╔

Cruceros en Costa Rica

En Costa Rica puede hablarse de industria de cruceros a partir del año 1988. Antes de esa fecha no se registran datos en JAPDEVA, la Autoridad Portuaria del Caribe. De modo que, cualquier arribo previo ha sido considerado como caso fortuito, por no existir una ruta, ni la articulación de servicios a nivel local.

Los primeros cruceros que llegaron al país atracaron en Limón, en el conocido Muelle Alemán, compartiendo el espacio portuario con buques de contenedores, de carga paletizada, Ro-Ro y carga general. De esta forma, Costa Rica se integró a la industria globalizada de los cruceros, dando sus primeros pasos en un contexto mundial de cambios acelerados; cuando se estaban conformando las macroempresas, se construían buques de mayor tamaño y se abrían ofertas atractivas, para explotar el potencial de este nuevo concepto de turismo.

El Caribe era el destino más popular y, la industria de cruceros estaba conformada por 13 líneas navieras agrupadas en la FCCA (Florida Caribbean Cruise Association); entre ellas habían tres grandes compañías: Carnival Corporation, Royal Caribbean Cruises (RCC) y P&O Princes Cruises.

Estas líneas navieras habían segmentado la región en cuatro áreas: Las Bahamas, Oriente, Occidente y el Sur Caribeño. México en ese momento empezó a desarrollar los puertos de la Península de Yucatán y de la isla Cozumel, facilitando el establecimiento de itinerarios con puertos vecinos al sur, entre ellos: Puerto Quetzal en Guatemala, Belice, San Juan del Sur en Nicaragua, Limón y Puntarenas en Costa Rica, Colón 2000 y Puerto Amador en Panamá.

Entre tanto, los puertos del Caribe se esforzaban por mejorar sus instalaciones y promocionarse para atraer este tráfico, esta dinámica contribuyó a mejorar la relación entre la ciudad y el puerto.

Para el año 2004, los expertos recomendaban a los países de la región, convertir sus puertos en terminales para mega cruceros. Sin embargo, este tipo de inversiones requería de un análisis cuidadoso del mercado, porque el turismo de cruceros depende de factores que suelen presentar un alto grado de volatilidad: las condiciones económicas en los países de origen, la continuidad del crecimiento de los viajes internacionales, los precios de los combustibles, las amenazas relacionadas con desastres naturales, las condiciones geopolíticas y hasta el tipo de cambio del dólar estadounidense (la correcta situación de estas variables contribuye, pero no determina el marco de posibilidades, que tiene un puerto para ser elegido o no como puerto de escala). Además, otros factores juegan en esta dinámica como la infraestructura o, los aspectos comerciales, logísticos y sociales; pero el éxito depende en buena parte de las capacidades de inversión y planificación que tengan las administraciones de Estado, de los inversionistas privados y de actores locales.

La infraestructura portuaria siempre ha sido un talón de Aquiles para Costa Rica. Esto puede constatarse en los índices globales de competitividad, que cada año publica el Foro Económico Mundial. Por ello, desde el inicio de la actividad de cruceros se debió considerar el tamaño de los buques, para prever limitaciones de eslora y calado. Así mismo, debió considerase la velocidad de los buques, porque de ésta dependen itinerarios, recorrido y el número de escalas posibles.

Los factores comerciales se han enfocado en el tipo de clientes, los precios, la competencia, la organización existente en la región, la rentabilidad y otros.

Los factores logísticos agrupan al puerto y su entorno, analizando temas de operación portuaria, como la disponibilidad de atraque, canales de acceso al muelle, fondeaderos, facilidades para el embarque y desembarque de los pasajeros. También derivan hacia elementos de itinerario, como las condiciones del transporte terrestre, y hasta el avituallamiento del buque.

In Costa Rica, we can speak of the cruise industry starting in 1988. Before that date, no data was recorded in JAPDEVA, the Caribbean Port Authority. Therefore, any prior arrival has been considered a fortuitous event, as there was no route, nor the services links at the local level.

The first cruise ships that arrived in the country docked in Limón, at the well-known German Dock, sharing the port space with container ships, palletized cargo, Ro-Ro and general cargo. In this way, Costa Rica joined the globalized cruise industry, taking its first steps in a world context of accelerated changes; when the macro-companies were being formed, larger ships were being built and attractive offers were being made to exploit the potential of this new concept of tourism.

The Caribbean was the most popular destiny, and the cruise industry was made up of 13 shipping lines grouped in the FCCA (Florida Caribbean Cruise Association); among them were three large companies: Carnival Corporation, Royal Caribbean Cruises (RCC), and P&O Princes Cruises.

These shipping lines had segmented the region into four areas: The Bahamas, the East, the West, and the South Caribbean. Mexico at that time began to develop the ports of the Yucatan Peninsula and Cozumel Island, making easier the establishment of itineraries with neighboring ports to the south, among them: Puerto Quetzal in Guatemala, Belize, San Juan del Sur in Nicaragua, Limón and Puntarenas in Costa Rica, Colón 2000 and Puerto Amador in Panama.

Meanwhile, the Caribbean ports were striving to improve their facilities and promote themselves to attract this traffic, this dynamic contributed to improving the relationship between the city and the port.

By 2004, experts recommended that the countries of the region convert their ports into terminals for mega cruise ships. However, this type of investment required a careful analysis of the market, because cruise tourism depends on factors that tend to present a high degree of volatility: economic conditions in the origin countries, the continued growth of international travel, fuel prices, threats related to natural disasters, geopolitical conditions and even the US dollar exchange rate (the correct situation of these variables contributes, but does not determine the framework of possibilities, that a port has to be chosen or not as a port of call). In addition, other factors play in this dynamic such as infrastructure or commercial, logistic and social aspects; but success largely depends on the investment and planning capacities of state administrations, private investors and local actors.

Port infrastructure has always been an Achilles’ heel for Costa Rica. This can be seen in the global competitiveness index, which are published each year by the World Economic Forum. For this reason, from the beginning of the cruise activity, the size of the ships had to be considered, to anticipate length and draft limitations. Likewise, the speed of the ships should have been considered, because itineraries, number of possible routes and stopovers depend on it.

The commercial factors have focused on the type of clients, prices, competition, the existing organization in the region, profits and others.

Logistical factors group the port and its surroundings, analyzing port operation issues, such as the availability of berths, access channels to the dock, anchorages, facilities for embarking and disembarking passengers. They also refer to elements of the itinerary, such as the conditions of land transport, and even the provisioning of the ship.

El muelle de cruceros en Puerto Limón. (Fuente: https://www.cmc-shipagents.com/puertos/costa-rica-2/limon/).

The cruise ship dock in Port Limon. (Source: https://www.cmc-shipagents.com/puertos/costa-rica-2/limon/).

El factor social es más amplio y complejo, pero pueden mencionarse al menos dos dimensiones: la que analiza al consumidor, es decir al crucerista y, la que analiza el entorno social que recibe al buque. En la primera, se observa el comportamiento, hábitos y costumbres de los posibles clientes para detectar sus preferencias. En este sentido el Instituto Costarricense de Turismo – ICT llegó a estimar que “los turistas europeos prefieren numerosas escalas y actividades en tierra, como excursiones y visitas culturales,…, mientras que el estadounidense promedio prefiere mayor permanencia en el buque y disfrutar sus servicios.” En función de tales estimaciones se definió un inventario de recursos cercanos al puerto, como gastronomía, atractivos de patrimonio cultural, playas, parques o reservas naturales, sitios de compras y otras atracciones comerciales.

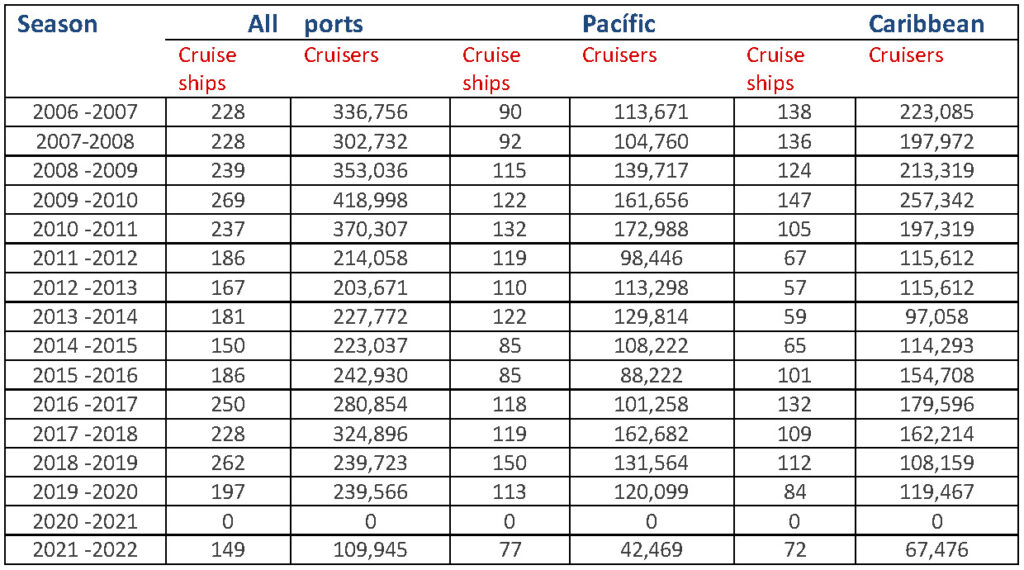

El periodo de mayor actividad en la industria de cruceros inicia en el año 2006, pero es muy oportuno señalar que en los años 2016-2017 y 2018 se realizaron importantes esfuerzos de coordinación entre autoridades portuarias y el Ministerio de Turismo, para potenciar su desarrollo.

The social factor is broader and more complex, but at least two dimensions can be mentioned: the one that analyzes the consumer, that is, the cruise passenger, and the one that analyzes the social environment that receives the ship. In the first, the behavior, habits and customs of potential customers are observed to detect their preferences. In this sense, the Costa Rican Institute of Tourism – ICT came to estimate that “European tourists prefer numerous stopovers and activities on land, such as excursions and cultural visits,…, while the average American prefers a longer stay on the ship and enjoy its services”. Based on these estimates, an inventory of resources near the port was defined, such as gastronomy, cultural heritage attractions, beaches, parks or nature reserves, shopping sites and other commercial attractions.

The period of greatest activity in the cruise industry began in 2006, but it is very timely to point out that in the years 2016-2017 and 2018 significant coordination efforts were made between port authorities and the Ministry of Tourism, to enhance their development.

Llegada de cruceros y cruceristas a Costa Rica. (Fuente: Instituto Costarricense de Turismo ITC con información de INCOP, JAPDEVA y las oficinas regionales de la Dirección General de Migración y Extranjería).

Arrival of cruise ships and cruise passengers to Costa Rica. (Source: Costa Rican Institute of ICT Tourism with information from INCOP, JAPDEVA and the regional offices of the General Directorate of Migration and Immigration).

Los impactos del COVID-19

The impacts of COVID-19

La pandemia de COVID-19 fue un desastre en términos humanitarios, que además afectó de gravedad al turismo y, en particular, a la industria de cruceros.

En Costa Rica fue muy sensible el impacto económico, porque la actividad turística es, desde hace décadas, un motor de la economía. Tiene un significativo aporte a las exportaciones, al PIB y al empleo, siendo una actividad fundamental para el desarrollo socioeconómico de las regiones costeras.

Con la reapertura de las fronteras y la flexibilización de las restricciones a la movilidad, se empezó a recuperar la llegada de turistas internacionales.

Las ciudades de Limón y Puntarenas, después de dieciocho meses de no recibir cruceros, se reactivaron con rigurosos protocolos de bioseguridad – a bordo y en tierra- para garantizar experiencias saludables y seguras.

El resultado de la experiencia “post-pandemia” muestra que las ciudades portuarias y las empresas de cruceros son más resilientes; más capaces de comprender y responder a los cambios de comportamiento de la demanda y a la percepción de los viajeros respecto de la seguridad.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a disaster in humanitarian terms, which also seriously affected tourism and, particularly, the cruise industry.

In Costa Rica, the economic impact was very sensitive, because tourism activity has been, for decades, an engine of the economy. It has a significant contribution to exports, to GDP and employment, being a fundamental activity for the socioeconomic development of the coastal regions.

With the borders reopening and the relaxation of mobility restrictions, the arrival of international tourists began to recover.

Limón and Puntarenas cities, after eighteen months of not receiving cruise ships, were reactivated with rigorous biosafety protocols – on board and on land – to guarantee healthy and safe experiences.

The result of the “post-pandemic” experience shows that port cities and cruise companies are more resilient; much better able to understand and respond to changes in demand behavior and traveler perceptions of safety.

Los retos actuales

Current challenges

La ausencia de una mirada a largo plazo podría ser el principal reto que tiene Costa Rica en el sector portuario y, particularmente, en la industria de cruceros. Pese a que existen instituciones y organizaciones dinámicas y propositivas, parece que no han logrado articular esfuerzos, para avanzar con una mirada compartida.

Las autoridades portuarias tienen una ventaja significativa en imponer un discurso; una narrativa cuya fuerza radica en los recursos económicos con los que cuentan y en la normativa que los respalda e impulsa a hacer inversiones de obra pública y concesionar terminales portuarias. Por lo tanto, son los llamados a actuar, para recuperar y desarrollar el subsector turístico de cruceros.

En la Costa del Pacífico, la Autoridad Portuaria – INCOP cuenta con la Ley N°8461 (conocida como Ley Caldera), la Ley N°7782 sobre optimización de activos de infraestructura y, un fideicomiso bancario de casi 8 millones de dólares. Además, disponen de una iniciativa privada de una empresa española para asumir la operación de la terminal.

En la costa del Caribe, la Autoridad Portuaria incluye en su ley constitutiva la tarea de procurar el desarrollo socioeconómico de la vertiente atlántica, y cuenta con un fideicomiso de más de 55 millones de dólares, pero hasta ahora no tienen una estrategia, ni plan de inversión en bienes de capital. Estos fideicomisos bancarios se nutren del canon que pagan las terminales concesionadas.

El compromiso social de la Autoridades portuarias tiene una larga historia. Ambas han hecho inversiones importantes para mejorar la vida de los habitantes y el confort de los turistas. Sin embargo, muchas de estas obras han quedado dispersas o representan esfuerzos diluidos por obsolescencia o pérdida de vigencia. Por lo general, fueron hechas sin responder a una estrategia o a un plan de inversiones sustentado en criterios técnicos y científicos.

La industria de cruceros en Limón y en Puntarenas tiene el reto de actualizar tanto el frente marítimo como el hinterland turístico. Por ejemplo, las terminales de cruceros deben ser pensadas como hitos arquitectónicos que formen parte del frente marítimo y le den identidad al Skyline de la ciudad.

The absence of a long-term view could be the main challenge that Costa Rica faces in the port sector and, particularly, in the cruise industry. Even though there are dynamic and proactive institutions and organizations, it seems that they have not been able to coordinate efforts to advance with a shared vision.

Port authorities have a meaninful advantage in imposing a discourse; a narrative whose strength lies in the economic resources they have and in the regulations that support and encourage them to invest in public works and concession port terminals. Therefore, they are called to act, to recover and develop the cruise tourism subsector.

On the Pacific Coast, the Port Authority – INCOP has Law No. 8461 (known as the Caldera Law), Law No. 7782 on optimization of infrastructure assets and a bank trust of almost 8 million dollars. In addition, they have a private initiative from a Spanish company to take over the operation of the terminal.

On the Caribbean coast, the Port Authority includes in its constitutive law the task of ensuring the socioeconomic development of the Atlantic slope and has a trust fund of more than 55 million dollars, but until now they do not have a strategy or plan of investment in capital goods. These bank trusts are nourished by the fee paid by the concession terminals.

The social commitment of the Port Authorities has a long history. Both have made significant investments to improve inhabitants lives and tourist’s comfort. However, many of these works have been dispersed or represent diluted efforts due to obsolescence or loss of validity. In general, they were made without responding to an investment strategy or plan based on technical and scientific criteria.

The cruise industry in Limón and Puntarenas has the challenge of updating both the maritime front and the tourist hinterland. For example, cruise terminals should be thought of as architectural landmarks that form part of the sea front and give identity to the skyline of the city.

La terminal de cruceros ubicada en la Terminal Portuaria Hernán Garrón Salazar. (Fuente: https://www.mundomaritimo.cl/noticias/puerto-de-limon-costa-rica-japeva-selecciono-a-seis-oferentes-para-segunda-etapa-de-evaluacion-de-terminal-de-cruceros/).

The cruise terminal located in the Hernán Garrón Salazar Port Terminal. (Source: https://www.mundomaritimo.cl/noticias/puerto-de-limon-costa-rica-japeva-selecciono-a-seis-oferentes-para-segunda-etapa-de-evaluacion-de-terminal-de-cruceros).

El hinterland turístico en los puertos de escala, como lo son Limón y Puntarenas, se define empíricamente como el área que alcanzan las excursiones ofrecidas a los pasajeros. Este Hinterland es un componente del itinerario, porque delimita las experiencias y actividades posibles de ser realizadas por los cruceristas. En esta perspectiva, se deben planificar las inversiones para fomentar un mayor vínculo regional y potenciar el efecto multiplicador de la industria de cruceros en otras áreas económicas y sociales, un poco alejadas de la ciudad portuaria.

Las autoridades portuarias, los gobiernos locales y el Ministerio de Turismo deben considerar dos aspectos.

El primero, que el camino de la sostenibilidad en las zonas costeras requiere de potenciar la industria de cruceros, con una adecuada planificación de la ciudad y el hinterland turístico, porque esto favorece los itinerarios y evita sobrepasar la capacidad de carga de los destinos. Entonces vale preguntarse: ¿qué tipo de puerto queremos? ¿Un puerto Gateway en donde los principales lugares de interés turístico se encuentran fuera de la ciudad portuaria? ¿Un puerto Balanced que se caracteriza por distribuir a los cruceristas de forma equilibrada, porque tanto la ciudad portuaria como su hinterland tienen dotaciones similares de atracciones turísticas? Esto es importante de definir, porque al final la ciudad portuaria y el hinterland turístico deben funcionar como un conjunto sólido de facilidades, para conseguir el éxito del itinerario.

El segundo aspecto, es percatarse de que la mayor parte de las divisas turísticas que reciben las ciudades portuarias llegan en cruceros, pero la ciudad portuaria continúa bajo un diseño para recibir a los turistas por tierra.

Dicho lo anterior, a las instancias de toma de decisiones les conviene trabajar de forma articulada bajo el modelo de gobernanza que mejor les funcione, teniendo presente que las universidades públicas pueden jugar un rol muy importante, por el tipo de trabajo que realizan. En particular el PROCIP de la UNED, único especialista en Costa Rica en las relaciones puerto-ciudad.

The tourist hinterland in the ports of call, such as Limón and Puntarenas, is empirically defined as the area reached by the excursions offered to passengers. This hinterland is a component of the itinerary, because it delimits the possible experiences and activities to be carried out by cruise passengers. In this perspective, investments must be planned to promote a greater regional link and enhance the multiplier effect of the cruise industry in other economic and social areas, a little far from the port city.

Port authorities, local governments and the Ministry of Tourism must consider two aspects.

The first is that the path to sustainability in coastal areas requires strengthening the cruise industry, with proper planning of the city and the tourist hinterland, because this favors itineraries and avoids exceeding the carrying capacity of destinations. So, it is worth asking: what kind of port do we want? A gateway port where the main tourist attractions are outside the port city? A balanced port that is characterized by distributing cruise passengers in a balanced way, because both the port city and its hinterland have similar endowments of tourist attractions? This is important to define, because in the end the port city and the tourist hinterland must function as a solid set of facilities to achieve the success of the itinerary.

The second aspect is to realize that most of the tourist currency received by port cities arrives on cruise ships, but the port city continues under a design to receive tourists by land.

That said, it is convenient for decision-making bodies to work in an articulated manner under the governance model that works best for them, bearing in mind that public universities can play a very important role, due to the type of work they do; in particular, the PROCIP of UNED, the only specialist structure in Costa Rica in port-city relationships.

IMAGEN INICIAL | La llegada de cruceros a Puerto Limón y Costa Rica, una actividad socioeconómica de gran relevancia. (Fuente: https://www.japdeva.go.cr/administracion_portuaria/Cruceros.html).

HEAD IMAGE | The arrival of cruise ships in Puerto Limón and Costa Rica, a highly relevant socioeconomic activity. (Source: www.japdeva.go.cr/administracion_portuaria/Cruceros.html).