╔

Del enclave portuario al territorio compartido: Desafíos de integración puerto-ciudad en Valparaíso

Valparaíso: Un caso singular de ciudad-puerto en la encrucijada chilena

Valparaíso: A unique case of a port-city at the Chilean crossroads

Chile atraviesa una transformación histórica hacia la descarbonización económica, donde el hidrógeno verde y las energías renovables emergen como catalizadores del cambio. Tres territorios estratégicos lideran esta transición: la Región de Antofagasta, con Mejillones como epicentro industrial; la macrozona central —conformada por las regiones Metropolitana, Valparaíso y O’Higgins—, que concentra los principales centros de consumo y sectores productivos; y la Región de Magallanes, con su excepcional potencial eólico y acceso privilegiado a rutas marítimas globales. En este escenario, Valparaíso y su sistema urbano metropolitano adquieren renovada relevancia estratégica como nodo logístico fundamental. Las ciudades puerto enfrentan desafíos críticos —obsolescencia de infraestructuras, congestión operativa y presiones climáticas—, pero simultáneamente encuentran oportunidades en la economía azul, posicionándose como nodos del comercio global que deben equilibrar crecimiento económico con sostenibilidad territorial.

La comprensión del rol de Valparaíso en esta transición requiere situarlo en su contexto histórico y territorial. La ciudad se erigió como la “Joya del Pacífico” desde el siglo XIX hasta principios del XX, funcionando como principal centro de intercambio comercial y financiero de la costa occidental sudamericana. Su declive comenzó con el terremoto de 1906 y, crucialmente, con la apertura del Canal de Panamá en 1914, que reorientó las rutas marítimas internacionales. El proceso de regionalización implementado durante el régimen militar configuró decisivamente una nueva relación entre Santiago y Valparaíso: la Región Metropolitana fue delimitada sin borde costero precisamente para potenciar el desarrollo económico regional hacia el oeste. Esta decisión, junto con la posterior instalación del Congreso Nacional en Valparaíso en 1990, reforzó el carácter complementario de ambos territorios. Aunque la ciudad no ha recuperado su antiguo esplendor, el territorio costero se ha intensificado y diversificado como extensión funcional de la región capital.

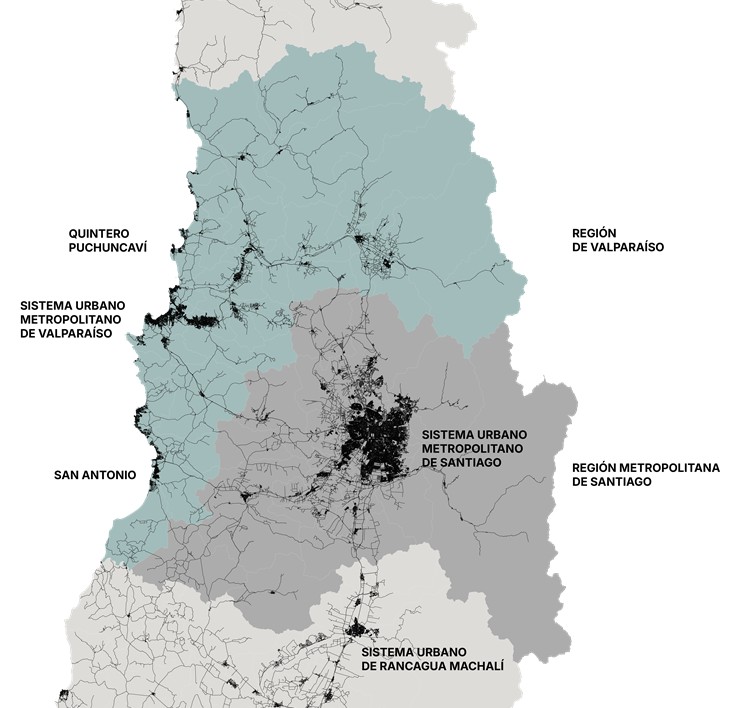

Hoy, Santiago , la capital nacional, articula el sistema urbano interregional más extenso del país, conformado junto con Valparaíso, San Antonio, San Felipe-Los Andes y Rancagua —territorio identificado históricamente como la “Macrozona Central de Chile”—, que concentra una porción significativa de la población, el PIB y el empleo nacional (Moris & Siembieda, 2021). Dentro de este sistema, el área metropolitana de Valparaíso constituye la segunda mayor aglomeración urbana del país, con aproximadamente 1,23 millones de habitantes (Censo 2024). Conformada por Valparaíso, Viña del Mar, Concón, Quilpué y Villa Alemana como núcleo central, e integrando funcionalmente a Quintero, Puchuncaví, Casablanca, Limache, Olmué, Quillota y La Calera, configura un territorio policéntrico donde la actividad portuaria ha sido históricamente estructurante.

La singularidad de Valparaíso radica en la superposición de su condición portuaria con su reconocimiento como Patrimonio de la Humanidad por la UNESCO en 2003. Esta doble identidad genera tensiones estructurales: la necesidad de modernizar la infraestructura para mantener competitividad internacional frente a puertos emergentes como Chancay, junto con la obligación de preservar los valores que fundamentaron su inscripción en la Lista del Patrimonio Mundial. El caso ilustra las contradicciones características del modelo chileno de desarrollo territorial, marcado por fricciones entre crecimiento económico y equidad, libre mercado y enfoque social, centralismo y descentralización.

El modelo portuario chileno, derivado de la reforma de 1997, estableció un esquema de “puerto arrendador” donde el Estado conserva la propiedad de la infraestructura mientras la operación se concesiona a privados mediante licitación pública, con plazos máximos de 30 años (Piraino et al., 2018; Weidenslaufer, 2023). Este modelo ha permitido importantes inversiones en modernización, pero ha generado desafíos en la coordinación puerto-ciudad, particularmente porque la legislación no contempló mecanismos de integración territorial ni consideró las especificidades de ciudades con valor patrimonial. La cultura de ajuste reactivo más que de planificación prospectiva, característica del modelo chileno, se refleja claramente en la trayectoria de Valparaíso.

Chile is going through a historic transformation towards economic decarbonization, where green hydrogen and renewable energies emerge as catalysts for change. Three strategic territories are leading this transition: the Antofagasta Region, with Mejillones as the industrial epicenter; the central macrozone – made up of the Metropolitan, Valparaíso and O’Higgins regions – which concentrates the main centers of consumption and productive sectors; and the Magallanes Region, with its exceptional wind potential and privileged access to global maritime routes. In this scenario, Valparaíso and its metropolitan urban system acquire renewed strategic relevance as a fundamental logistics node. Port cities face critical challenges—infrastructure obsolescence, operational congestion, and climate pressures—but simultaneously find opportunities in the blue economy, positioning themselves as nodes of global trade that must balance economic growth with territorial sustainability.

Understanding Valparaíso’s role in this transition requires placing it in its historical and territorial context. The city was erected as the “Jewel of the Pacific” from the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, functioning as the main center of commercial and financial exchange on the western coast of South America. Its decline began with the earthquake of 1906 and, crucially, with the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, which reoriented international shipping lanes. The regionalization process implemented during the military regime decisively configured a new relationship between Santiago and Valparaíso: the Metropolitan Region was delimited without a coastline precisely to enhance regional economic development to the west. This decision, together with the subsequent installation of the National Congress in Valparaíso in 1990, reinforced the complementary nature of both territories. Although the city has not recovered its former splendor, the coastal territory has intensified and diversified as a functional extension of the capital region.

Today, Santiago, the national capital, articulates the most extensive interregional urban system in the country, made up of Valparaíso, San Antonio, San Felipe-Los Andes, and Rancagua—a territory historically identified as the “Central Macrozone of Chile”—which concentrates a significant portion of the national population, GDP, and employment (Moris & Siembieda, 2021). Within this system, the metropolitan area of Valparaíso constitutes the second largest urban agglomeration in the country, with approximately 1.23 million inhabitants (Census 2024). Made up of Valparaíso, Viña del Mar, Concón, Quilpué and Villa Alemana as the central nucleus, and functionally integrating Quintero, Puchuncaví, Casablanca, Limache, Olmué, Quillota and La Calera, it configures a polycentric territory where port activity has historically been structuring.

The uniqueness of Valparaíso lies in the overlapping of its port condition with its recognition as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2003. This dual identity generates structural tensions: the need to modernize the infrastructure to maintain international competitiveness in the face of emerging ports such as Chancay, together with the obligation to preserve the values that founded its inscription on the World Heritage List. The case illustrates the characteristic contradictions of the Chilean model of territorial development, marked by frictions between economic growth and equity, free market and social focus, centralism and decentralization.

The Chilean port model, derived from the 1997 reform, established a “leasing port” scheme where the State retains ownership of the infrastructure while the operation is concessioned to private parties through public bidding, with maximum terms of 30 years (Piraino et al., 2018; Weidenslaufer, 2023). This model has allowed significant investments in modernization, but it has generated challenges in port-city coordination, particularly because the legislation did not contemplate territorial integration mechanisms or consider the specificities of cities with heritage value. The culture of reactive adjustment rather than prospective planning, characteristic of the Chilean model, is clearly reflected in Valparaíso’s trajectory.

Macro Zona Central de Chile. Sistemas urbanos de regiones de Santiago, Valparaíso y O’Higgins. (Fuente: Elaboración Roberto Moris, 2025).

Central Macro Zone of Chile. Urban systems of the of Santiago, Valparaíso and O’Higgins regions. (Source: Elaboration Roberto Moris, 2025).

Evolución de las relaciones puerto-ciudad (2000-2025)

Evolution of port-city relations (2000-2025)

Los últimos 25 años han sido testigo de transformaciones significativas en la relación puerto-ciudad de Valparaíso, marcadas por tres hitos fundamentales: la declaratoria patrimonial de 2003, la creación de mecanismos de coordinación institucional, y las reformas contemporáneas al sistema de planificación territorial. La inscripción en la Lista del Patrimonio Mundial marcó un punto de inflexión: si bien el reconocimiento internacional potenció el turismo y reforzó la identidad cultural porteña, también introdujo restricciones normativas que complejizaron proyectos de expansión portuaria. El área declarada incluyó sectores estratégicos del frente marítimo, generando zonas de fricción entre los requerimientos operativos del puerto y las exigencias de conservación patrimonial (ICOMOS, 2013).

La institucionalización del concepto Ciudad-Puerto se materializó a través de los Consejos de Coordinación Ciudad Puerto, espacios concebidos para armonizar intereses urbanos y portuarios mediante la participación de autoridades locales, empresas portuarias y representantes de la comunidad. En Valparaíso, este mecanismo ha permitido avances en proyectos específicos de regeneración del borde costero; no obstante, su efectividad ha sido limitada por la ausencia de facultades vinculantes y la fragmentación de competencias institucionales. Esta limitación refleja un patrón más amplio del sistema de planificación chileno: los dispositivos indicativos han fallado en cumplir su rol orientador, porque su cumplimiento no es obligatorio, abriendo posibilidades de ambigüedad en el régimen de planificación.

La Región de Valparaíso cuenta con el Plan Regulador Metropolitano de Valparaíso (PREMVAL) desde 1996, actualizado integralmente en 2014 y objeto de modificaciones parciales posteriores en materias de desarrollo industrial-portuario, gestión de riesgos naturales y ordenamiento de secciones territoriales mediante Planes Intercomunales Satélite. Por su parte, el nuevo Plan Regional de Ordenamiento Territorial (PROT), concebido para compatibilizar proyectos de escala regional bajo principios de sustentabilidad e integración social, permanece sin implementación en la región por falta de reglamento —situación que evidencia la desconfianza mutua entre quienes demandan certeza jurídica para el desarrollo industrial y quienes temen que este resulte insuficientemente regulado.

El período 2012-2024 intensificó tensiones estructurales acumuladas: expansión urbana extensiva de baja densidad, consumo acelerado de suelo rural y periurbano, crisis hídrica persistente, y conflictividad socioambiental aguda en zonas como Quintero-Puchuncaví —históricamente calificada como “zona de sacrificio” y hoy territorio emblemático de la transición energética nacional—. Estos procesos, agravados por la fragmentación institucional del Sistema Urbano Metropolitano, han incidido directamente en la postergación de proyectos estratégicos de infraestructura.

Tal es el caso de la expansión del puerto de Valparaíso, cuya viabilidad se articula actualmente en torno al “Acuerdo por Valparaíso”: un pacto suscrito entre la Empresa Portuaria Valparaíso (EPV), el Gobierno Regional y el Municipio, orientado a impulsar la ampliación portuaria mediante una inversión de US$850 millones destinada a duplicar la capacidad operativa hasta alcanzar 2,1 millones de TEUs anuales.

The last 25 years have witnessed significant transformations in the port-city relationship of Valparaíso, marked by three fundamental milestones: the heritage designation of 2003, the creation of institutional coordination mechanisms, and contemporary reforms to the territorial planning system. The inscription on the World Heritage List marked a turning point: while international recognition boosted tourism and reinforced the local porteño cultural identity, it also introduced regulatory restrictions that complicated port expansion projects. The declared area included strategic sectors of the waterfront, generating zones of friction between the port’s operational requirements and heritage conservation demands (ICOMOS, 2013).

The institutionalization of the Port-City concept materialized through Port City Coordination Councils, spaces designed to harmonize urban and port interests through the participation of local authorities, port companies, and community representatives. In Valparaíso, this mechanism has allowed for progress in specific waterfront regeneration projects; however, its effectiveness has been limited by the absence of binding powers and the fragmentation of institutional competencies. This limitation reflects a broader pattern in the Chilean planning system: indicative devices have failed to fulfill their guiding role because compliance is not mandatory, opening possibilities for ambiguity in the planning regime.

The Valparaíso Region has had the Valparaíso Metropolitan Regulatory Plan (PREMVAL) since 1996, which was fully updated in 2014 and subject to subsequent partial modifications in the areas of industrial-port development, natural risk management and the planning of territorial sections through Satellite Intercommunal Plans. For its part, the new Regional Territorial Planning Plan (PROT), designed to reconcile projects on a regional scale under principles of sustainability and social integration, remains unimplemented in the region due to a lack of regulation – a situation that shows the mutual distrust between those who demand legal certainty for industrial development and those who fear that it will be insufficiently regulated.

The period 2012-2024 intensified accumulated structural tensions: extensive low-density urban expansion, accelerated consumption of rural and peri-urban land, persistent water crisis, and acute socio-environmental conflict in areas such as Quintero-Puchuncaví – historically described as a “sacrifice zone” and today an emblematic territory of the national energy transition. These processes, aggravated by the institutional fragmentation of the Metropolitan Urban System, have had a direct impact on the postponement of strategic infrastructure projects.

Such is the case of the expansion of the port of Valparaíso, whose viability is currently articulated around the “Agreement for Valparaíso”: a pact signed between the Valparaíso Port Company (EPV), the Regional Government and the Municipality, aimed at promoting port expansion through an investment of US$850 million aimed at doubling operational capacity to reach 2.1 million TEUs per year.

Lecciones aprendidas

Lessons learned

El caso Valparaíso ofrece lecciones relevantes para otras ciudades-puerto que enfrentan desafíos similares de compatibilización entre desarrollo logístico, preservación patrimonial y calidad de vida urbana. La experiencia demuestra que los mecanismos de coordinación voluntarios y no vinculantes resultan insuficientes para abordar las tensiones estructurales entre puerto y ciudad. Se requieren instancias con capacidad decisoria real que integren las escalas nacional, regional, intercomunal y local, superando la fragmentación institucional característica del sistema actual. La gobernanza portuaria contemporánea no puede entenderse exclusivamente desde la eficiencia económica; requiere ser concebida como un sistema relacional donde confluyen intereses logísticos, urbanos, ambientales y ciudadanos en permanente negociación.

Un patrón fundamental del modelo chileno es la tensión entre centralismo y descentralización, con un estado presidencial unitario que opera esencialmente a través de una estructura sectorial. Esto conduce a inversiones segmentadas, no integradas, para alcanzar metas como la descentralización y la equidad. Los próximos instrumentos de planificación regional deberían tener una gobernanza capaz de integrar las diversas escalas territoriales, proporcionando métodos sensibles a las tendencias que condicionan las ciudades-región.

La desconexión histórica entre Planes Maestros Portuarios e instrumentos de planificación urbana ha limitado el potencial de proyectos conjuntos y ha generado conflictos evitables. La experiencia internacional de puertos como Rotterdam, Hamburgo, Barcelona o Singapur demuestra que la integración temprana de ambas lógicas de planificación es condición necesaria para el desarrollo sostenible, basada en coordinación institucional efectiva, participación ciudadana estratégica, flexibilidad normativa adaptativa y visión de largo plazo que trasciende ciclos políticos.

La experiencia chilena ofrece una lección adicional: durante la década en que se formalizó el Plan Regional de Ordenamiento Territorial (PROT), el Ministerio del Interior realizaba estudios en todas las regiones mientras il Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo (MINVU) continuaba diseñando Planes Regionales de Desarrollo Urbano (PRDU) en los mismos territorios, lo que resultó en la anulación mutua de ambos instrumentos.

La tensión entre patrimonio y desarrollo portuario puede transformarse en sinergia cuando se adoptan enfoques creativos de regeneración urbana. La reconversión de áreas portuarias históricas hacia usos mixtos, como ha ocurrido en casos europeos exitosos, permite preservar valores patrimoniales mientras se generan nuevas dinámicas económicas y sociales. Valparaíso tiene potencial para desarrollar un modelo propio que integre actividades portuarias modernas con regeneración urbana del borde costero histórico, transformando la declaratoria UNESCO de restricción percibida en un activo diferenciador.

The Valparaíso case offers relevant lessons for other port cities facing similar challenges in reconciling logistical development, heritage preservation, and urban quality of life. Experience demonstrates that voluntary and non-binding coordination mechanisms are insufficient to address the structural tensions between port and city. Bodies with real decision-making power are needed, integrating national, regional, inter-municipal, and local levels, overcoming the institutional fragmentation characteristic of the current system. Contemporary port governance cannot be understood solely in terms of economic efficiency; it must be conceived as a relational system where logistical, urban, environmental, and citizen interests converge in constant negotiation.

A fundamental pattern of the Chilean model is the tension between centralism and decentralization, with a unitary presidential state that operates essentially through a sectoral structure. This leads to fragmented, non-integrated investments aimed at achieving goals such as decentralization and equity. Future regional planning instruments should have governance mechanisms capable of integrating diverse territorial scales, providing methods sensitive to the trends shaping city-regions.

The historical disconnect between Port Master Plans and urban planning instruments has limited the potential of joint projects and generated avoidable conflicts. International experience with ports such as Rotterdam, Hamburg, Barcelona, and Singapore demonstrates that the early integration of both planning approaches is a necessary condition for sustainable development, based on effective institutional coordination, strategic citizen participation, adaptive regulatory flexibility, and a long-term vision that transcends political cycles.

The Chilean experience offers an additional lesson: during the decade in which the Port Master Plan (PROT) was formalized, the Ministry of the Interior was conducting studies in all regions while the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (MINVU) continued designing Urban Development Plans (PRDU) in the same territories, resulting in the mutual cancellation of both instruments.

The tension between heritage and port development can be transformed into synergy when creative approaches to urban regeneration are adopted. The conversion of historic port areas to mixed uses, as has occurred in successful European cases, allows for the preservation of heritage values while generating new economic and social dynamics. Valparaíso has the potential to develop its own model that integrates modern port activities with the urban regeneration of its historic waterfront, transforming the UNESCO designation from a perceived restriction into a differentiating asset.

Tendencias y visión de futuro

El futuro de la relación puerto-ciudad en Valparaíso estará determinado por la capacidad de articular respuestas a desafíos convergentes: la modernización del sistema de planificación territorial actualmente en curso, la adaptación al cambio climático y la transición energética, y la construcción de una gobernanza metropolitana efectiva que supere décadas de fragmentación institucional. Fundamentalmente, dependerá de comprender el rol estratégico de la región para el país y la macrozona central, en virtud de su infraestructura crítica portuaria y logística emplazada en las bahías de Valparaíso, San Antonio y Quintero-Puchuncaví.

La macrozona central, que concentra los principales centros de consumo y sectores productivos del país, constituye un territorio clave en la transición hacia una economía descarbonizada. La historia económica chilena ofrece lecciones cruciales: el ciclo salitrero del siglo XIX, basado en la explotación de recursos finitos, generó riqueza temporal pero no desarrollo territorial sostenible. Hoy, la abundancia energética renovable abre posibilidades inéditas para construir un paradigma donde la prosperidad económica se funda con la sostenibilidad ambiental (Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, 2025). Chile se ha convertido en líder mundial en energías renovables, con la meta de alcanzar el 60% de energía limpia para 2035.

La transición energética debe enmarcarse en crecientes desafíos ambientales. Se estima que Chile estará entre los 30 países con mayor riesgo hídrico del mundo: la falta de lluvia, el retroceso de glaciares y el exceso de derechos privados de agua configuran un futuro con estrés hídrico que requerirá gestión eficiente de la demanda, conservación de ecosistemas y nuevas fuentes de suministro. Para Valparaíso y la macrozona central, este desafío tiene implicancias directas para las operaciones portuarias y la sostenibilidad urbana, considerando que la producción de hidrógeno verde requiere importantes volúmenes de agua.

La visión de futuro contempla la evolución de Valparaíso hacia un Ecosistema Productivo Portuario Avanzado, caracterizado por integración multimodal efectiva, sostenibilidad y progresiva autonomía energética, cohesión social y urbana entre puerto y ciudad, gobernanza multinivel con participación ciudadana real, e infraestructura inteligente y resiliente. Este modelo supera la concepción del puerto como enclave para posicionarlo como componente integrado de sistemas territoriales que generan valor compartido.

El concepto de territorios inteligentes trasciende la digitalización urbana convencional, implicando crear espacios donde converjan industria energética, desarrollo tecnológico, investigación aplicada y emprendimiento innovador. Esta visión requiere superar la separación tradicional entre zonas industriales y urbanas, avanzando hacia modelos donde los polos productivos convivan armónicamente con ciudades de alto estándar. Las zonas de remodelación y los planes maestros de regeneración constituyen herramientas cruciales para la reconversión de áreas portuarias obsoletas hacia nuevas centralidades urbanas, siguiendo la experiencia de Santiago donde el creciente interés por vivir en áreas centrales con múltiples amenidades ha generado densificación en corredores de transporte y transformación del modelo de tenencia hacia el arriendo.

Chile es uno de los países con mayor exposición al cambio climático, dada su alta concentración y diversidad de desastres socio-naturales. Valparaíso, con su exposición a riesgos sísmicos, tsunamis, incendios forestales y eventos hidrometeorológicos extremos, requiere que la resiliencia urbana sea reconocida como herramienta para el desarrollo territorial. Uno de los temas pendientes es el trabajo a nivel comunitario: las comunidades organizadas con conocimiento de sus amenazas han demostrado mejor capacidad de respuesta, y en eventos mayores donde la operación metropolitana pueda verse afectada, el funcionamiento autónomo y colaborativo de barrios y comunas será crítico.

The future of the port-city relationship in Valparaíso will be determined by the ability to formulate responses to converging challenges: the ongoing modernization of the territorial planning system, adaptation to climate change and the energy transition, and the construction of effective metropolitan governance that overcomes decades of institutional fragmentation. Fundamentally, it will depend on understanding the region’s strategic role for the country and the central macrozone, given its critical port and logistics infrastructure located in the bays of Valparaíso, San Antonio, and Quintero-Puchuncaví.

The central macro-region, which concentrates the country’s main consumption centers and productive sectors, is a key territory in the transition to a decarbonized economy. Chilean economic history offers crucial lessons: the 19th-century nitrate boom, based on the exploitation of finite resources, generated temporary wealth but not sustainable territorial development. Today, the abundance of renewable energy opens unprecedented possibilities for building a paradigm where economic prosperity is founded on environmental sustainability (Ministry of the Environment, 2025). Chile has become a world leader in renewable energy, with the goal of reaching 60% clean energy by 2035.

The energy transition must be framed within growing environmental challenges. Chile is estimated to be among the 30 countries with the greatest water risk in the world: lack of rainfall, glacial retreat, and an excess of private water rights are shaping a future of water stress that will require efficient demand management, ecosystem conservation, and new sources of supply. For Valparaíso and the central macrozone, this challenge has direct implications for port operations and urban sustainability, given that green hydrogen production requires significant volumes of water.

The vision for the future envisions Valparaíso’s evolution into an Advanced Port Productive Ecosystem, characterized by effective multimodal integration, sustainability and progressive energy autonomy, social and urban cohesion between the port and the city, multilevel governance with genuine citizen participation, and smart and resilient infrastructure. This model transcends the concept of the port as an enclave, positioning it instead as an integrated component of territorial systems that generate shared value.

The concept of smart territories transcends conventional urban digitization, implying the creation of spaces where the energy industry, technological development, applied research, and innovative entrepreneurship converge. This vision requires overcoming the traditional separation between industrial and urban zones, moving towards models where production hubs coexist harmoniously with high-standard cities. Redevelopment zones and master regeneration plans are crucial tools for transforming obsolete port areas into new urban centers, following the example of Santiago, where the growing interest in living in central areas with multiple amenities has led to densification along transportation corridors and a shift in the tenure model towards rental housing.

Chile is one of the countries most exposed to climate change, given its high concentration and diversity of socio-natural disasters. Valparaíso, with its exposure to seismic risks, tsunamis, forest fires, and extreme hydrometeorological events, requires that urban resilience be recognized as a tool for territorial development. One of the pending issues is work at the community level: organized communities with knowledge of their threats have demonstrated a better capacity to respond, and in major events where metropolitan operations may be affected, the autonomous and collaborative functioning of neighborhoods and districts will be critical.

Reflexión final

Valparaíso encarna las tensiones y oportunidades que definen la agenda de las ciudades-puerto del siglo XXI a nivel global. Su condición patrimonial, lejos de ser un obstáculo insalvable, puede convertirse en el fundamento de un modelo distintivo de desarrollo portuario-urbano que integre eficiencia logística, preservación cultural y calidad de vida. En el contexto de la encrucijada histórica que enfrenta Chile, donde la transición energética ofrece la posibilidad de reescribir la trayectoria económica nacional, Valparaíso tiene la oportunidad de demostrar que la prosperidad económica, la preservación ambiental y el bienestar social no son objetivos en conflicto, sino dimensiones complementarias de un desarrollo territorial verdaderamente integrado.

El éxito de esta transformación dependerá de la capacidad para construir una gobernanza integrada y resiliente que supere la fragmentación institucional histórica, priorice inversiones en soluciones logísticas que liberen la presión sobre el tejido urbano patrimonial, y adopte una agenda de sostenibilidad capaz de transformar los pasivos ambientales heredados en oportunidades de innovación y beneficio social compartido. Para ello resulta fundamental avanzar hacia un Plan Ciudad Puerto de carácter estratégico que articule acciones de regulación, inversión, gestión y monitoreo bajo un enfoque colaborativo público-privado, aprovechando las capacidades tecnológicas que el país hoy dispone de manera inteligente y prospectiva.

Valparaíso puede evolucionar del puerto como enclave cerrado hacia el puerto como red territorial compartida, del control jerárquico hacia gobiernos multinivel deliberativos, del espacio clausurado hacia territorios porosos, co-creados y resilientes. Solo mediante esta transformación profunda la eficiencia logística se traducirá en equidad territorial duradera, honrando simultáneamente su legado patrimonial universal y su vocación portuaria fundacional que la ha definido por más de cuatro siglos de historia.

Valparaíso embodies the tensions and opportunities that define the agenda of 21st-century port cities globally. Its heritage status, far from being an insurmountable obstacle, can become the foundation of a distinctive port-urban development model that integrates logistical efficiency, cultural preservation, and quality of life. In the context of the historical crossroads facing Chile, where the energy transition offers the possibility of rewriting the national economic trajectory, Valparaíso has the opportunity to demonstrate that economic prosperity, environmental preservation, and social well-being are not conflicting objectives, but rather complementary dimensions of truly integrated territorial development.

The success of this transformation will depend on the ability to build an integrated and resilient governance that overcomes historical institutional fragmentation, prioritizes investments in logistics solutions that release pressure on the urban heritage fabric, and adopts a sustainability agenda capable of transforming legacy environmental liabilities into opportunities for innovation and shared social benefit. To this end, it is essential to move towards a strategic Port City Plan that articulates regulation, investment, management and monitoring actions under a collaborative public-private approach, taking advantage of the technological capabilities that the country has today in an intelligent and prospective manner.

Valparaíso can evolve from a closed enclave to a shared territorial network, from hierarchical control to deliberative, multi-level governance, from a sealed space to porous, co-created, and resilient territories. Only through this profound transformation will logistical efficiency translate into lasting territorial equity, simultaneously honoring its universal heritage and its foundational port vocation that has defined it for over four centuries.

IMAGEN INICIAL | Vista de la bahía de Valparaíso y su anfiteatro de cerros. (© Roberto Moris, 2011).

HEAD IMAGE | View of Valparaíso Bay and its amphitheater of hills. (© Roberto Moris, 2011).

╝

REFERENCIAS

REFERENCES

CENSO (2024). Censo de Población de Chile. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas.

ICOMOS. (2013). Report on the Advisory Mission to the Historic Quarter of the Seaport City of Valparaíso (Chile).

GORE Valparaíso (2025). Estrategia Regional de Desarrollo de Valparaíso. Gobierno Regional de Valparaíso.

Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. (2025). Estrategia Nacional de Transición Socioecológica Justa. https://mma.gob.cl/.

Moris, R., & Siembieda, W. (2021). The Santiago de Chile Metropolitan System: Transformative Tensions and Contradictions Shaping Spatial Planning. In The Routledge Handbook of Regional Design (pp. 194-213). Routledge.

Piraino, E., Lopez, M., & Moreno, C. (2018). Gobernanza e institucionalidad del sistema portuario chileno: aplicación a Puerto Valparaíso. PORTUS: The Online Magazine of RETE, 36.

Weidenslaufer, C. (2023). BCN Gestion de puertos comparado Chile y Peru.