corso negli ambiti portuali rispondono a logiche e strategie di scala nazionale e internazionale, confrontandosi con un territorio complesso dal punto di vista geomorfologico e urbanistico. Per questo motivo, prima di definire la strategia del nuovo Piano Regolatore del Sistema Portuale del Mar Ligure Occidentale, è stato fondamentale analizzare e raccordare le traiettorie di numerosi piani e progetti in corso, coinvolgendo l’intera dimensione urbana e territoriale in uno scenario di riferimento complessivo (Nifosì, C., Pintus, F., Pugliese, M., 2025).

The implementation of the PNRR, and in the Ligurian case, also the extraordinary measures adopted following the collapse of the Morandi bridge, have accelerated the planning and design processes of infrastructure interventions, which have often been fragmented and poorly integrated into an overarching vision. In Liguria, the planned and ongoing interventions in port areas respond to strategies at both national and international levels, addressing a complex territory from a geomorphological and urban perspective. Consequently, prior to defining the strategy for the new Master Plan of the Port System of the Western Ligurian Sea, it was essential to analyze and connect the trajectories of numerous ongoing plans and projects, assessing the entire urban and territorial context within an overall reference scenario (Nifosì, C., Pintus, F., Pugliese, M., 2025).

La geografia dei cluster portuali italiani dopo la riforma nazionale del sistema portuale nel 2026. (© DAStU, One Works).

The Geography of Italian Port Clusters after the national reform of the port system in 2026. (© DAStU, One Works).

Verso una maggiore collaborazione Porto-città

Towards greater Port-city collaboration

Le Linee guida per la redazione dei Piani Regolatori di Sistema Portuale (PRdSP), elaborate dal Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti nel marzo 2017, disciplinano gli ambiti dei distinti porti facenti parte del sistema in due sotto-ambiti: a) porto operativo; b) interazione città-porto.

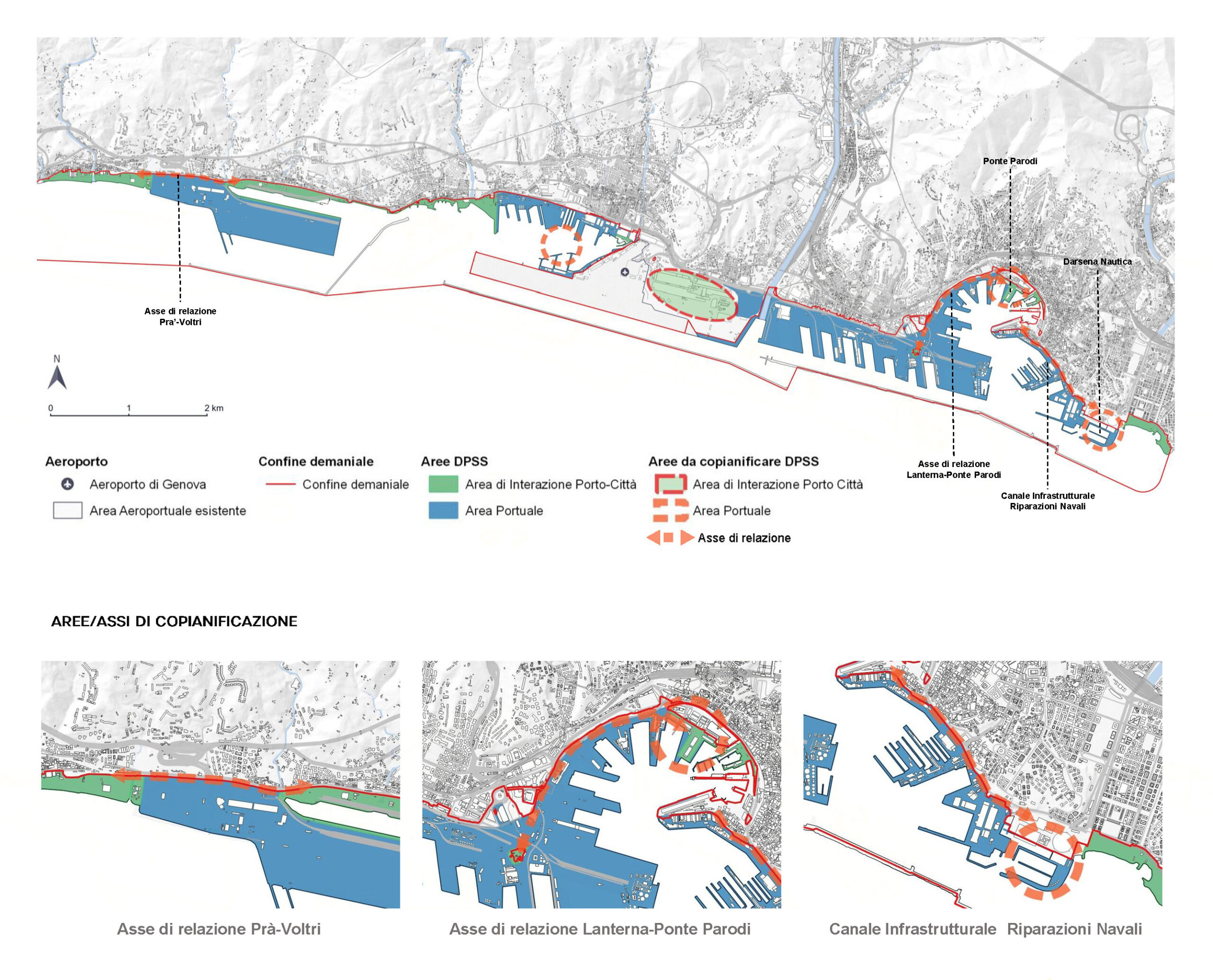

Il Documento di Pianificazione Strategica di Sistema (DPSS) redatto dall’Autorità di Sistema Portuale (AdSP) del Mar Ligure Occidentale nell’Aprile 2021, costituisce il primo documento che guarda al territorio portuale del Mar Ligure Occidentale in una logica integrata, e orienta la pianificazione dei singoli scali che sarà sviluppata attraverso i Piani Regolatori Portuali (PRP).

Rispetto al tema della “collaborazione” tra porto e città, le principali novità introdotte dal DPSS sono le indicazioni per le cosiddette aree retroportuali e di interazione porto-città. L’idea di “interazione” va intesa anzitutto come pianificazione condivisa tra tutti gli attori coinvolti, in primis l’Autorità Portuale e il Comune, ma anche con altri enti, come ad esempio la Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio. L’obiettivo è identificare insieme e definire la programmazione di quegli ambiti strategici che sono strettamente legati sia alle funzioni portuali che al contesto urbano. Il documento propone le seguenti categorie interpretative per questi ambiti, che sono:

- Aree portuali: zone operative del porto, che saranno oggetto di pianificazione più dettagliata da parte dell’AdSP nei successivi PRP di scalo.

- Aree portuali da co-pianificare: zone demaniali di interesse operativo portuale, per le quali si ritiene importante avviare o rafforzare processi di pianificazione condivisa.

- Aree di interazione porto-città: zone demaniali di carattere urbano, che saranno pianificate principalmente dal Comune.

- Aree di interazione porto-città da co-pianificare: zone che si trovano oltre le aree demaniali, di grande interesse sia portuale sia urbano, sulle quali bisogna avviare percorsi di co-pianificazione che coinvolgano tutti i soggetti interessati, come i Comuni, l’AdSP e altri enti competenti.

Per quanto riguarda il Porto di Genova, il DPSS indica alcune zone specifiche da co-pianificare, tra cui: l’asse di relazione Prà-Pegli; Sestri; l’asse di relazione tra Lanterna e Ponte Parodi; Ponte Parodi; il canale infrastrutturale delle riparazioni navali; la Darsena Nautica.

Analogamente, nel DPSS sono state individuate le aree portuali da co-pianificare del Porto di Savona e Vado Ligure. A Savona l’asse di relazione Fascia costiera di levante e il piazzale prospiciente il Priamar; a Vado Ligure, l’asse di relazione Porto Di Vado e Punta dell’Asino.

Le funzioni compatibili all’interno della relazione città porto sono da ricercare nelle varie attività destinate ai passeggeri (ro-pax, crocieristica, turistica e da diporto, peschereccia), nei vari servizi al porto (uffici portuali), negli spazi e servizi collettivi (viabilità, parcheggi…) e in particolare, nei vari usi urbani (spazi commerciali, direzionali, residenziali, culturali e rappresentativi, aree verdi, misti) di interesse comune tra porto e città.

Nella definizione di questi ambiti, un ruolo di rilievo va riservato anche agli “innesti urbani”, direttrici di percorso che garantiscono il legame fisico e sociale fra la città e le aree portuali più permeabili e compatibili con i flussi e le attività della città. Nel caso di innesti urbani che si relazionano con il porto operativo — spesso interdetto dalle barriere doganali alla fruizione dei non addetti — questi si costituiscono anche come correlazioni visive fra la città e il mare.

Established by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport in March 2017, the Guidelines for the drafting of Port System Master Plans (PRdSP) identify two types of port zones: a) operational port; b) city-port interaction areas.

The Strategic System Planning Document (DPSS) compiled in April 2021 by the Port System Authority (PSA) of the Western Ligurian Sea, is the first document that conceives its own port territory holistically and provides guidelines for the individual harbours’ Port Regulatory Master Plans (PRP).

Innovatively addressing the theme of “collaboration” between port and city, the DPSS identifies “inland port areas” and “port-city interface areas”. Here, shared planning is required between all actors involved, first and foremost Port Authorities and Municipalities, as well as other entities such as Conservation bodies. The goal is to jointly identify strategic areas closely linked to both port uses and urban context, eventually defining their planning rules and objectives. The DPSS divides these areas into four categories:

- Port areas: harbour operational areas, which will be subject to more detailed planning by the Port Authority in subsequent phases.

- Port areas to be co-planned: state-owned areas of port operational interest, where shared planning processes should be initiated or strengthened.

- Port-city interface areas: urban state-owned areas, which will be planned mainly by the Municipality.

- Port-city interface areas to be co-planned: areas located beyond the State ownership border, that are of great interest to both the port and the city, where co-planning processes must be initiated with the involvement of all stakeholders, such as Municipalities, the Port Authority, and other competent bodies.

Within the Port of Genoa, the DPSS identifies specific areas for co-planning, including: the Prà-Pegli axis; Sestri; the Lanterna-Ponte Parodi axis; Ponte Parodi; the shipyard channel; the Darsena Nautica.

Within the Port of Savona and Vado Ligure, these include the eastern coastal strip and the square overlooking Priamar in Savona; the axis between Porto di Vado and Punta dell’Asino in Vado Ligure.

These city-port relationship areas may include uses aimed at passengers (ro-pax, cruise terminals, marinas, fishing), port services (port offices), communal spaces and amenities (roads, parking), and notably, various real estate uses (commercial, office, residential, cultural, and representative spaces, green areas, mixed-use) that are of mutual interest to both the harbour and the city.

In defining these areas, significant emphasis must also be placed on “urban connections” — routes that ensure physical and social links with more permeable and compatible port and city areas, encouraging flows and activities. Within port areas — that are often not accessible to the public — these urban connections also serve as visual links between the city and the sea.

Aree portuali di Co-pianificazione, Genova. (Fonte: DPSS. Rielaborazione © One Works su schema DPSS Mar Ligure Occidentale).

Co-planning Port Areas, Genoa. (Source: DPSS. Re-elaboration © One Works on the Western Ligurian Sea DPSS scheme).

Strategia per l’asse di relazione porto-città Lanterna-Parodi a Genova

Strategy for the Lanterna-Parodi port-city axis in Genova

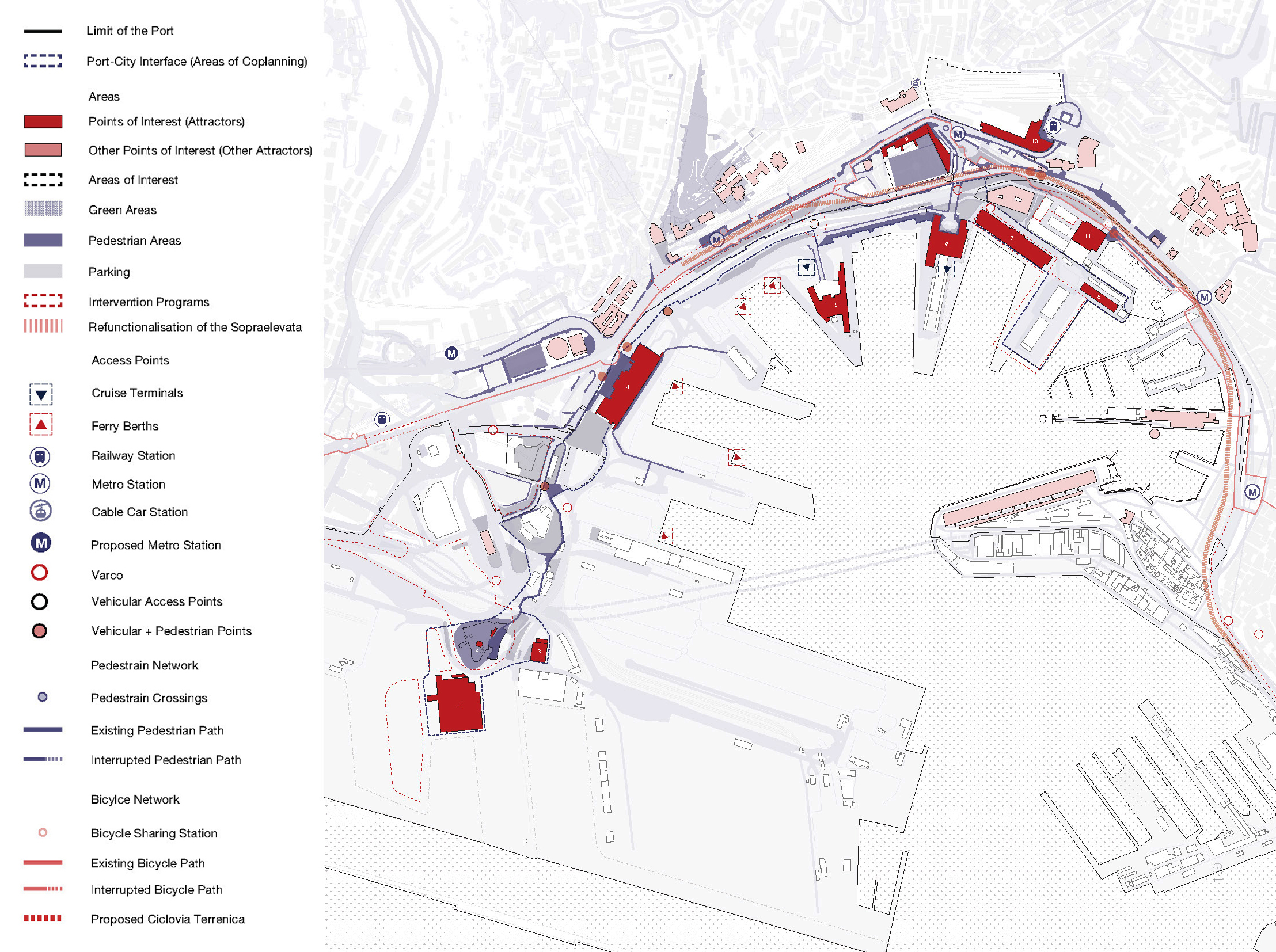

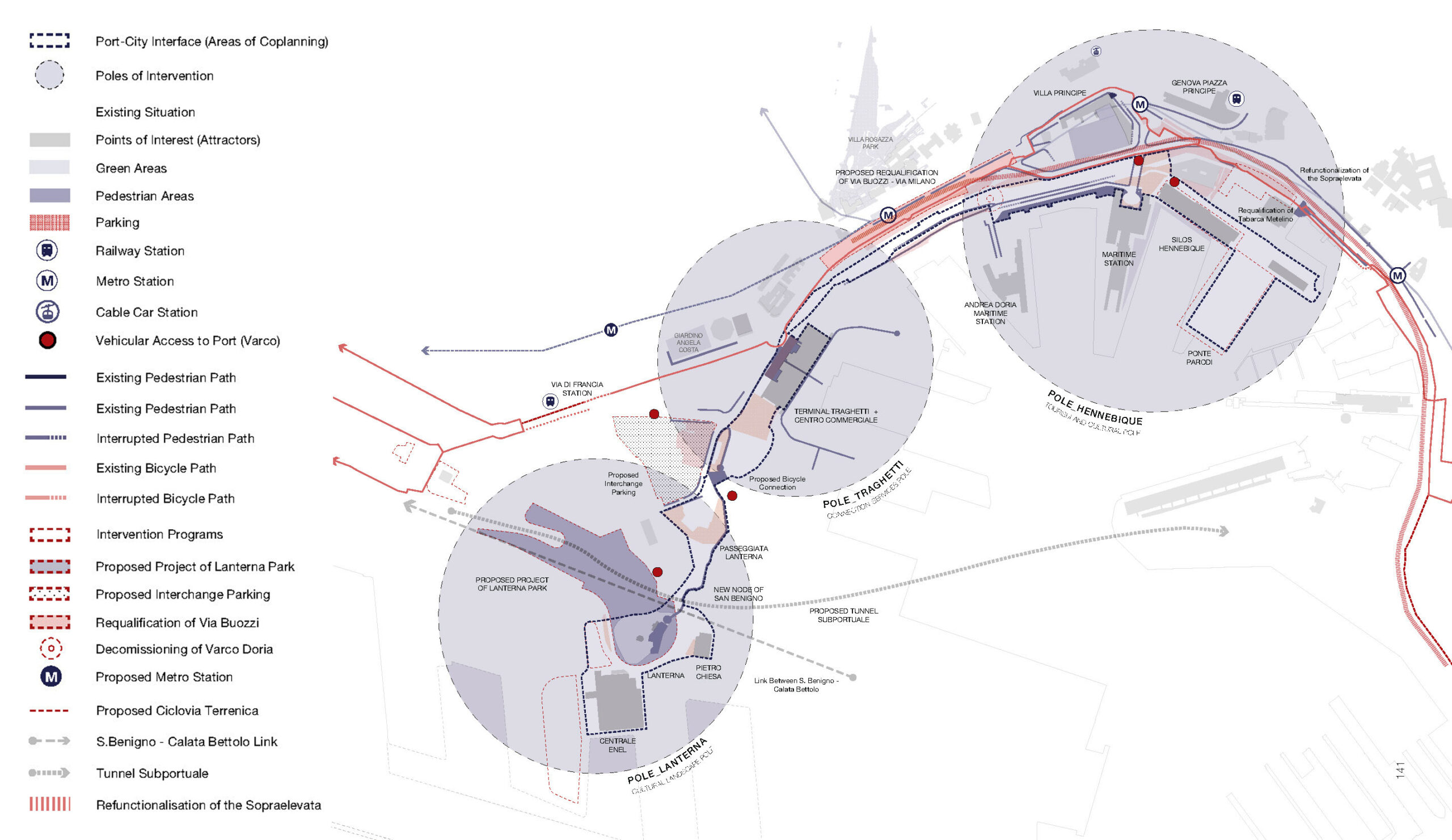

Ad esemplificazione della strategia preliminare proposta nei Piani regolatori portuali di Genova e Savona-Vado Ligure, negli assi strategici di relazione porto-città individuati dal DPSS si descrivono i poli tematici di sviluppo previsti dal PRP per l’asse Lanterna-Parodi a Genova. Uno dei principali obiettivi del PRP è avviare processi di riqualificazione all’interno degli archi urbano-portuali e garantire, all’interno di ciascun polo dell’asse, una “continuità” di spazi pubblici di qualità.

I tre poli tematici di sviluppo individuati per l’Asse di relazione Lanterna-Parodi a Genova sono quello a vocazione culturale-ambientale della Lanterna; quello a vocazione commerciale dei Terminal traghetti; quello culturale-turistico Hennebique-Principe.

Il Polo della Lanterna di Genova è un’area di grande trasformazione, che unisce passato e futuro. Al centro di questo progetto ci sono interventi di riqualificazione del parco della Lanterna (compensazione del tunnel subportuale), del Nodo di San Benigno e del collegamento tra quest’ultimo e Colato Bettolo, della rigenerazione di edifici storici dismessi, come la centrale ENEL e il Palazzo Pietro Chiesa, testimonianze importanti dell’industria energetica e del passato portuale di Genova.

Un altro elemento chiave di questa zona è la “Passeggiata della Lanterna”, che è il simbolo della città con il terminal dei traghetti. Costruita nel 2001, questa passeggiata offre una vista sul porto e sulla città, ma ad oggi presenta condizioni di degrado e ampi margini di miglioramento. L’idea è di ampliarla, arricchirla con alberature e nuovi servizi, integrarla puntualmente con nuovi nodi di interscambio modale (mezzi pubblici, car-bike sharing) per favorire una mobilità più ecologica, migliorare i punti di contatto visivo del paesaggio del porto e del mare, moltiplicare i punti di accesso alla linea di costa.

L’obiettivo generale è sviluppare le attività operative del porto lungo le banchine, lasciando le funzioni urbane e di svago più in alto, collegando il tutto con percorsi aerei e continui lungo la passeggiata. In questo modo, si vogliono creare spazi più vivibili, in armonia tra porto, città e verde, valorizzando il simbolo della Lanterna come punto di riferimento.

Un secondo grande polo riguarda invece il sistema commerciale e dei servizi, con il Terminal dei Tragetti e il centro commerciale lungo via Milano. Qui si prevedono interventi di miglioramento dei collegamenti, come il prolungamento della metropolitana, nuove piste ciclabili, e parcheggi di scambio per facilitare l’accesso e la mobilità sostenibile. Si punta anche a riqualificare gli spazi pubblici e a rendere più funzionali e belli i percorsi tra il porto e le aree urbane.

Infine, il terzo polo è quello turistico-culturale dell’Hennebique-Principe, che si sviluppa lungo il Porto antico. Questo spazio ospita importanti edifici storici, come la facoltà di Economia, l’Istituto Nautico, e la Villa del Principe, e si collega tramite strade carrabili come via Buozzi e il Viadotto Cesare Imperiale. L’obiettivo è di riqualificare queste vie e i porticcioli, rendendo più accessibili e vivibili le aree di attrazione, con progetti di restauro, nuove funzioni e spazi verdi.

As an example of the preliminary strategy proposed in the PRPs of Genoa and Savona-Vado Ligure, the Lanterna-Parodi strategic axis in Genoa (identified by the DPSS) identifies thematic development poles. One of the main objectives of the PRP is to initiate regeneration processes within the urban-port arches, guaranteeing, within each pole along the axis, a “continuity” of quality public spaces.

Along the Lanterna-Parodi axis, the following poles are therefore identified: a cultural-environmental hub around the Lanterna; a commercial pole around the Ferry Terminals; a cultural/tourist-oriented hub at Hennebique-Principe.

The Polo della Lanterna in Genoa is an area of great transformation, which combines past and future. At the heart of this project are the redevelopment of the Lanterna park (compensation for the subport tunnel), the San Benigno Node and the connection between the latter and Calata Bettolo, the regeneration of disused historical buildings, such as the ENEL power plant and Palazzo Pietro Chiesa, important testimonies of the energy industry and Genoa’s port past.

Another key element of this area is the Lanterna Promenade, the Lanterna being an icon for the city, together with the ferry terminal. Built in 2001, this promenade offers views of the harbor and the city; however, it is currently in a state of decay, and there is definitely room for improvement. The idea is to expand it, enrich it with trees and new services, and integrate it punctually with new modal interchange nodes (public transport, car-bike sharing) to promote more ecological mobility, improve the visual points of contact towards the port and sea landscape, and increase the access points to the coastline.

The general objective is to maintain the operational activities of the port along the quays, concentrating the urban and leisure uses on a higher level, connecting everything through elevated and continuous paths along the promenade. The intention is to create more livable spaces, in harmony with the port, the city, and the greenery, enhancing the iconic Lantern as a point of reference.

A second large pole concerns the commercial and service system by the Ferry Boat Terminal and the shopping center along Via Milano. Here, a series of interventions are planned to improve connections, including the extension of the subway, new cycle paths, and park-and-ride plots to facilitate access and sustainable mobility. The aim is also to redevelop public spaces and make the paths between the port and urban areas more functional and beautiful.

Lastly, the tourist-cultural pole of Hennebique-Principe is located along the Old Port. This space houses important historical buildings, such as the Faculty of Economics, the Nautical Institute, and the Villa del Principe, and is connected via driveways such as Via Buozzi and the Cesare Imperiale Viaduct. The goal is to redevelop these streets and marinas, making these areas of attraction more accessible and livable, through regeneration projects, new uses, and green spaces.

Scenario di riferimento dell’asse di relazione Lanterna-Ponte Parodi. (© One-Works; DAStU).

Reference scenario of the Lanterna-Parodi Bridge relationship axis. (© One-Works; DAStU).

I poli tematici di sviluppo dell’asse di relazione Lanterna-Ponte Parodi. (© One-Works; DAStU).

The thematic poles of development of the Lanterna-Parodi Bridge relationship axis. (© One-Works; DAStU).

Osservazioni finali

Final Remarks

L’ Italia presenta un numero rilevante di città-porto di piccola e media dimensione che, limitate nelle possibilità di espansione, per essere competitive sono chiamate ad elaborare strategie di collaborazione tra sistemi portuali, e tra questi e la città, la città e il territorio.

Un porto competitivo può contribuire al miglioramento delle condizioni della città e del territorio attraverso l’indotto economico che l’attività portuale riversa nell’inland, generando ricchezza e occupazione, ma anche attraverso l’indotto derivato da attività di riconversione degli areali e degli immobili dismessi o sottoutilizzati del porto, in nuovi waterfront urbani e servizi per la collettività (Nifosì, De Angelis F. 2023).

Viceversa, il pubblico e la città possono sostenere il porto in diversi modi: con una buona pianificazione urbana “di terra” integrata a quella del porto; attraverso la partecipazione degli Enti pubblici di Governo della città e del territorio alla redazione dei piani di sviluppo portuale; e tramite il coinvolgimento del Porto nei vari piani di sviluppo strategico urbani e territoriali.

Italy has a significant number of small and medium-sized port cities that have limited possibilities of expansion. To be competitive, they must develop collaboration strategies between different port systems, and between these and their hosting cities, the cities and their surrounding territory.

A competitive port can contribute to improving the conditions of its hosting city and its wider context through the economic spin-offs that port activity pours into the inland, generating wealth and employment, but also through the induced activities derived from the conversion of the areas and abandoned or underused buildings of the port, into new urban waterfronts and services for the community (Nifosì, De Angelis F. 2023).

Conversely, public entities and cities can support harbors in various ways: through effective land-use urban planning integrated with that of the port; by involving municipal and regional public authorities in drafting port development plans; and by engaging ports in various urban and territorial strategic development plans.

IMMAGINE INIZIALE | Veduta del porto di Genova e della città sullo sfondo. (© Michele Pugliese, 2023).

HEAD IMAGE | A view of the port of Genoa and the city in the background. (© Michele Pugliese, 2023).

╝

NOTE

NOTES

[1] Il raggruppamento Temporaneo di Impresa responsabile (RTI) dei nuovi piani è composto da: BPT infrastrutture – Capogruppo; Acquatecno – pianificazione marittima; One Works (con il supporto del Dipartimento di Architettura e Studi Urbani e Craft del Politecnico di Milano) – analisi urbanistica e pianificazione/indirizzi di progettazione delle aree di co-pianificazione porto-città); KPMG – analisi socioeconomica e scenario di traffico marittimi e terrestri; Systematica – analisi dei trasporti; Ambiente – analisi ambientale.

[2] https://www.istat.it/comunicato-stampa/trasporto-marittimo-anni-2019-2020-anticipazioni-gennaio-settembre-2021/.

[3] Ferrari, C., Tei, A., & Merk, O., (2015), “The Governance and Regulation of Ports: The Case of Italy”, Oced, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/dp201501.pdf/. pag. 17.

[4] https://iris.unirc.it/retrieve/e2047588-f732-7e24-e053-6605fe0afb29/Bellamacina%20Dora.pdf/.

[5] Hoyle, B.S. “The port—City interface: Trends, problems and examples”, in Geoforum, Volume 20, Issue 4, 1989, Pages 429-435, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(89)90026-2.

[6] Moretti, B. (2020). Beyond the port city: The condition of Portuality and the threshold concept. Jovis Verlag GmbH. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353583517_Beyond_the_Port_City_The_Condition_of_Portuality_and_the_Threshold_Concept/.

[1] The Temporary Group Companies responsible (RTI) for the new plans consist of: BPT Infrastrutture – Parent Company; Acquatecno – maritime planning; One Works (with support of the Department of Architecture, Urban Studies, and Craft within the Politecnico di Milano) – urban analysis and planning/design guidelines for port-city co-planning areas; KPMG – socio-economic analysis and maritime and land traffic scenarios; Systematica – transport analysis; Environment – environmental analysis.

[2] https://www.istat.it/comunicato-stampa/trasporto-marittimo-anni-2019-2020-anticipazioni-gennaio-settembre-2021/.

[3] Ferrari, C., Tei, A., & Merk, O., (2015), “The Governance and Regulation of Ports: The Case of Italy”, Oced, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/dp201501.pdf/. pag. 17.

[4] https://iris.unirc.it/retrieve/e2047588-f732-7e24-e053-6605fe0afb29/Bellamacina%20Dora.pdf/.

[5] Hoyle, B.S. “The port—City interface: Trends, problems and examples”, in Geoforum, Volume 20, Issue 4, 1989, Pages 429-435, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(89)90026-2.

[6] Moretti, B. (2020). Beyond the port city: The condition of Portuality and the threshold concept. Jovis Verlag GmbH. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353583517_Beyond_the_Port_City_The_Condition_of_Portuality_and_the_Threshold_Concept/.