╔

Over the course of more than half a century, the relocation of maritime and industrial activities away from city centres has fundamentally reshaped the relationship between cities and their waterfronts. From the 1960s onwards, technological change, containerisation and the development of deep-water ports led to the decline of traditional operational port functions, leaving extensive abandoned areas within historic waterfronts. In response, waterfront regeneration emerged as a key urban design and planning strategy, transforming former port areas into focal points for urban renewal, economic growth and place-making (Piga, 2022; Tommarchi, 2025).

The evolution of waterfront regeneration is commonly understood as occurring in distinct phases. Early projects, such as Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, prioritised leisure and tourism-led revitalisation (Breen and Rigby, 1996). A second phase, exemplified by large-scale interventions such as Barcelona’s Port Olímpic and Moll de la Fusta in the 1990s, emphasised mega-projects, global visibility and urban competitiveness (Bruttomesso, 2001; Giovinazzi and Moretti, 2010). More recent approaches, seen in HafenCity in Hamburg and Refshaleøen in Copenhagen, have sought to balance economic development with environmental quality, social inclusion and the reuse of historic port infrastructure through long-term, mixed-use planning (Hein, 2016; Karayilanoglu, 2019).

Across these phases, waterfronts have become strategically important urban environments, valued for their aesthetic appeal, symbolic significance and development potential. Planning strategies increasingly seek to integrate ecological restoration and environmental protection with market-oriented development pressures (Kinder, 2015). However, these processes often generate tension, as large-scale private investment frequently drives the transformation of former industrial waterfronts into exclusive districts, accelerating and the consequent displacement of the original communities (Butler, 2007; Rafaela Simonato Citron, 2021).

Within this context, waterfronts function as hybrid environments: simultaneously critical urban infrastructure and culturally and symbolically charged public spaces that shape urban identity, collective memory and social value (Piga, 2019). They also offer opportunities for economic revitalisation, cultural production, ecological renewal and climate adaptation (Jun and Song, 2023; Wu and Liu, 2023; Evans et al., 2022).

From the late 1970s, neoliberal urban governance reinforced market-led regeneration models, reframing cities as engines of growth and entrepreneurial competitiveness (Molotch, 1976; Harvey, 1989). Under this framework, planning increasingly facilitated private investment and accentuated the importance of an entrepreneurial view in the urban dynamics’ governance, while heritage and existing infrastructure were selectively preserved or aestheticized to enhance urban branding (Iovine, 2018).

It is within this global and theoretical context that the regeneration of the London Docklands can be understood. Once the world’s largest enclosed dock system, the Docklands entered decline following dock closures from 1969, before becoming the focus of a major regeneration programme led by the London Docklands Development Corporation in the early 1980s. This deregulated, market-led approach bypassed local democratic control and public consultation, treating the area as a development tabula rasa despite its communities, working industries and maritime heritage. While the Docklands redevelopment attracted substantial investment and reshaped London’s global image, it also generated controversy over social displacement, heritage loss and public accountability.

This article critically examines how maritime heritage was selectively retained within this neoliberal regeneration framework, arguing that conservation outcomes reflected market priorities rather than comprehensive urban continuity.

The Original London Docklands Maritime Landscape

By the late eighteenth century, London had emerged as one of the busiest ports in the world, yet its maritime infrastructure remained constrained by the linear geography of the River Thames. Cargo handling relied on open quays and wharves along the river, a slow and insecure system that became increasingly inadequate as trade volumes expanded. In response, a major reorganisation of port infrastructure was initiated in the 1790s through the construction of enclosed commercial docks, designed to provide secure and efficient environments for the storage and handling of goods. The first major schemes focused on the West India Docks on the Isle of Dogs and the London Docks at Wapping. These projects were promoted by the London Dock Company, formally established in 1796 by a consortium of bankers, merchants and shipowners, marking the beginning of one of the most ambitious civil engineering enterprises of the period (Rule, 2019). The creation of enclosed docks transformed both port operations and the urban morphology of London’s eastern waterfront.

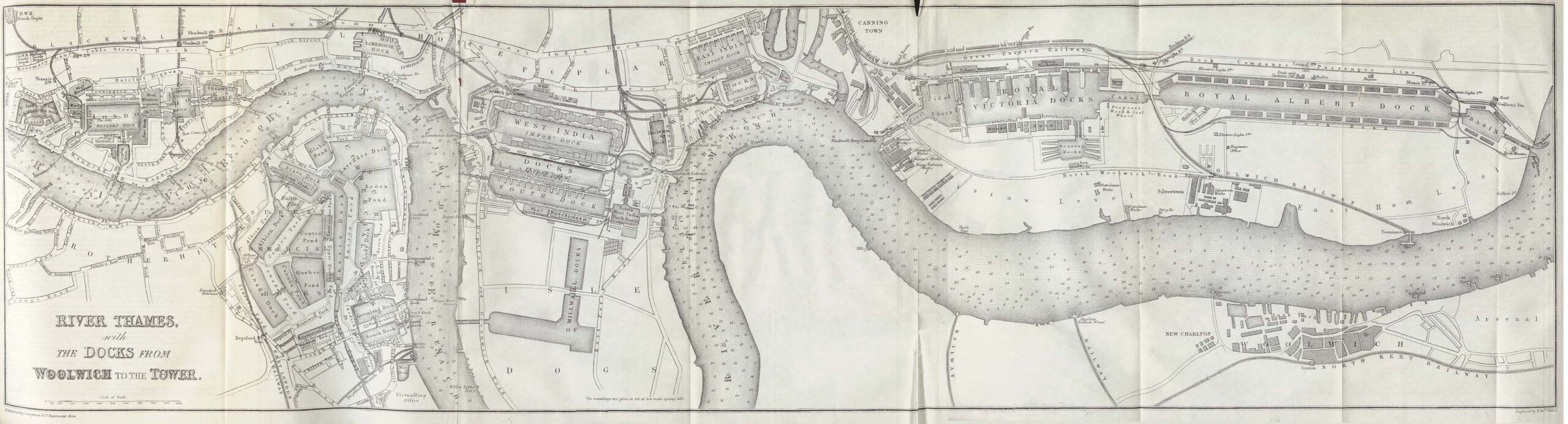

River Thames with the Docks from Tower Bridge to the Royal Docks in a 1882. (Source: Map by Edward Weller; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thames_river_1882.jpg).

Two key figures oversaw the realisation of the London Docks. Daniel Alexander, appointed surveyor in 1800, designed the warehouses and associated buildings, producing an architecture defined by classical proportion and functional clarity. John Rennie, one of the leading engineers of the era, supervised the construction of docks, basins, bridges and hydraulic infrastructure, giving the project an unprecedented scale and technical sophistication (Cruickshank, 2021).

The West India Dock, the first protected commercial wet dock, opened in 1802, followed by the London Docks official opening in 1805. The latter were connected to the Thames through three locked basins: Hermitage, Wapping and Shadwell, creating a controlled interface between river and dock. The complex comprised warehouses, vaults, perimeter walls and pumping stations, forming a highly integrated industrial system focused on efficiency, security and control.

Technological innovation was central to the design. Structures such as Tobacco Dock employed iron columns, wide structural spans and glazed roofs to maximise storage capacity, flexibility and ventilation. The Pennington Street Warehouses, with their extensive underground canteens and vaults extending beneath much of the dock estate, further exemplifies the functional integration that characterised early nineteenth-century dock architecture.

By the early twentieth century, however, technological and economic change undermined the viability of the London Docks. Steamships, increasing vessel size and, later, containerisation rendered the narrow basins obsolete. Following the relocation of port activity downstream to Tilbury, closer to the Thames Estuary, the London Docks closed in 1969, leaving a largely vacant and deteriorating landscape. By the early 1980s, only a small number of dock-related activities remained (Lunn, 2011; Marshall, 2018).

The Regeneration of London Docklands

The regeneration of London’s former docklands [1] east of the city centre began in 1981 with the establishment of the London Docklands Development Corporation (LCCD) and the designation of an Enterprise Zone in the Isle of Dogs under the Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher. This marked a decisive shift in the governance and planning of the former London Docklands, from locally accountable planning towards a centrally controlled, market-led model. The LDDC was granted exceptional statutory powers over an area stretching from Tower Bridge to the Royal Docks, displacing the authority of elected local councils and public bodies. Strong local opposition emerged, driven by the absence of clear proposals and meaningful provision for existing residents in terms of housing, employment and social infrastructure (Brownill, 2013).

From the outset, Docklands regeneration was controversial and widely criticised for its socially divisive effects. It became emblematic of developer-led gentrification, displacing established working-class communities in favour of a predominantly middle-class population (Brownill, 1990; Foster, 1999), while simultaneously being promoted as a model for high-density re-urbanisation (Urban Task Force, 1999). In the early 1980s, the Docklands still supported active docks, small industries, and a population of around 56,000 people, largely housed in council estates. Nevertheless, redevelopment strategies largely ignored this socio-spatial complexity, treating the area primarily as an underutilised economic asset, rather than as a complex socio-spatial landscape shaped by industrial and maritime labour, infrastructure and established communities (Leeson, 2018). Major projects, notably Canary Wharf’s concentration of office spaces aimed at contrasting the hegemony of the City of London [2], were advanced through streamlined approval processes that bypassed conventional planning scrutiny and public consultation (Tanis and Erkok, 2016).

This approach contrasted sharply with planning initiatives of the 1970s including the London Docklands Study Team (LDST) in 1971 commissioned by the Greater London Council (Parliament.uk, 2026), and the London Docklands Strategic Plan (LDSP) in 1976, produced by the Docklands Joint Committee. These earlier frameworks emphasised alternative redevelopment schemes for mixed housing provision, manufacturing and industry, in response to what the existing inhabitants required and how their skills could best be used, transport and the retention of water-based infrastructure [3], public access to the Thames and extensive community consultation (A London Inheritance, 2018).

As a matter of fact, under the leadership of its first chief executive, Reg Ward, the LDDC made a pivotal decision to stop the infilling of disused dock basins, which had already progressed throughout the London Docks and the Surrey Docks. This reinterpreted dock waters as spatial and visual assets, establishing the waterscape as a central organising element of redevelopment (Foster, 1999).

The appointment of Ted Hollamby [4] as chief architecture and planning officer signalled a tentative move towards a conservation-based and design-conscious approach. His 1982 design guide – not formally adopted by the LDDC – promoted formal geometries, symmetry, and structured landscapes that capitalised on retained dock infrastructure and was structured around a series of green axes forming continuous open spaces across reclaimed industrial land [5] (Hollamby, 1982; Edwards, 2013). Although influential, the guide lacked institutional support and was soon dismissed. Consequently, the early phase of redevelopment was characterised by a permissive, fragmented design culture, producing an architecturally incoherent and piecemeal urban landscape driven by state-facilitated market opportunity rather than design leadership.

A second phase emerged with the masterplanned development of Canary Wharf on the Isle of Dogs. This phase introduced detailed design codes as tools to support large-scale investment and place branding. However, the development functioned as a privatised enclave, socially and physically distinct from its surroundings. Initial failures in public transport provision and the financial collapse of its developer Olympia & York in 1992 exposed the limits of market-led regeneration, even as the scheme demonstrated the value of masterplanning within such a framework (Church, 1988).

From the early 1990s, large-scale public investment in transport infrastructure, particularly the Docklands Light Railway and the Jubilee Line Extension, proved critical in stabilising and reactivating Docklands regeneration. These interventions enabled the revival of Canary Wharf under new ownership – the Canary Wharf Group – and the completion of its masterplan (Feriotto, 2015). Despite improved urban design quality, regeneration remained uneven and socially divisive, with enclave-based development perpetuating socio-spatial fragmentation. When planning control passed to the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in 1998, significant physical and economic gains had been achieved, but without a coherent strategy for long-term social integration (Carmona, 2009).

From the early 2000s, the Docklands regeneration was influenced by new urban design principles introduced through the London Plan [6], which aimed to promote public health, equality of opportunity and sustainable development. Development expanded beyond Canary Wharf into the central Isle of Dogs, including the Millennium Quarter, partially replacing earlier suburban business park models. While local planning initiatives by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets sought to impose greater spatial coherence, their success was uneven, and lacked a compelling spatial vision. Despite this, the period was characterised by intense development activity, including high-density, mixed-use residential schemes and major commercial projects accompanied by substantial planning gain and social investment, reflecting a more pragmatic planning approach, seeking to balance state intervention and market forces through a combination of strategic intent and opportunity-led development (Florio and Brownill, 2000).

Viewed comparatively, the regeneration of London Docklands reveals a persistent tension between planning ideology, market forces, heritage, and the waterfront. Across successive phases, water and historic dock infrastructure shifted from being neglected, to symbolically retained, to tentatively recognised as potential anchors of continuity. However, regeneration was consistently driven more by market opportunity than by comprehensive planning, resulting in a heterogeneous, fragmented built environment oriented towards private space. This outcome reflects the political and cultural climate of the 1980s, and its particular emphasis on private enterprise, individual aspiration and market-led development that defined the Docklands experiment (Beswick, 2001).

The absence of an overarching design brief, combined with the London Docklands Development Corporation’s permissive regulatory regime, granted developers significant autonomy. This produced fragmented schemes with limited consideration of their wider urban and social context. Paradoxically, the prioritisation of market-led individualism ultimately generated a largely uniform and socially disconnected urban landscape (Butler, 2007).

London Docklands landscape viewed from Millwall Dock West Quay. (© Photo Giovanna Piga, 2025).

Maritime Landscape in London Docklands: Conservation, Erasure, Demolition and Infill

The regeneration of the London Docklands has involved extensive demolition, infilling and the erasure of maritime infrastructure, resulting in the substantial loss of its historic maritime landscape. These processes have profoundly altered the urban fabric, architectural character and, most notably, the spatial relationship between buildings and water. What remains today is not a coherent dockland environment but a fragmented assemblage of isolated structures, including warehouses, dock walls and ancillary maritime buildings (Webster, 2018).

Heritage retention has been highly selective. A limited number of buildings have been preserved, adapted and repurposed, predominantly for high-end residential and commercial uses. While their survival offers a degree of continuity with the site’s industrial past, this continuity is partial and largely symbolic, subordinated to a market-led redevelopment agenda that has prioritised offices and luxury housing over the preservation of the docklands as an integrated industrial landscape or the provision of amenities for existing communities (Babalis and Townshend, 2018).

Continuity with the historic maritime environment remains most legible where substantial warehouses and water spaces survive in close spatial association, notably in Wapping, Shadwell and the former West India Dock, where the scale, materiality and spatial organisation of the nineteenth-century dock construction are still traceable. Among these, Tobacco Dock stands out as the most architecturally legible survivor of the London Docks.

Tobacco Dock corner viewed from Wapping Lane. (© Photo Giovanna Piga, 2025).

Built between 1811 and 1813 to designs by Daniel Alexander and called Skin Floor for its use as a store for imported furs, its structure consists of a series of parallel glazed roofs with timber trusses supported on a cast-iron column framework and expansive undivided floor, including the fine brickwork vaults beneath the building that once extended under most of the quays of the London Docks, almost the only surviving examples, testifying the synthesis of architecture, engineering and merchandising that characterised the original dock warehouses. Although its original function has been lost, adaptive reuse for events and leisure has ensured its physical survival and architectural legibility (Lyders and Harrison, 1989; Historicengland.org.uk, 2026a).

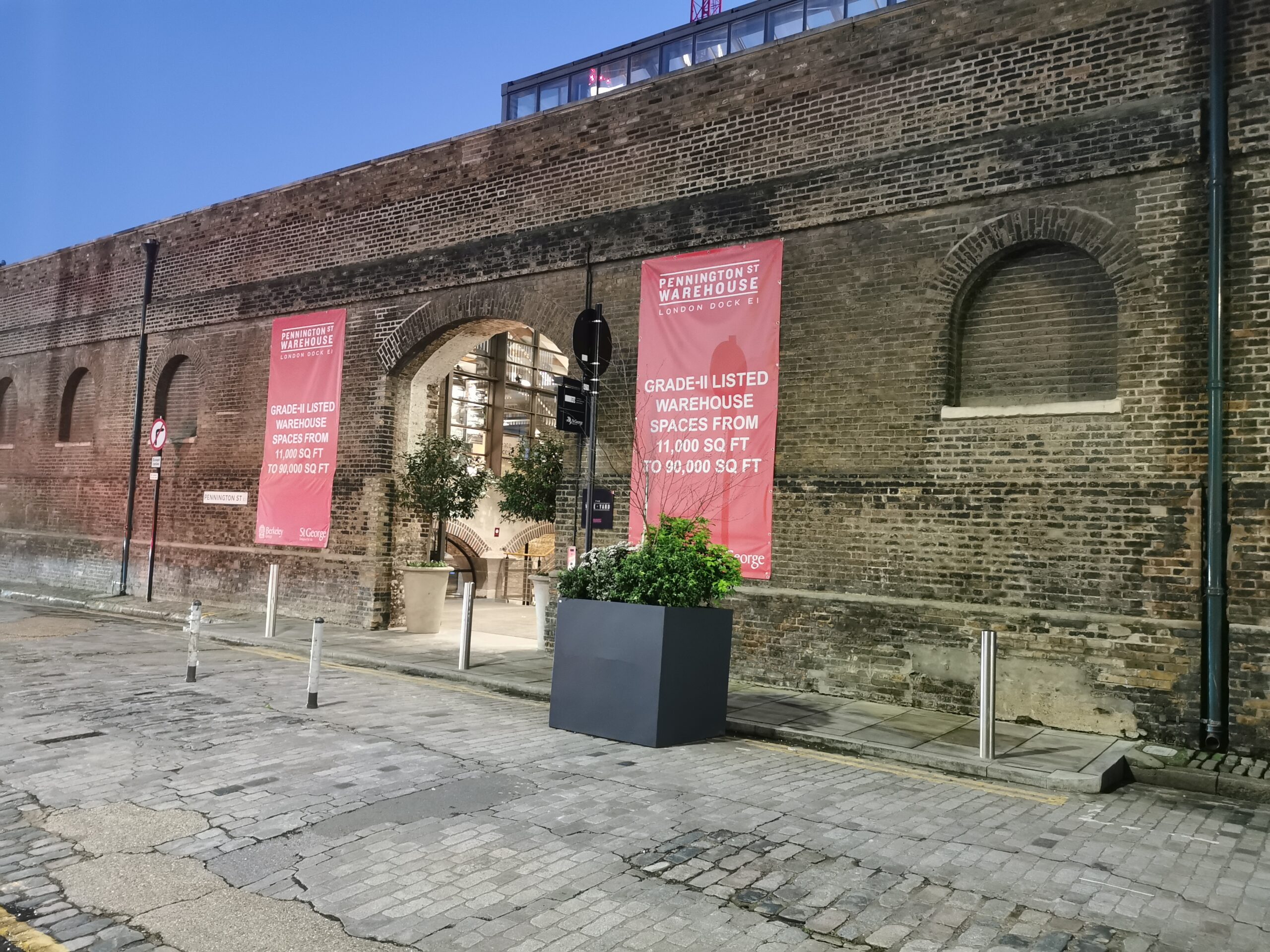

Nearby, the Pennington Street Warehouses represent another rare survival (Photo_03). Completed around 1804 and primarily used for the storage of goods, the two-storey warehouses are the only surviving parts of a much larger building. They featured a majestic ranges of canteens and vaults which, through interconnecting sections, linked with other vaults beneath the rest of the London Docks. Despite wartime damage and later alterations, their restoration and reuse in 2019 as office and cultural space have preserved much of their original structural character, including timber beams and spatial organisation. However, the wider dock infrastructure to which they once related has largely disappeared (Historicengland.org.uk, 2026b).

Pennington Street Warehouses viewed from Pennington Street. (© Photo Miki Fossati).

While the scale, materials and internal layouts of these surviving structures reflect the industrial character of the former Port of London and preserve tangible evidence of dockland construction and organisation, their present relationship with water is far less legible. At Tobacco Dock, the original dock basin has been reduced to an ornamental canal, mediating the building–water relationship and obscuring the historic waterscape. Surrounding residential development has replaced much of the former Pennington Street Warehouses, which were briefly occupied by artists’ studios before being taken over by the News International Group [7] in 1986 and later demolished following its departure in 2014 (Tower Hamlets, 2014). However, the spatial association between buildings and water still survives, and water spaces continue to act as carriers of continuity where original basin forms remain intact. Shadwell Basin, the largest surviving dock basin of the former London Docks, retains its physical outline and scale, serving as a spatial reminder of maritime activity within an otherwise predominantly residential context.

Shadwell Basin with the City of London in the background viewed from Wapping Wall. (© Photo Giovanna Piga 2025).

Shadwell Basin with Canary Wharf in the background viewed from Maynards Quay. (© Photo Giovanna Piga, 2025).

Elsewhere, water features such as the Wapping Ornamental Canal trace former dock connections between Tobacco Dock, Hermitage Basin and the River Thames, but now function primarily as decorative elements within privatised housing developments, limiting their capacity to convey the operational logic of the historic waterscape.

Wapping Ornamental Canal lined with housing developments viewed from Spirit Quay. (© Photo Miki Fossati).

In the Isle of Dogs, the only surviving Georgian warehouses of the West India Dock, Nos. 1 and 2, were converted into the Museum of London Docklands in 2003. Constructed in 1802 and designed by George Gwilt & Son to store sugar, rum and coffee, the warehouses were purpose-built for different cargoes across multiple storeys, and in front of each warehouse there was room for two West India ships to berth. WWII bombing in September 1940 most of warehouses, leaving only Nos. 1 and 2 intact. The buildings sat derelict for over twenty years after the closing of the West India Dock in 1980. This conversion project by Purcell Miller Tritton, represents one of the most sensitive examples of adaptive reuse in the area, with the museum’s design carefully preserving the monumental brick and timber structure while interpreting the social, economic, and colonial histories embedded within it (Museum of London Docklands, 2025).

Overall, Docklands conservation has favoured large, robust and visually distinctive structures, particularly warehouses and dock basins, while the finer-grained industrial fabric and systemic interconnections that once defined the port have largely been erased. The resulting heritage landscape consists of isolated monuments and water spaces that offer powerful but partial insights into the area’s maritime past, highlighting ongoing tensions between heritage conservation and neoliberal urban regeneration, and raising critical questions about how maritime identity is maintained, reinterpreted, or diluted in the transformation of former port landscapes to new public and private uses.

The Museum of London Docklands housed in the converted Georgian warehouses of West India Dock Nos. 1 and 2, viewed from West India Quay. (© Photo Giovanna Piga, 2025).

Conclusion

The regeneration of the London Docklands exemplifies the complexity and contradictions inherent in large-scale urban redevelopment and heritage conservation in a post-industrial context. Implemented through successive phases shaped by shifting political agendas and governance structures, the process has produced a fragmented urban landscape characterised by discontinuity and selective heritage retention.

This outcome is closely linked to the market-led regeneration framework pursued by the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC), in which heritage was treated primarily as an economic and symbolic asset. Conservation focused on large, adaptable and architecturally prominent structures, while less monumental but systemically significant elements of the dock infrastructure were demolished or infilled. As a result, heritage retention was neither comprehensive nor coherent, but curated to enhance place identity and property value.

Dock basins and water spaces were similarly transformed from working infrastructure into scenic amenities supporting high-end residential, office and leisure development. Although surviving buildings such as Tobacco Dock, the Pennington Street Warehouses and the West India Dock Warehouse provide tangible evidence of nineteenth-century dock construction and engineering, they now operate largely in isolation from the social, economic and logistical networks that once defined the port. The Docklands are therefore experienced not as a conserved maritime environment, but as a fragmented heritage landscape of isolated monuments and water features referencing a largely erased industrial past.

Overall, the Docklands represent a model of selective conservation in which continuity with the maritime past is maintained at the level of form and image, but detached from social memory and systemic coherence. While this approach has enabled adaptive reuse and preserved key structures, it has also produced a sanitised and depoliticised interpretation of dockland maritime landscape.

As cities continue to transform former industrial waterfronts, the Docklands offer a critical case study highlighting the need for more holistic approaches to maritime heritage that recognise port landscapes as interconnected urban systems embedded within wider social and spatial contexts.

HEAD IMAGE | London Docklands: Canary Wharf viewed from Wapping Thames Path. (© Photo Giovanna Piga, 2025).

╝

NOTES

[1] This comprised four sites: the Isle of Dogs and the London Docks in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets; Surrey Quays in the London Borough of Southwark; and the Royal Docks in the London Borough of Newham – so called because of the docks named after the royals Victoria, Albert and George V.

[2] The aim was to create a new financial district. Acting as an adviser to First Boston bank, G. Ware Travelstead commissioned a team of American architects led by Bruce Graham of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, who envisioned the scheme as a ‘mini-Manhattan on the Thames’. The project was ultimately realized by Olympia & York, a Canadian-American developer known for its role in the Battery Park City office complex in Manhattan (Fraser, 2007).

[3] The LDST plans are exhibited at the London Museum of Docklands. One particularly imaginative option, Waterside, involved developing an urban typology by shrinking the existing docks into a complex network of canals, which would connect new desirable housing constructed on the infilled land.

[4] Ted Hollamby – a socialist and member of the Communist Party – was appointed LDDC chief architecture and planning officer from 1981 to 1986.

[5] In a marked contrast to the influential LDSP plan of 1976, Hollamby’s proposal demonstrates a significant shift in priorities, favoring the formal design of walkways alongside retained dock infrastructure over the more naturalistic treatment of riverside paths. In this early approach the LDDC reinterpreted the post-industrial and maritime landscape, by capitalizing on its legacy of industrial driver, including its unique spatial organization of waterscape and land, through formalistic urban design and repurposing of the built heritage. Nevertheless, a clearer commitment to public riverside access emerged at a later point. By 1998, the LDDC’s Water Use Strategy formally asserted the Corporation’s intention to ensure public access to most quaysides and to the riverside throughout Docklands (Mountain, 2017).

[6] The Greater London Authority (GLA), established in 2000, provides strategic, citywide governance for London through a directly elected Mayor and Assembly. The mayor is responsible for strategic planning and must produce and regularly review the London Plan, formally known as the Spatial Development Strategy. The London Plan replaces earlier strategic guidance and requires borough development plans to be in general conformity with it. Under the GLA Act 1999, the Plan addresses only matter of strategic importance and must integrate cross-cutting themes of public health, equality of opportunity and sustainable development (Mayor of London, 2004).

[7] This was called ‘Fortress Wapping’ as Rupert Murdoch’s News International relocated from Fleet Street, the original location of the press industry in London, to a new, high-tech facility in Wapping, within the Pennington Warehouses, using automated printing. By 1988, nearly all the national newspapers had abandoned Fleet Street to relocate in the Docklands, and had begun to change their printing practices to those being employed by News International.

REFERENCES

A London Inheritance. (2018). London Docklands – A 1976 Strategic Plan. [online] Available at: https://alondoninheritance.com/london-history/london-docklands-a-1976-strategic-plan/ [Accessed 23 Jan. 2026].

Babalis, D. and Townshend, T.G. eds., (2018). c. Firenze: Altralinea Edizioni.

Beswick, C.A. (2001). Public-Private Partnerships. In: Urban Regeneratio. The Case of London Docklands. [MEDes (Planning) Degree in the Faculty of Environmental Design] Available at: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=Tt9tIzEAAAAJ&citation_for_view=Tt9tIzEAAAAJ:u5HHmVD_uO8C [Accessed 23 Jan. 2026].

Breen, A. and Rigby, D. (1996). The New Waterfront. A worldwide urban success story. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Brownill, S. (1990). Developing London’s Docklands. SAGE Publications Limited.

Brownill, S. (2013). Add water. Waterfront regeneration as global phenomenon. In: J. McCarthy and M.E. Leary, eds., The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration. London New York: Routledge, pp.45–55.

Bruttomesso, R. (2001). Cities on water and port waterfront projects. Città d’acqua e progetti sui waterfront portuali. Venezia: Marsilio.

Butler, T. (2007). Re-urbanizing London Docklands: Gentrification, Suburbanization or New Urbanism? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, [online] 31(4), pp.759–781.

Carmona, M. (2009). The Isle of Dogs: Thirty-five years of regeneration but have we seen a renaissance? In: Urban Design and the British Urban Renaissance. London: Routledge, pp.226–243.

Church, A. (1988). Urban regeneration in London Docklands: A five-year policy review. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 6, pp.187–208.

Cruickshank, D. (2021). Cruickshank’s London. A portrait of a city in 13 walks. London: Windmill Books.

Edwards, B.C. (2013). London Docklands: urban design in an age of deregulation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Evans, C., Harris, M.S., Taufen, A., Livesley, S.J. and Crommelin, L. (2022). What does it mean for a transitioning urban waterfront to ‘work’ from a sustainability perspective? Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 18(3), pp.349–372.

Feriotto, M. (2015). The regeneration of London’s Docklands: New riverside Renaissance or catalyst for social conflict? [Master Thesis] Available at: https://thesis.unipd.it/retrieve/5daca828-8cf9-4df0-8521-be195ecda60d/Tesi_Magistrale_Feriotto_Marianna_1046538_pdf.pdf [Accessed 23 Jan. 2026].

Florio, S. and Brownill, S. (2000). Whatever happened to criticism? Interpreting the London Docklands Development Corporation’s obituary. City, 4(1), pp.53–64.

Foster, J. (1999). Docklands. Cultures in conflict, worlds in collision. London: UCL Press – Taylor & Francis Group.

Fraser, M. (2007). London Docklands. Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London, [online] 5(1). Available at: http://www.literarylondon.org/london-%20journal/march2007/fraser.html. [Accessed 18 Dec. 2025].

Giovinazzi, O. and Moretti, M. (2010). Port Cities and Urban Waterfront: Transformations and Opportunities. TeMA – Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, 3(SP).

Harvey, D. (1989). From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, [online] 71(1), pp.3–17.

Hein, C. (2016). Port cities and urban waterfronts: how localized planning ignores water as a connector. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 3(3), pp.419–438.

Historicengland.org.uk. (2026a). A Warehouse (Skin Floor) Including Vaults Extending Under Wapping Lane, Non Civil Parish – 1065827 | Historic England. [online] Available at: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1065827?section=official-list-entry [Accessed 21 Jan. 2026].

Historicengland.org.uk. (2026b). Pennington Street Warehouses (Including Former Canteen and Vaults Below), Non Civil Parish – 1065825 | Historic England. [online] Available at: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1065825?section=official-list-entry [Accessed 21 Jan. 2026].

Hollamby, E. (1982). Isle of Dogs: a guide to design and development. London: London Docklands Development Corporation.

Iovine, G. (2018). Urban regeneration strategies in waterfront areas. An interpretative framework. Journal of Research and Didactics in Geography (J-READING), 1, pp.61–75.

Jun, J. and Song, M. (2023). Study on the Redevelopment of the Hangang River Waterfront from an Urban Resilience Perspective. Sustainability, [online] 15(19), p.14249.

Karayilanoglu, G. (2019). Adaptive reuse of waterfront industrial areas: example of Refsalehøen in Copenhagen. In: 1st International Symposium of Design for Living with Water.

Kinder, K. (2015). The politics of urban water: changing waterscapes in Amsterdam. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

Leeson, L. (2018). Our land: creative approaches to the redevelopment of London’s Docklands. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(4), pp.365–379.

Lunn, G. (2011). Port of London Through Time. Amberley Publishing Limited.

Lyders, C. and Harrison, A. (1989). Docklands heritage: conservation and regeneration in London Docklands. London: London Docklands Development Corporation.

Marshall, G. (2018). London’s Docklands. An illustrated history. New edition ed. The History Press Ltd.

Mayor of London (2004). The London plan: Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London. London: Greater London Authority.

Molotch, H. (1976). The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place. American Journal of Sociology, 82(2), pp.309–332.

Mountain, D. (2017). Transforming the urban? The adaptive reuse of infrastructure in the London Docklands Development Corporation. MSc in Urban Studies at University College London.

Museum of London Docklands. (2025). Museum of London Docklands. [online] Available at: https://programme.openhouse.org.uk/listings/1148 [Accessed 21 Jan. 2026].

Parliament.uk. (2026). London Dockland Study Group (Report) – Hansard – UK Parliament. [online] Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1973-01-22/debates/6658710c-d94a-4aeb-8e89-c7ce607cf8fb/LondonDocklandStudyGroup(Report) [Accessed 16 Jan. 2026].

Piga, G. (2019). Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey (UK): Conservation and reuse of the Royal Naval Dockyard. Portus: the online magazine of RETE, [online] (37). Available at: https://portusonline.org/sheerness-on-the-isle-of-sheppey-uk-conservation-and-reuse-of-the-royal-naval-dockyard/.

Piga, G. (2022). Waterfront Design in Small Mediterranean Port Towns. London and New York: Routledge.

Rafaela Simonato Citron (2021). Urban regeneration of industrial sites: between heritage preservation and gentrification. WIT Transactions on the Built Environment, 203.

Rule, F. (2019). London’s Docklands: a history of the lost quarter. The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud: The History Press.

Tanis, F. and Erkok, F. (2016). Learning from waterfront regeneration project and contemporary design approaches of European port city. In: History Urbanism Resilience. 17 IPHS Conference Port, Industry and Infrastructure. pp.151–161.

Tommarchi, E. (2025). Waterfront Redevelopment Five Decades Later. An Updated Typology and Research Agenda. Ocean and Society, 2(9265), pp.1–17.

Tower Hamlets. (2014). Former News International Site, 1 Virginia Street, London, E98 1XY (PA/13/01276 and PA/13/01277). [online] Available at: https://democracy.towerhamlets.gov.uk/mgAi.aspx?ID=48431.

Urban Task Force (1999). Towards an Urban Renaissance. [online] London: Taylor & Francis Group. Available at: https://www.35percent.org/img/urban-task-force-report.pdf Final Report of the Urban Task Force. Chaired by Lord Rogers of Riverside.

Webster, P. (2018). London’s Docks 1971 – 2020. A photographic record by Paul Webster with original prints for sale. [online] London’s Docks. Available at: https://londonsdocks.com/ [Accessed 27 Dec. 2025]. Wu, Y. and Liu, Y. (2023). Transforming Industrial Waterfronts into Inclusive Landscapes: A Project Method and Investigation of Landscape as a Medium for Sustainable Revitalization. Sustainability, 15(6), p.5060.