╔

Waterfront Palermo: un viaggio lungo venti anni tra tempeste e approdi sicuri

Sono già passati venti anni dall’inizio del lungo viaggio che Palermo ha coraggiosamente e faticosamente intrapreso per tornare ad affacciarsi sul mare, per reimmergersi nel liquido amniotico che l’ha generata, per riavere un porto propulsore di potenti economie e generatore di quotidiana bellezza, insomma, per riconquistare un futuro liquido di “città tutta porto”. Il caso di Palermo rappresenta un’esperienza paradigmatica di rigenerazione dei waterfront avviata, con progressiva consapevolezza e operatività, a partire dal 2005, con l’obiettivo strategico di riconnettere la città al suo mare e riattivare la funzione del porto commerciale, dei porti turistici e delle estese aree costiere come interfaccia tra la propulsione economica e la generazione di qualità urbana. Il fronte a mare urbano si estende per 26 km, dalla borgata di Acqua dei Corsari a Vergine Maria, fino ai quartieri balneari di Mondello e Sferracavallo, attraversando una permanente simbiosi tra città e mare, tra artificiale e naturale, tra lapideo e liquido.

L’approccio metodologico adottato, in linea con le più mature esperienze di riqualificazione dei waterfront urbani maturate a livello internazionale (Giovinazzi, Moretti, 2010), si fonda sul “paradigma della città liquida” (Carta, 2018; Carta, Ronsivalle, 2016; Carta, La Greca, Ronsivalle, Lino, 2025). Un modello concettuale che considera il waterfront non solo come un’area funzionale, ma come una componente urbana/umana in grado di generare nuove economie e dinamiche di sviluppo, connettendo la città alle relazioni globali e migliorando la qualità dello spazio urbano (Hein, 2014): una dimensione che connette lo spazio concepito dalle istituzioni, lo spazio vissuto dalle comunità e lo spazio percepito dai fruitori. A Palermo, quindi, le aree portuali, peri-portuali, marittime urbane e costiere naturali sono riconfigurate in una nuova, creativa e complessiva idea di città (Carta, 2023) come una fascia di luoghi densi di attività e porosi ai flussi locali e globali: un arcipelago di porte e di vestiboli, di centralità e di interfacce.

Twenty years have already passed since the beginning of the long journey that Palermo has courageously—and laboriously—undertaken to return to facing the sea; to be re-immersed in the amniotic fluid that generated it; to regain a port that can propel powerful economies and generate everyday beauty; in short, to reclaim a liquid future as a “city entirely port.” The Palermo case represents a paradigmatic experience of waterfront regeneration, initiated with progressively greater awareness and operability starting in 2005, with the strategic objective of reconnecting the city to its sea and reactivating the function of the commercial port, the tourist harbors, and the extensive coastal areas as an interface between economic propulsion and the production of urban quality. The urban seafront extends for 26 km, from the hamlet of Acqua dei Corsari to Vergine Maria, up to the seaside districts of Mondello and Sferracavallo, traversing a permanent symbiosis between city and sea, between the artificial and the natural, between the lithic and the liquid.

The methodological approach adopted—consistent with the most mature international experiences in urban waterfront redevelopment (Giovinazzi, Moretti, 2010)—is grounded in the “fluid city paradigm” (Carta, 2018; Carta, Ronsivalle, 2016; Carta, La Greca, Ronsivalle, Lino, 2025). This is a conceptual model that considers the waterfront not merely as a functional area, but as an urban/human component capable of generating new economies and development dynamics, connecting the city to global relations and improving the quality of urban space (Hein, 2014): a dimension that links space conceived by institutions, space lived by communities, and space perceived by users. In Palermo, therefore, port areas, peri-port areas, urban maritime zones and natural coastal environments are reconfigured into a new, creative, and comprehensive idea of the city (Carta, 2023), as a band of places dense with activities and porous to local and global flows: an archipelago of gates and vestibules, of centralities and interfaces.

Progettare la città liquida

Designing the Fluid City

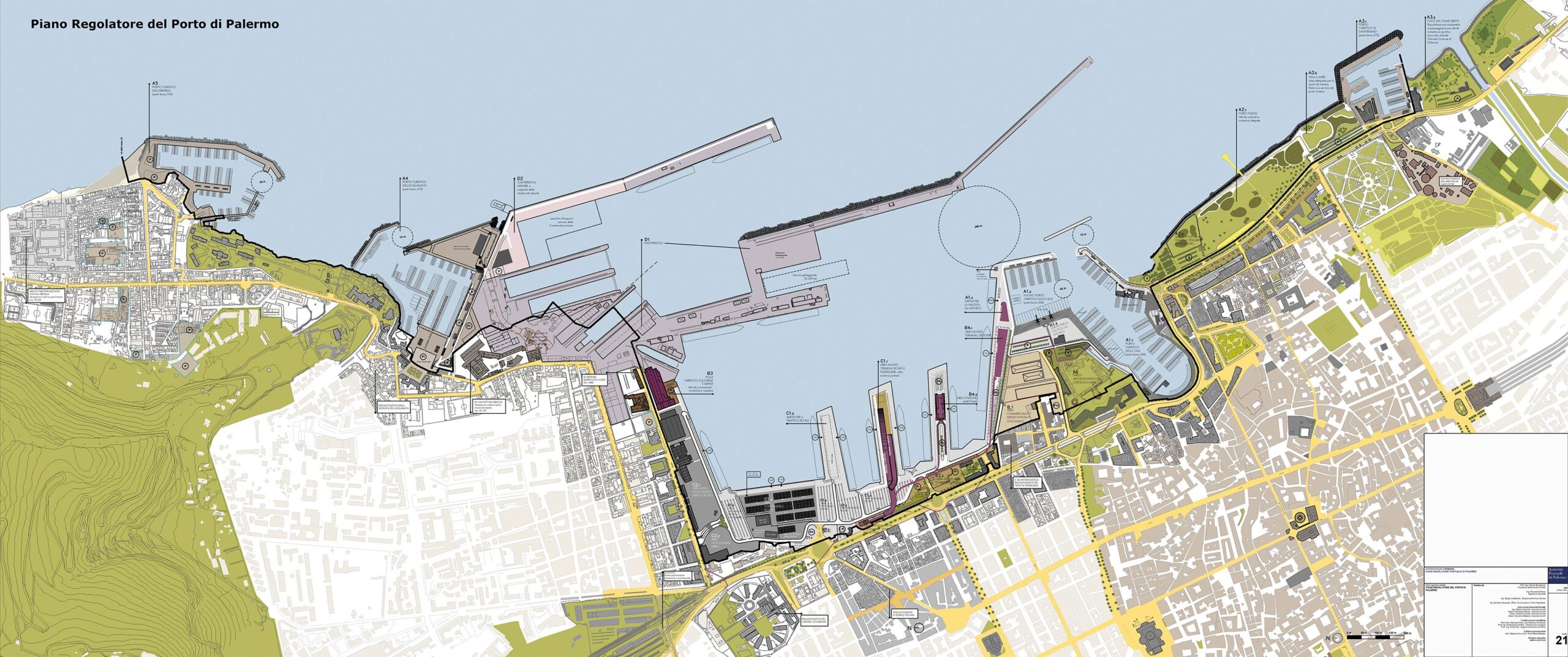

Il primo passo concreto della progettazione della città liquida è stato il Piano Regolatore Portuale (PRP), redatto da chi scrive nel 2008 per l’Autorità Portuale presieduta da Antonio Bevilacqua e approvato solo nel 2018 sotto la presidenza di Pasqualino Monti. Esso non è stato concepito come un mero strumento regolativo tradizionale, ma come uno strumento complesso con funzioni di scenario, indirizzo e progetto, anticipando alcune delle più recenti innovazioni in termini di pianificazione portuale. La sua missione principale è stata quella di ricomporre il senso e l’efficacia del sistema portuale, riconnettendo porto e città attraverso la definizione di opportune interfacce città-porto e aree bersaglio, aree permeabili e osmotiche da destinare alla vita urbana, in sinergia con lo sviluppo delle funzioni portuali e le necessità di sicurezza.

Il modello applicato distingue l’area portuale in tre tipologie con diverso grado di apertura verso la città:

- il porto liquido è l’area totalmente aperta e ramificata nel tessuto urbano (es. Cala, Molo Trapezoidale), dedicata alla nautica da diporto, servizi culturali e tempo libero;

- il porto permeabile è costituito dalle aree di interscambio con la città (es. area crocieristica e passeggeri della Banchina Sammuzzo e del Molo Vittorio Veneto), la cui relazione è filtrata da esigenze di sicurezza, ma assicurata da vaste aree di rigenerazione urbana che fungono da collante (es. Molo Trapezoidale);

- il porto rigido è la vera e propria macchina portuale (es. Banchina Quattroventi e Cantieri Navali), che deve rimanere impermeabile alle contaminazioni urbane, se non quelle strettamente funzionali, per garantirne efficienza e sicurezza.

The first concrete step in designing the fluid city was the Port Master Plan (Piano Regolatore Portuale—PRP), drafted by the author in 2008 for the Port Authority chaired by Antonio Bevilacqua and approved only in 2018 under the presidency of Pasqualino Monti. It was not conceived as a mere traditional regulatory instrument, but as a complex tool with scenario-building, guidance, and design functions, anticipating some of the most recent innovations in port planning. Its primary mission was to restore the meaning and effectiveness of the port system by reconnecting port and city through the definition of appropriate city–port interfaces and target areas—permeable and osmotic zones to be devoted to urban life, in synergy with the development of port functions and security requirements.

The applied model distinguishes the port area into three types, with different degrees of openness toward the city:

- the fluid port is the area totally open and branching into the urban fabric (e.g., Cala, Molo Trapezoidale), devoted to recreational boating, cultural services, and leisure;

- the permeable port consists of interchange areas with the city (e.g., the cruise and passenger zone of Banchina Sammuzzo and Molo Vittorio Veneto), whose relationship is filtered by security needs but ensured by large urban regeneration areas that act as connective tissue (e.g., Molo Trapezoidale);

- the rigid port is the port machine proper (e.g., Banchina Quattroventi and the shipyards), which must remain impermeable to urban contaminations—except for strictly functional ones—in order to guarantee efficiency and safety.

Palermo. Il Piano Regolatore Portuale approvato nel 2018. (Fonte: Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mare di Sicilia Occidentale).

Palermo. The Port Master Plan approved in 2018. (Source: Western Sicily Port Authority – AdSPMSO).

Nel perimetro concettuale e spaziale di queste tre configurazioni portuali possono essere riconosciuti alcuni peculiari punti di forza:

- l’integrazione funzionale e spaziale: il piano ha consentito il riordino delle funzioni portuali per specializzare gli spazi e riservarne alcuni a nuove funzioni urbane;

- la generazione di nuovo spazio pubblico “aumentato”, liquido, aperto, ibrido, poroso e creativo, con interventi iconici come il Palermo Marina Yachting;

- la moltiplicazione di capitale urbano: il waterfront si configura come un moltiplicatore di capitale urbano e propulsore di sviluppo sostenibile. Il Molo Trapezoidale, ad esempio, genera valore immobiliare, commerciale e turistico.

Within the conceptual and spatial perimeter of these three port configurations, some distinctive strengths can be identified:

- functional and spatial integration: the plan enabled the reordering of port functions, specializing spaces and reserving some for new urban functions;

- the generation of new “augmented” public space: liquid, open, hybrid, porous, and creative, with iconic interventions such as Palermo Marina Yachting;

- the multiplication of urban capital: the waterfront is configured as a multiplier of urban capital and a driver of sustainable development. Molo Trapezoidale, for example, generates real-estate, commercial, and tourism value.

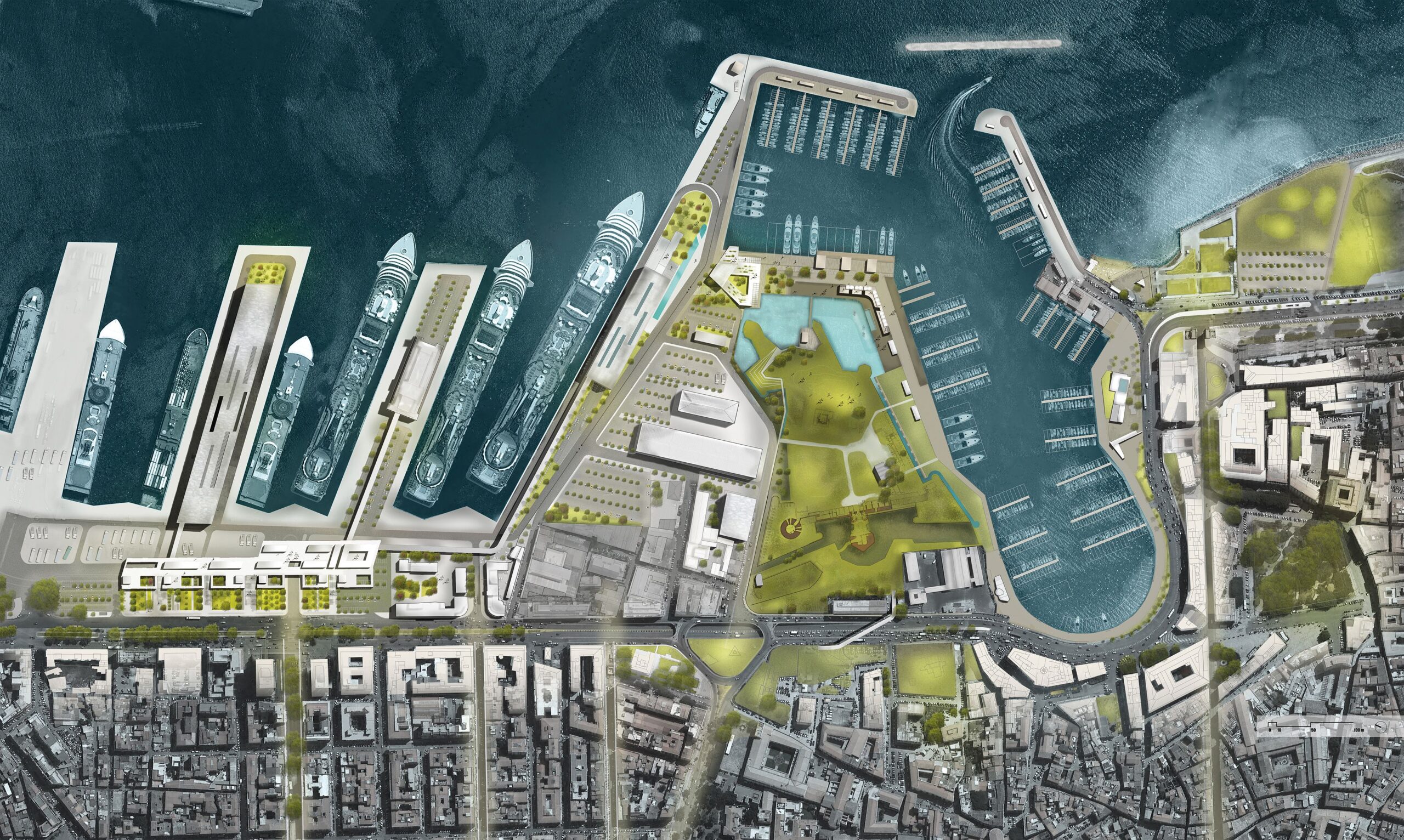

Piano di dettaglio waterfront centrale di Palermo. (Fonte: Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mare di Sicilia Occidentale).

Detailed plan of Palermo’s central waterfront. (Source: Western Sicily Port Authority – AdSPMSO).

Naturalmente, non devono essere taciute le criticità e le barriere che hanno reso il processo pianificatorio farraginoso e lento. Innanzitutto, vanno sottolineati i ritardi istituzionali che hanno costretto l’approvazione definitiva del PRP a un decennio di ritardo e generato aspri conflitti istituzionali con l’amministrazione comunale guidata da Leoluca Orlando che aveva aperto un incomprensibile conflitto sulle competenze non riuscendo a vedere le opportunità di una governance estesa sull’area costiera e a cogliere l’occasione operativa di una sussidiarietà circolare nella rigenerazione del waterfront centrale di Palermo. Solo l’approccio diplomatico e manageriale del presidente Monti e poi la lungimiranza e l’approccio cooperativo dell’amministrazione comunale guidata da Roberto Lagalla hanno consentito, non solo di sbloccare l’inerzia dell’approvazione, ma di accelerare la realizzazione dei progetti urbani di dettaglio e di definire un accordo di collaborazione istituzionale per intervenire insieme (Autorità di Sistema Portuale e Comune di Palermo) in una porzione ampia e cruciale della città indipendente dai perimetri di competenza.

Un’altra criticità ha riguardato la necessità di liberare l’area portuale da una commistione e conflitto di funzioni ed edifici che, per la presenza di attività industriali o di stoccaggio, avevano portato a una progressiva chiusura e separazione dalla città, generando disvalore urbano di tutta l’area centrale della città che si affaccia sul mare. Nei fatti il mare era scomparso dall’orizzonte fisico e semantico di Palermo.

Naturally, the criticalities and barriers that made the planning process cumbersome and slow should not be overlooked. First, institutional delays forced the definitive approval of the PRP to arrive a decade late, amid harsh institutional conflicts with the municipal administration led by Leoluca Orlando, which opened an incomprehensible dispute over competencies, failing to recognize the opportunities of extended governance over the coastal area and to seize the operational occasion of circular subsidiarity in regenerating Palermo’s central waterfront. Only the diplomatic and managerial approach of President Monti—and later the foresight and cooperative stance of the municipal administration led by Roberto Lagalla—made it possible not only to break the inertia of approval, but also to accelerate the implementation of detailed urban projects and to define an institutional cooperation agreement to intervene jointly (Port System Authority and Municipality of Palermo) in a wide and crucial portion of the city, independent of formal jurisdictional boundaries.

Another criticality concerned the need to free the port area from a mixture and conflict of functions and buildings which—due to the presence of industrial or storage activities—had led to a progressive closure and separation from the city, generating urban devaluation across the entire central area facing the sea. In practice, the sea had disappeared from Palermo’s physical and semantic horizon.

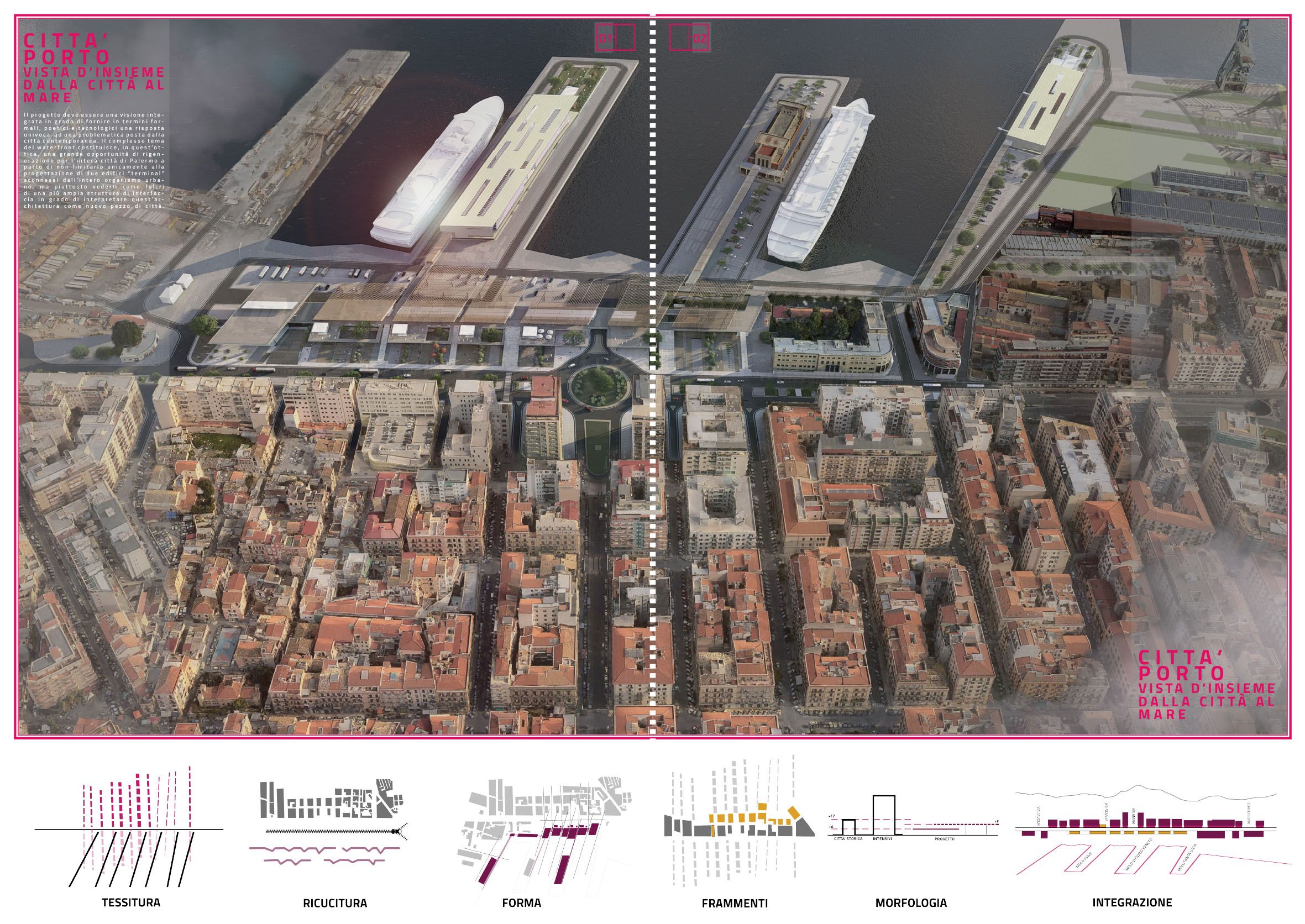

Interfaccia citta-porto. Il progetto per il terminal crociere/passeggeri di Palermo. (© Studio Valle).

City-port interface. The project for the Palermo cruise/passenger terminal. (© Studio Valle).

Dal conflitto alla simbiosi mutualistica tra porto e città

From Conflict to a Mutualistic Symbiosis Between Port and City

L’evoluzione della relazione porto-città a Palermo, negli ultimi venti anni, è passata da uno stato di separazione e marginalità a un modello di riconnessione strategica. Prima dell’avvio del PRP, l’area portuale era percepita come un luogo marginale, produttore di disvalore urbano, isolato dalla città. La svolta concettuale si colloca attorno al 2005, quando, grazie alla visione contemporanea e alle relazioni del sindaco Diego Cammarata, la Biennale di Venezia ha allestito a Palermo il suo primo padiglione off con la mostra internazionale “Città-Porto” (Bruttomesso, a cura di, 2006), contribuendo ad accendere la consapevolezza del potenziale dei waterfront come componenti urbane strategiche e quotidiane.

Il decennio successivo (2008-2018) è stato segnato dalla battaglia per l’approvazione del PRP, con il critico avvicendarsi delle amministrazioni Cammarata e Orlando, che, però, ha sancito l’innovazione di metodo e di merito: l’obiettivo di riportare Palermo sull’acqua non era solo funzionale, ma anzitutto strategico e di visione. Dal 2018 in poi, l’attuazione del piano portata avanti dal presidente Monti ha concretizzato la visione della città liquida, attraverso specifici Progetti Integrati di Trasformazione Portuale che hanno prodotto il definitivo riassetto di aree strategiche per lo sviluppo del traffico portuale e, contestualmente, hanno incrementato il rapporto tra la città e il porto, definendo le iconiche interfacce urbano-portuali.

Over the last twenty years, the evolution of the port–city relationship in Palermo has shifted from a condition of separation and marginality to a model of strategic reconnection. Before the launch of the PRP, the port area was perceived as a marginal place, producing urban disvalue and isolated from the city. The conceptual turning point can be located around 2005, when—thanks to the contemporary vision and relationships of Mayor Diego Cammarata—the Venice Biennale set up its first off-site pavilion in Palermo with the international exhibition “City–Port” (Bruttomesso, ed., 2006), helping to ignite awareness of the potential of waterfronts as strategic and everyday urban components.

The subsequent decade (2008–2018) was marked by the battle for the approval of the PRP, with the critical alternation of the Cammarata and Orlando administrations, which nonetheless consolidated innovation in both method and substance: the aim of bringing Palermo back to the water was not only functional, but above all strategic and visionary. From 2018 onward, implementation of the plan—advanced by President Monti through specific Integrated Port Transformation Projects—materialized the fluid city vision. These projects produced the definitive reconfiguration of strategic areas for the development of port traffic and, at the same time, strengthened the relationship between the city and the port by defining iconic urban–port interfaces.

Il progetto di riqualificazione del Porto di Sant’Erasmo, del Foro Italico e della passeggiata a mare adiacente. (© Studio Provenzano).

The redevelopment project for the Port of Sant’Erasmo, the Foro Italico, and the adjacent seafront promenade. (© Studio Provenzano).

Il primo progetto attuativo, l’emblema della visione, è stato la completa rigenerazione dell’ex molo trapezoidale da area industriale dismessa a un vibrante “quartiere d’acqua” denominato Palermo Marina Yachting e inaugurato nell’ottobre 2023 alla presenza del Presidente della Repubblica. Uno spazio che ibrida servizi alla nautica, musealizzazione archeologica del Castello a Mare, servizi culturali, commerciali e ricreativi di alta qualità. Questo ha creato una nuova centralità urbana, frequentata quotidianamente dai cittadini e dai turisti, a cui si aggiungeranno a breve un albergo di lusso e un centro congressi, completando lo spettro dello spazio urbano con funzioni ricettive/abitative e conviviali.

The first implementing project—the emblem of the vision—was the complete regeneration of the former trapezoidal pier, from a disused industrial area into a vibrant “water district” called Palermo Marina Yachting, inaugurated in October 2023 in the presence of the President of the Italian Republic. It is a space that hybridizes services for boating, the archaeological musealization of Castello a Mare, and high-quality cultural, commercial, and recreational services. This has created a new urban centrality, frequented daily by citizens and tourists, to which a luxury hotel and a congress center will soon be added, completing the spectrum of urban space with hospitality/residential and convivial functions.

Rendering Palermo Marina Yachting. (© Studio Provenzano).

Rendering Palermo Marina Yachting. (© Studio Provenzano).

Il secondo progetto attuativo, in corso di completamento, è l’area di interfaccia su Via Crispi, che prevede un dispositivo architettonico di spazi pubblici e giardini a varie altezze che ridisegnano la soglia tra città e porto, rendendola porosa. L’obiettivo è superare il confine, rendendo l’area permeabile e fruibile e permettendo alle funzioni urbane di riappropriarsi degli affacci sul mare. È, infatti, prevista la creazione di un parco urbano a quota stradale che sostituisce la recinzione con un’ampia zona aperta per attività commerciali e ricreative.

In sintesi, la relazione è evoluta da una netta separazione fisica e funzionale a una integrazione osmotica e strategica. Si è realizzata una vera e propria simbiosi mutualistica dove il porto è diventato parte integrante della vita urbana e generatore di valore, in linea con le tendenze internazionali che vedono i waterfront come luoghi dove gli interessi di amministratori, investitori, progettisti e cittadini si alleano in un’ottica proattiva e creativa.

The second implementing project, now nearing completion, is the interface area along Via Crispi, which envisages an architectural device of public spaces and gardens at various heights that redesign the threshold between city and port, making it porous. The objective is to overcome the boundary by rendering the area permeable and accessible, enabling urban functions to reclaim sea views. Indeed, the creation of an urban park at street level is planned, replacing the fence with a broad open zone for commercial and recreational activities.

In summary, the relationship has evolved from a clear physical and functional separation to an osmotic and strategic integration. A genuine mutualistic symbiosis has been achieved, in which the port has become an integral part of urban life and a generator of value, in line with international trends that view waterfronts as places where the interests of administrators, investors, designers, and citizens converge in a proactive and creative perspective.

Palermo Marina Yachting e il parco archeologico. (© Maurizio Carta).

Palermo Marina Yachting and the archaeological park. (© Maurizio Carta).

Le moderne strutture per yacht e imbarcazioni da diporto nel contesto suggestivo del Palermo Marina Yachting. (© Maurizio Carta).

Modern facilities for yachts and pleasure boats in the evocative setting of Palermo Marina Yachting. (© Maurizio Carta).

Il viaggio dell’eroe e le lezioni apprese

The Hero’s Journey and Lessons Learned

Palermo nella sua riconquista del mare ha percorso un viaggio di rinascita, di evoluzione, di fuga dall’eterno presente per raggiungere un nuovo futuro che è oggi il suo presente liquido. La immagino compiere, come i personaggi di un romanzo di formazione, il cosiddetto “viaggio dell’eroe”, la ben nota struttura narrativa teorizzata da Christopher Vogler nel saggio omonimo del 2007, in cui definisce un canone narrativo rintracciabile in gran parte delle storie epiche, dalla mitologia greca, passando per Shakespeare fino a giungere alle saghe dei libri, film e fumetti contemporanei. Anche Palermo compie questo viaggio, articolato in tappe che l’hanno condotta a vincere la battaglia con l’oblio del mare.

La prima tappa del viaggio di Palermo-eroina è il mondo ordinario in cui la città ha vissuto la sua esistenza dal dopoguerra fino ai primi anni del Duemila, con i suoi problemi, criticità, bisogni e aspirazioni, con il saccheggio dei suoi beni culturali e del paesaggio per costruire la brutta città moderna, con le sanguinarie guerre di mafia, con la corruzione endemica. La seconda tappa è la chiamata all’avventura, quando la città, dopo gli omicidi mafiosi di Giovanni Falcone e Paolo Borsellino, genera una voglia di riscatto morale e culturale e accetta la sfida della rigenerazione urbana a base culturale e creativa per stravolgere la condizione di declino in cui versava con le conseguenti condizione di crisi, impoverimento e abbandono. Come prescrive il canone narrativo, in un primo momento c’è il rifiuto della chiamata, lo scetticismo di una parte della comunità a imbarcarsi in un’avventura perigliosa e senza certezze, a muovere guerra a un nemico pernicioso esogeno ed endogeno contemporaneamente. La terza tappa è l’incontro con il mentore, in questo caso l’ingresso, negli anni Novanta, nella rete europea delle città Urban da cui apprendere buone pratiche, ma anche l’elezione di un nuovo e capace sindaco, Leoluca Orlando, che, grazie a visione e cultura, sprona la città ad affrontare la nuova sfida.

Da qui inizia il nuovo mondo straordinario di Palermo, fatto del superamento di soglie critiche, di assunzione di responsabilità, di prove di audacia, della ricerca di risorse e alleati e del riconoscimento di avversari (la mafia, ma non solo). In questa fase prendono forma più chiaramente le fazioni che si combatteranno d’ora in poi e che ancora si contendono il futuro della città: i conservatori e i riformisti, i primi che si accontentano della manutenzione dello status quo, i secondi che comprendono che deve cambiare tutto, a partire dagli spazi urbani e dai modi d’uso della città. Con un percorso di avvicinamento spesso periglioso, da qui in poi Palermo, eroina della rigenerazione, pianifica una strategia per affrontare le sfide. Nell’archetipo narrativo, di solito, il protagonista esce perdente dal primo combattimento, perché dopo una sconfitta possa rinascere più forte, e l’intoppo nel suo piano lo renderà più umano agli occhi dello spettatore/lettore, che si identificherà più facilmente. Anche Palermo, in alcuni casi, ha fallito le prime prove, per un problema imprevisto, per una crisi, per una congiura, per l’avvicendamento dei condottieri, ma questo, però, l’ha resa più forte per andare avanti, l’ha temprata e messa alla prova della sua resilienza.

Lungo la via del ritorno, dopo le battaglie perse e quelle vinte, la città dimostra di essere cambiata nei quasi quindici anni trascorsi, di aver saputo mettere a frutto l’avventura del cambiamento per affrontare il declino e la rinascita. Infine, la città, portando con sé l’eredità duratura della sfida affrontata, ha appreso numerose lezioni, e oggi, con l’amministrazione Lagalla, è tesa a riprendere il suo ruolo naturale nella scena urbana europea, tornando a confrontarsi nell’arena internazionale con importanti partenariati. È la ricompensa duratura per la sfida intrapresa, per la nuova vita che da quel momento in poi la caratterizzerà e che consentirà ai suoi abitanti di continuare a considerarla il loro ambiente di vita e di crescita e non un luogo da cui fuggire. Il primo progetto della rinascita è la riconquista del mare, a partire dal porto.

In its reconquest of the sea, Palermo has undertaken a journey of rebirth and evolution—a flight from an eternal present toward a new future that is now its liquid present. I imagine it undertaking, like the characters of a Bildungsroman, the so-called “hero’s journey,” the well-known narrative structure theorized by Christopher Vogler in the homonymous 2007 essay, in which he defines a narrative canon traceable in most epic stories, from Greek mythology, through Shakespeare, to contemporary book, film, and comic sagas. Palermo, too, performs this journey, articulated in stages that have led it to win the battle against the oblivion of the sea.

The first stage of Palermo-as-heroine is the ordinary world in which the city lived from the post-war period to the early 2000s, with its problems, criticalities, needs and aspirations: the plundering of its cultural assets and landscape to build the ugly modern city; the bloody mafia wars; endemic corruption. The second stage is the call to adventure, when—after the mafia murders of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino—the city generates a desire for moral and cultural redemption and accepts the challenge of culture- and creativity-based urban regeneration to overturn the condition of decline, crisis, impoverishment, and abandonment. As the narrative canon prescribes, there is initially a refusal of the call: the skepticism of part of the community about embarking on a perilous adventure without certainties, waging war against a pernicious enemy that is simultaneously exogenous and endogenous. The third stage is the meeting with the mentor: in this case, entry in the 1990s into the European Urban cities network, from which to learn good practices, as well as the election of a new and capable mayor, Leoluca Orlando, who—through vision and culture—spurs the city to face the new challenge.

From here begins Palermo’s new extraordinary world, made of overcoming critical thresholds, assuming responsibility, trials of audacity, searching for resources and allies, and recognizing adversaries (the mafia, but not only). In this phase, the factions that will fight from now on—and that still contend for the city’s future—take clearer form: conservatives and reformists; the former content with maintaining the status quo, the latter understanding that everything must change, starting with urban spaces and modes of use of the city. Through an often-perilous approach, from this point onward Palermo, heroine of regeneration, plans a strategy to address the challenges. In the narrative archetype, the protagonist usually loses the first combat so that, after defeat, they may be reborn stronger; the snag in the plan makes them more human in the eyes of the spectator/reader, who will identify more easily. Palermo, too, in some cases failed its first trials—because of an unforeseen problem, a crisis, a plot, a change of commanders—but this nonetheless made it stronger to move forward: it tempered it and tested its resilience.

Along the road back, after battles lost and won, the city proves that it has changed over the nearly fifteen years that have passed, having been able to capitalize on the adventure of change to face decline and rebirth. Finally, carrying the enduring legacy of the challenge faced, the city has learned numerous lessons and today—under the Lagalla administration—is poised to resume its natural role on the European urban stage, returning to compete in the international arena through significant partnerships. This is the enduring reward for the challenge undertaken, for the new life that from that moment onward will characterize it and allow its inhabitants to continue to consider it their environment of life and growth, rather than a place to flee. The first project of rebirth is the reconquest of the sea, beginning with the port.

Alcune immagini del Parco archeologico del Castello a Mare, “cuore storico” del più ampio complesso del Palermo Marina Yachting. (© Maurizio Carta).

Some images of the Castello a Mare Archaeological Park, the “historic heart” of the larger Palermo Marina Yachting complex. (© Maurizio Carta).

L’esperienza di Palermo, quindi, offre diverse lezioni significative per la pianificazione e la rigenerazione dei waterfront complessi. Innanzitutto, la necessità di una visione oltre la regolamentazione funzionale: il successo del progetto è radicato nella scelta di concepire il Piano Regolatore Portuale non come un mero strumento regolativo tradizionale, ma come un progetto strategico di scenario basato sul “paradigma della città liquida”. La pianificazione efficace del waterfront deve spiegare il perché del ritorno sull’acqua, superando la logica puramente funzionale.

La seconda lezione riguarda il valore delle interfacce porose: la chiave per la riconnessione risiede nella progettazione di “interfacce città-porto”. La distinzione in “porto liquido, permeabile e rigido” ha permesso di gestire contemporaneamente esigenze urbane (sviluppo, tempo libero, cultura) e portuali (efficienza, sicurezza, traffico merci/passeggeri). La permeabilità non è sinonimo di assenza di controllo, ma di osmosi funzionale e spaziale.

La terza lezione riguarda il ruolo del partenariato pubblico-privato e della leadership visionaria: la realizzazione dei progetti, come la rigenerazione del molo trapezoidale, è stata resa possibile grazie a finanziamenti rilevanti (30 milioni di euro dal Fondo Infrastrutture) e alla capacità di mobilitare risorse e leadership manageriali che hanno saputo tradurre la visione in interventi concreti. La rigenerazione del waterfront richiede necessariamente l’alleanza tra gli interessi di amministratori, investitori, promotori, progettisti e cittadini.

Infine, è stato cruciale l’impatto della qualità architettonica e urbana, con interventi come il Palermo Marina Yachting e l’interfaccia lungo via Crispi, che non solo offrono servizi, ma innalzano il rango dell’area portuale, riqualificano il tessuto edilizio circostante e attraggono nuove attività (culturali, creative, residenziali, co-working). La creazione di un nuovo spazio pubblico iconico è un indispensabile catalizzatore di rigenerazione urbana e sociale.

Palermo’s experience therefore offers several significant lessons for the planning and regeneration of complex waterfronts. First and foremost is the need for a “vision beyond functional regulation”: the project’s success is rooted in the choice to conceive the Port Master Plan not as a traditional regulatory tool, but as a strategic scenario-based project grounded in the “fluid city paradigm.” Effective waterfront planning must explain why returning to the water matters, overcoming a purely functional logic.

The second lesson concerns the value of “porous interfaces”: the key to reconnection lies in designing “city–port interfaces.” The distinction among “fluid, permeable and rigid port” made it possible to manage simultaneously urban needs (development, leisure, culture) and port needs (efficiency, safety, freight/passenger flows). Permeability is not synonymous with the absence of control, but with functional and spatial osmosis.

The third lesson concerns the role of “public–private partnership and visionary leadership”: the realization of projects such as the regeneration of the trapezoidal pier was made possible through significant funding (30 million euros from the Infrastructure Fund) and the ability to mobilize resources and managerial leadership capable of translating vision into concrete interventions. Waterfront regeneration necessarily requires an alliance among the interests of administrators, investors, promoters, designers, and citizens.

Finally, the impact of “architectural and urban quality” has been crucial, with interventions such as Palermo Marina Yachting and the interface along Via Crispi, which not only provide services but also raise the status of the port area, requalify the surrounding built fabric, and attract new activities (cultural, creative, residential, co-working). The creation of a new iconic public space is an indispensable catalyst for urban and social regeneration.

Futuri: il waterfront come “nuovo cardo”

Futures: The Waterfront as a “New Cardo”

Il piano di riappropriazione culturale, sociale ed economica del waterfront di Palermo non si è limitato all’area portuale, ma, dal 2022, con il nuovo Sindaco Roberto Lagalla e la mia responsabilità di assessore all’urbanistica e alla rigenerazione urbana, si è estesa a tutta la costa.

Palermo’s plan of cultural, social, and economic re-appropriation of its waterfront has not been limited to the port area; from 2022, with the new Mayor Roberto Lagalla and my responsibility as Councilor for Urban Planning and Urban Regeneration, it has extended to the entire coast.

Alcuni eventi culturali promossi lungo la costa: spettacolo teatrale sulle trasformazioni urbane di Palermo, regia e performance di Marina Mazzamuto (a sinistra); discoteca per una notte alla Stazione Marittima (a destra). (© Maurizio Carta).

Some cultural events promoted along the coast: a theatrical performance on the urban transformations of Palermo, directed and performed by Marina Mazzamuto (left); a one-night disco at the Maritime Station (right). (© Maurizio Carta).

Nella mia idea di Palermo del diverso presente come genesi del futuro, città composta da un arcipelago di luoghi rigenerati dove le persone trovino bellezza e lavoro, abitazione e benessere, creatività e inclusione, il fronte a mare è il nuovo “cardo” della città, l’asse nord-sud su cui si agganciano alcune delle funzioni più importanti e si dispiegano le principali aree risorsa (Carta, 2023). Un nuovo asse, diverso da quello tradizionale lungo via Oreto e via Libertà, che funge da dorsale tra la città e il mare, un asse cosmopolita che connette Palermo e il mondo. Un asse che trasforma la costa da frontiera a interfaccia porosa tra nuove funzioni della città liquida costantemente attraversate da diverse comunità che si miscelano in una danza di funzioni, in una sorellanza di aree e persone, per configurare lo spazio di una nuova specie urbana che torna in simbiosi con il mare.

In my idea of Palermo—where a different present is the genesis of the future, a city composed of an archipelago of regenerated places where people can find beauty and work, housing and well-being, creativity and inclusion—the seafront is the city’s new “cardo,” the north–south axis to which some of the most important functions are anchored and along which the main resource areas unfold (Carta, 2023). This is a new axis, different from the traditional one along Via Oreto and Via Libertà, which functions as a backbone between city and sea: a cosmopolitan axis connecting Palermo and the world. An axis that transforms the coast from frontier into a porous interface among new functions of the fluid city, constantly traversed by different communities that mix in a dance of functions, in a sisterhood of areas and people, configuring the space of a new urban species returning to symbiosis with the sea.

La foce del fiume Oreto e l’Ecomuseo Mare Memoria Viva. (© Maurizio Carta).

The mouth of the Oreto River and the Mare Memoria Viva Ecomuseum. (© Maurizio Carta).

Lungo questo nuova dorsale formata da terra e mare si dispiegano alcune tra le più importanti criticità, opportunità e aree in trasformazione di Palermo. Da nord a sud, le borgate marinare e balneari di Sferracavallo e Mondello da riqualificare, la costa dell’Addaura e il Monte Pellegrino con la grande riserva naturale della Favorita, le borgate di Vergine Maria, Arenella e Acquasanta con i loro porti in diversi gradi di efficienza e le comunità retrostanti rese fragili, le grandi aree produttive dismesse della ex Chimica Arenella, della ex Manifattura Tabacchi, dei vecchi Bagni Pandolfo e dei magazzini dismessi della Tirrenia.

E poi troviamo il porto in portentoso sviluppo e trasformazione, con l’area passeggeri, merci e crocieristica in tumultuosa crescita, la futura interfaccia città-porto con le sue terrazze, giardini e negozi, la nuova Stazione Marittima che si fa anche discoteca, ristorante, terrazza, luogo di sfilate di moda ed eventi, a cui segue il quartiere d’acqua al Molo Trapezoidale, che ho descritto prima. Più a sud, dopo il fiume Oreto, troviamo la complessa, martoriata, vitale, fragile –ma anche manifatturiera, educativa e artistica– Costa Sud, per la quale il Comune di Palermo ha progettato interventi di bonifica e recupero per quasi 60 milioni di euro finanziati da risorse extra-comunali. Un susseguirsi di quartieri (Romagnolo, Settecannoli, Sperone, Bandita, Roccella), di paesaggi costieri ed ex lidi balneari, di arenili naturali e artificiali, di case in linea e fabbriche di mattoni, fino al parco “Libero Grassi” ad Acqua dei Corsari, futuro emblema di un riscatto urbano e sociale dell’area e dell’intera città, grazie a un finanziamento regionale di circa 11 milioni di euro per la sua bonifica.

Along this new backbone of land and sea unfold some of Palermo’s most important criticalities, opportunities, and areas in transformation. From north to south: the maritime and seaside hamlets of Sferracavallo and Mondello to be redeveloped; the Addaura coast and Monte Pellegrino with the large natural reserve of the Favorita; the hamlets of Vergine Maria, Arenella and Acquasanta with their ports at various levels of efficiency and the fragile communities behind them; the large disused productive areas of the former Chimica Arenella, the former Manifattura Tabacchi, the old Bagni Pandolfo, and the disused Tirrenia warehouses.

Then we find the port, in powerful development and transformation, with the passenger, freight and cruise areas in tumultuous growth; the future city–port interface with its terraces, gardens and shops; the new Maritime Station that also becomes a nightclub, restaurant, terrace, venue for fashion shows and events, followed by the water district at the trapezoidal pier described above. Further south, beyond the Oreto river, lies the complex, battered, vital, fragile—but also manufacturing, educational and artistic—South Coast, for which the Municipality of Palermo has designed remediation and recovery interventions for almost 60 million euros financed by extra-municipal resources: a succession of neighborhoods (Romagnolo, Settecannoli, Sperone, Bandita, Roccella), coastal landscapes and former bathing establishments, natural and artificial beaches, linear housing blocks and brick factories, up to the “Libero Grassi” park at Acqua dei Corsari, a future emblem of an urban and social redemption of the area and of the whole city, thanks to a regional funding of about 11 million euros for its remediation.

Il murale nel quartiere Sperone dedicato a Fratel Biagio Conte (1963-2023), missionario laico di Palermo noto come “l’angelo dei poveri”. (© Maurizio Carta).

The mural in the Sperone district dedicated to Brother Biagio Conte (1963-2023), a lay missionary from Palermo known as “the angel of the poor”. (© Maurizio Carta).

La Fabbrica di Mattoni lungo la Costa sud. (© Maurizio Carta).

The Brick Factory along the South Coast. (© Maurizio Carta).

È un asse di enormi potenzialità e risorse, composto da luoghi fragili e potenti allo stesso tempo, che pretendono un progetto complessivo che ricucia le relazioni tra città e mare, che generi e rigeneri un nuovo fronte a mare, che sia propulsore di un progetto di città. Una dorsale che connette organi urbani, una spina su cui si agganciano porzioni di futuro per le quali serve una visione e una progettazione comuni, come una linea di uno spartito su cui si appoggiano con sapienza e armonia le note della partitura urbana che faccia risuonare la musica della città futura. Per rendere concreta questa visione integrata tra città e mare è stato siglato nel 2023 un apposito accordo tra il Comune di Palermo e l’Autorità di Sistema Portuale per la co-progettazione e la gestione integrata di tutte le aree di interfaccia, che, recentemente, è stato ulteriormente esteso dal commissario straordinario dell’AdSP, Annalisa Tardino, per poter utilizzare risorse regionali al completamento delle porzioni urbane dell’area di interfaccia città-porto e alla connessione aerea tra il porto e la città, sancendo la definitiva simbiosi tra le due parti, eliminando qualsiasi soglia.

It is an axis of enormous potentialities and resources, composed of places at once fragile and powerful, demanding an overarching project capable of re-stitching relations between city and sea, generating and regenerating a new seafront, and acting as the driver of a city project. A backbone that connects urban organs, a spine onto which portions of the future are attached, for which a shared vision and design are required—like a staff line on which the notes of the urban score rest with knowledge and harmony, so that the music of the future city can resonate. To make this integrated vision between city and sea concrete, in 2023 a specific agreement was signed between the Municipality of Palermo and the Port System Authority for the co-design and integrated management of all interface areas; more recently, it was further extended by the Extraordinary Commissioner of the AdSP, Annalisa Tardino, to enable the use of regional resources to complete the urban portions of the city–port interface area and the aerial connection between the port and the city, sanctioning the definitive symbiosis between the two parts and eliminating any threshold.

Il Parco Libero Grassi lungo la Costa Sud, futuro emblema di un riscatto urbano e sociale dell’area. (© Maurizio Carta).

The Libero Grassi Park along the South Coast, a future emblem of the area’s urban and social revitalization. (© Maurizio Carta).

L’accordo è stato un primo passo per la riconfigurazione complessiva della costa. La fase successiva sarà redigere il nuovo Piano Urbanistico Generale (in corso di elaborazione) e approvare il Piano d’Uso del Demanio Marittimo (elaborato a fine 2025) che comprenda una fascia di città che, a partire dalla linea di costa, intercetti tutte le grandi aree di trasformazione sia longitudinalmente che trasversalmente (entrando dentro il tessuto urbano per comprendere l’area fieristica e la ex stazione ferroviaria Sampolo, l’ex macello e l’ex gasometro, i quartieri di Borgo Vecchio e Brancaccio, solo per fare qualche esempio). Serve oggi un disegno urbanistico complessivo che dia organicità alla rigenerazione e sviluppo delle aree in transizione, conformando anche lo spazio residenziale, definendo l’adeguata mobilità, configurando in maniera complementare lo spazio pubblico e definendo i criteri di salvaguardia dei valori culturali e paesaggistici coinvolti.

The agreement was a first step toward an overall reconfiguration of the coast. The subsequent phase will be to draft the new General Urban Plan (currently under development) and approve the Coastal State Property Use Plan (completed at the end of 2025), which will include a band of the city that, starting from the coastline, intercepts all major transformation areas both longitudinally and transversally (penetrating into the urban fabric to include the fairground area and the former Sampolo railway station, the former slaughterhouse and former gasometer, the neighborhoods of Borgo Vecchio and Brancaccio, just to mention a few examples). What is needed today is a comprehensive urban design that gives organic coherence to regeneration and development in areas in transition, shaping residential space as well, defining adequate mobility, configuring public space in a complementary manner, and establishing criteria for safeguarding the cultural and landscape values involved.

Conclusioni

Conclusions

La pianificazione urbanistica integrata con la rigenerazione urbana forniranno stimolo all’innovazione spaziale, sociale, culturale ed economica, costituiranno quadro di coerenza ai fondi extra-comunali necessari, daranno certezza del diritto ai cospicui investimenti da attrarre, e, soprattutto, forniranno una identità complessiva alla rigenerazione lungo il cardo costiero, evitando la frammentazione degli interventi di recupero che ne indebolirebbe l’impatto e allontanerebbe nel tempo il ritorno dell’investimento dei partner e investitori privati.

Il waterfront di Palermo, quindi, è il luogo dove il futuro accadrà, come mi piace definirlo: una porzione vibrante della città che funge da innesco e da propulsore per il complessivo progetto di sviluppo della città del futuro prossimo venturo, a misura delle nuove generazioni. Uno sviluppo fondato sul “paradigma della città liquida”, che ha guidato la pianificazione non solo regolativa ma strategica, non solo prescrittiva ma generativa, non solo spaziale ma civica. Il caso Palermo, quindi, non si limita a dimostrare l’importanza cruciale del waterfront come cerniera tra i flussi globali e la rigenerazione urbana creativa, ma ha l’ambizione di proporsi come nuovo protocollo e canone di una necessaria “urbanogenesi” (Carta, 2025), una rigenerazione che produca nuova urbanità e non solo un aumento dei valori economico-finanziari.

Nel 2005 lo scrittore David Foster Wallace tenne ai giovani laureati del Kenyon College in Ohio una lezione esordendo così: «Ci sono due giovani pesci che nuotano uno vicino all’altro e incontrano un pesce più anziano che, nuotando in direzione opposta, fa loro un cenno di saluto e poi dice “Buongiorno ragazzi. Com’è l’acqua?” I due giovani pesci continuano a nuotare per un po’, e poi uno dei due guarda l’altro e gli chiede “ma cosa diavolo è l’acqua?””. Io immagino che il processo/progetto per la rigenerazione del waterfornt di Palermo possa rispondere alle nuove generazioni che abiteranno la città: questa è l’acqua.

Integrated urban planning coupled with urban regeneration will stimulate spatial, social, cultural and economic innovation; it will provide a coherent framework for the necessary extra-municipal funds; it will ensure legal certainty for the substantial investments to be attracted; and, above all, it will provide an overall identity to regeneration along the coastal cardo, avoiding the fragmentation of recovery interventions that would weaken their impact and postpone the return on investment for private partners and investors.

Palermo’s waterfront is therefore the place where the future will happen—as I like to define it: a vibrant portion of the city that acts as a trigger and driver for the overall development project of the city of the near future, tailored to the new generations. A development founded on the “fluid city paradigm,” which has guided planning that is not only regulatory but strategic, not only prescriptive but generative, not only spatial but civic. The Palermo case thus not only demonstrates the crucial importance of the waterfront as a hinge between global flows and creative urban regeneration, but also aspires to propose itself as a new protocol and canon of a necessary “urbanogenesis” (Carta, 2025): a regeneration that produces new urbanity and not merely an increase in economic–financial values.

In 2005, writer David Foster Wallace gave a lecture to young graduates of Kenyon College in Ohio, beginning with this: «There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swims on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?” I imagine that the process/project for the regeneration of Palermo’s waterfront can respond to the new generations who will inhabit the city: this is water.

IMMAGINE INIZIALE | Palermo Marina Yachting, area portuale riqualificata situata sul Molo Trapezoidale del porto di Palermo. (© Maurizio Carta).

HEAD IMAGE | Palermo Marina Yachting, a redeveloped port area located on the Trapezoidal Pier of the port of Palermo. (© Maurizio Carta).

╝

RIFERIMENTI

REFERENCES

Bruttomesso R., a cura di (2006), Città-Porto. Palermo. Catalogo della 10ª Mostra internazionale di architettura, Marsilio, Venezia.

Carta M. (2018), “Progettare la città liquida. Il nuovo Piano Regolatore Portuale di Palermo”, in Portus, n. 36.

Carta M. (2023), Palermo, un’idea di cui è giunto il tempo, Marsilio, Venezia.

Carta M. (2025), Sette lezioni di rigenerazione urbana, LetteraVentidue, Siracusa.

Carta M., Ronsivalle D., eds. (2016), The Fluid City Paradigm. Waterfront Regeneration as an Urban Renewal Strategy, Springer, Cham.

Carta M., La Greca P., Ronsivalle D., Lino B. (2025), Planning Complex Waterfront Interfaces. Reshaping Port City Regeneration for Sustainable Urban Futures, Springer, Cham.

Giovinazzi O., Moretti M. (2010), “Port Cities and Urban Waterfront: Transformations and Opportunities”, in Tema. Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, 2.

Hein C. (2014) “Port cities and urban wealth: between global networks and local transformations”, in International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 13(2-4), pp.339-361.