Since the nineteenth century, the industrial revolution has produced substantial transformations in the urban structure, closely related to the technological evolution of transport system, that have forced the city to reserve the space available and necessary to the railway, the port, the tram, the car, resulting in a reduction of the public spaces in monofunctional and technical spaces, devoid of social values, cultural and symbolic of the historic city.

The trend towards a separation of production activities, commercial, residential and service, has profoundly changed over time the intrinsic nature of the public space, which takes its vitality from the functional mix, the opportunities for relations and exchange.

The processes of functional specialization, privatization of spaces for collective use and “residential segregation”, that characterize the contemporary urban growth, have accentuated the relational fragmentation process and spatial dispersion.

This situation, if one side has called into question the concept of public space – intended as a place multifunction with open access – around which was articulated the city structure and the relationships of the entire community, the other side has highlighted the need to restore value to public space as a place of sociability and recognition of community identity, in which is exercised the democratic right to use the city, while respecting the right of use of the other and especially of future generations.

Pirrama Park, Sydney, Australia. (Hill Thalis Architecture, Aspect Studios & CAB Consulting)

The concept of public space

The public space is defined as any place of public property or public use accessible and usable to everyone free of charge and non-profit. The right to access and use in full freedom is permitted within the rules of a civil coexistence, respectful and responsible. As they equipped with physical, historical, environmental, social and economic characteristics, the public spaces represent the “places” of the community life and are important to the individual and social wellbeing; they are expression of the diversity of their common heritage, cultural and natural, and basis of their identity (European Landscape Convention).

Not necessarily the public spaces are or have to be public property, but those that are also public property offer guarantees longer lasting about their accessibility and use over time, as they are less subject to legitimate changes of functional use from private property.

Specifically, it is possible to distinguish between: spaces that have an exclusively or predominantly functional character; spaces that presuppose or promote a use of individual type; and finally spaces that have a prevalent role of factor of social aggregation, related to particular forms of interaction between function, form, sense, and/or to the relationship between the built and non-built.

Kalvebod Waves, Conpenhagen, Denmark. (KLAR and JDS/Julien De Dmedt Architects)

Today to constitute a valuable resource and a great opportunity are the “potential public spaces” – ie areas of public property, not accessible and/or usable – on which you can build integrated policies for the strengthening of existing public space, the morphological and functional redevelopment of the urban fabric and public heritage abandoned, the economic and social regeneration, and the improvement of the life quality.

New ways to re-claim the public space

During the last few decades have been launched various policies and actions for the public space recovery and regeneration, aimed to give back to social life such places, make urban centers more sustainable, and at increasing the competitive factors of the city by improving its overall image.

The right to a free use of quality public spaces is today strongly re-claimed by numerous movements and by the citizens themselves; the greater influence of civil society in the urban space management has generated new approaches and innovative design tools (integrated planning, public participation, etc.) which provide for the involvement of citizens. The process of re-definition of these areas and urban fragments, on one hand based on the promotion of diversity and the other on the resilience and innovation, have the purpose to return a sense of place and a better quality of life.

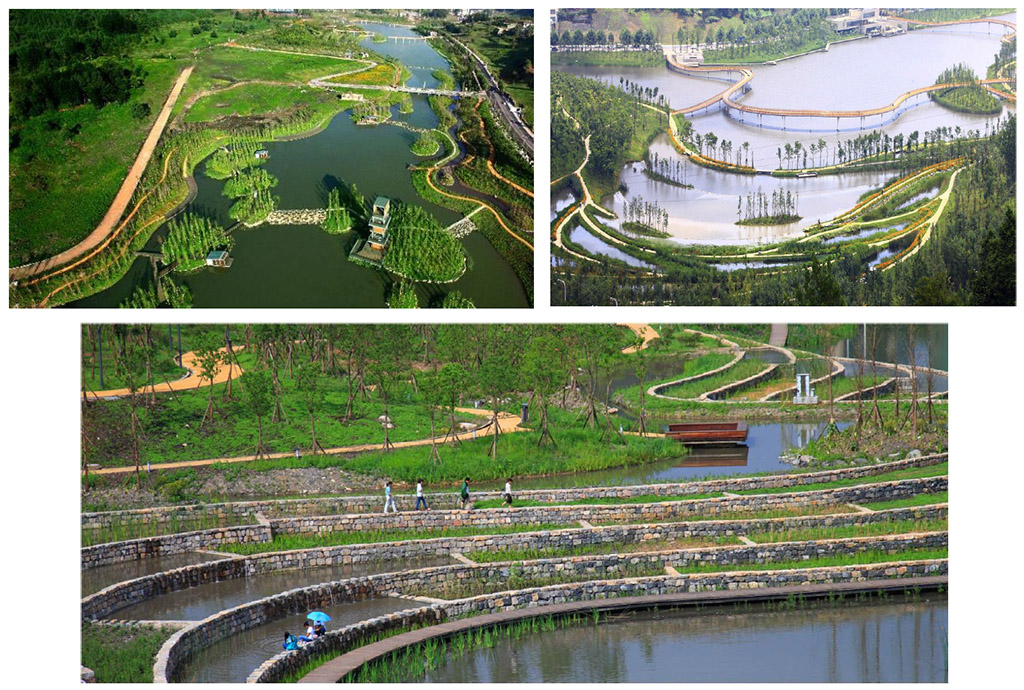

Zhangjiagang Town River Reconstruction, Zhangjiagang, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China. (Botao Landscape)

New methods to raise public awareness and for reclaiming the urban commons start from the identification and enhancement of collective behavior, which are reworked in order to increase the opportunities and the quality not only of the space but also of the life, to get to explore new ways, creative and innovative, to imagine the public space planning and management. The objective is to propose inclusive design strategies, that allow for temporal occupation of the space, integrating different groups and interests from the common perceptions of the public space, and encouraging social negotiation and civic participation.

It is a great challenge that requires to take into account the environmental and socio-economic needs of contexts considered, in an ongoing dialogue with the community that involves primarily local governments, and public and private interests of associations, residents, owners , investors, etc.

Pier C Park, Hudson River Waterfront Walkway, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA. (Apollonis Wang)

The presence of public space in the cities. The role of urban planning

Integral part of the architecture and the urban landscape, heritage of individual and collective memory, the public space as place multifunctional has a decisive role on the overall image of the city and community life. In this sense, the design of public space deserves a special attention.

To analyze the overall conditions of the places (physical, environmental, climate, topography, etc), allows to recognize the existing issues, and assess the extent and type of social interaction between users. In this way you can identify the functional requirements and the conditions to fulfill, finally, define the design components, also for an eventual temporary use.

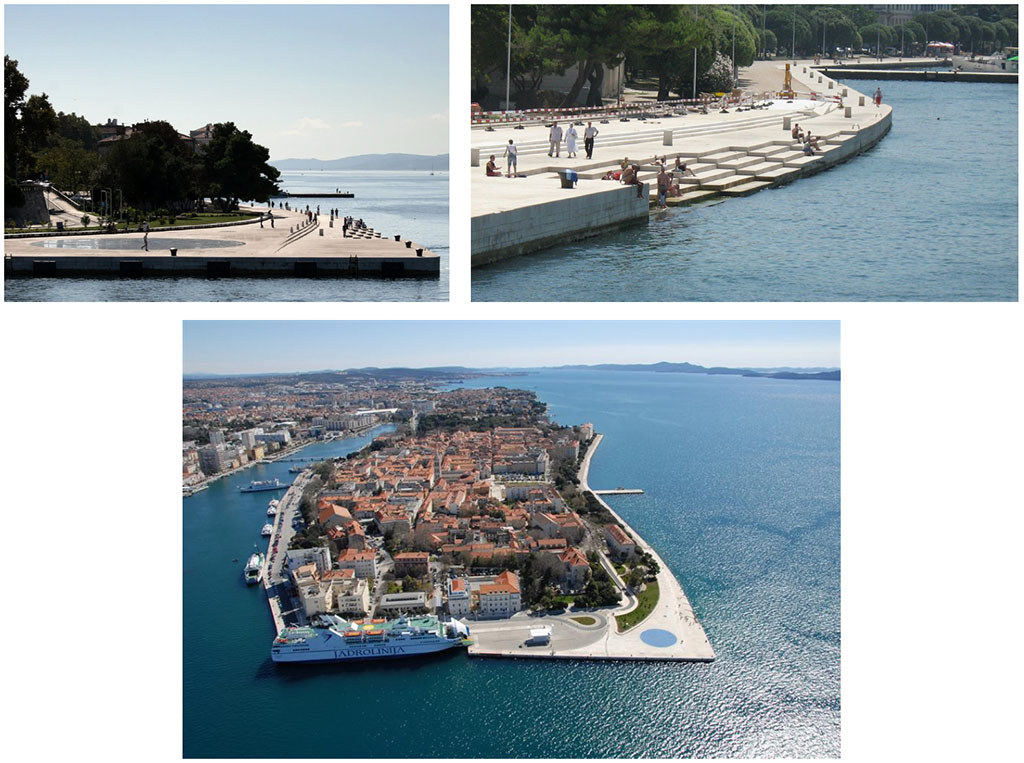

“Morske Orgulje” Sea Organ, Zara, Croazia. (Nikola Bašić)

The project proposal must be conceived in reference to a “landscape in interaction” destined to different users, promoting and facilitating the relationships between the subjects and the use of space. This is possible by working on different scales, opening new views and perspectives, creating porosity, making the place efficient and lively, increasing the services quality and variety, improving accessibility and lighting, etc.

Key topics for the planning are stakeholders involvement and governance, the public space role of “catalyst” as socio-economic transformations, the selection of intended uses, the creation of inclusive places (arts, history, heritage, leisure, etc.), the architectural choices and urban design, the improvement of connections, technological innovation, new forms of investment, the safety, etc.

These are generally medium-long term projects, which need time to ensure a transformation of quality, with sustainable and competitive solutions, that attract economic interest and the best talent from around the world, that increase the demand for residential housing and the real estate value, to promote urban regeneration of the adjacent areas, but at the same time with efficient operations in terms of management.

Minghu Wetland Park, Liupanshui, Guizhou, China. (Turenscape)

The water and the public space for the sustainable development of coastal communities

The city on the water can enjoy the benefits associated with the presence of a valuable resource and a landscape of great charm. In particular, the coastal communities have a distinct sense of place created by their history and geographic location. The love for the “water” element has grown throughout history, along with the ability to defend themselves and to adapt to its nature; the water has left its mark in many modes in the urban centers, along the rivers and canals, in the harbor areas, where often the abandoned docks in a state of decay were recovered in new destinations functional without forgetting their industrial past.

Living on the water historically has been often convenient, sometimes hazardous, but always desirable, and should remain so. Bordered by water, the people of the waterfront is called to protect natural resources, history of the community, heritage left by the abandoned activities and maritime identity from the effects of urban growth and of human intervention.

Riverside Park South Waterfront, New York, USA. (Thomas Balsley Associates)

Nowadays make accessible the waterfront of the city, creating new public spaces to serve the local community and visitors, can become an opportunity.

The potential of public and private investment on the waterfront is evident – as well compared to the growth forecast of the urban population in the future (10-20 years, in particular in Africa and Asia) – as indeed in recent decades there has been a strong interest in the areas redevelopment in a state of neglect and decay, that has produced interesting results in the time, in terms of the economic, social and ecological development and the image for the cities on the water. Alongside the construction of residential complexes, commercial galleries, business districts and cultural spaces, the plans for the waterfront development and regeneration necessarily have to incorporate new public spaces and open places, accessible to the public and of quality, integrated and connected with the urban fabric by public transport (also on water, sometimes more efficient and cost-effective) or pedestrian paths, experimenting in addition innovations and advanced technologies.

Is also possible to re-imagine new water landscapes not only in terms of urban regeneration, economic investment, revaluation of real estate, but also in terms of protection and safety for the whole community (drainage, microclimate, biodiversity, etc.). The public spaces overlooking the water can be designed in function of climate change and extreme events that produce, so as to ensure greater urban resilience. Similarly, in areas destroyed or severely affected by catastrophic events, the public spaces can play a key role in the implementation of the reconstruction process and recovery of community life.

Hornsbergs Strandpark, Stockholm, Sweden. (Nyréns Arkitektkontor)

Certainly it is needs a balanced approach in reconnecting the city to its waterfront to increase its value and investment opportunities, and at the same time to create a new landscape that has to be charming and accessible to the public, sustainable and resilient.

To ensure a sustainable growth and intelligent development, and to return a sense of place to coastal communities, a strategic approach to the urban regeneration of the waterfront needs to be oriented to:

- restore the biological and physical structure of the water edge and shoreline, as far as possible;

- enhance the image of land-water interface and surrounding landscape;

- allocate areas and spaces for cultural and social program, activities aimed for fun and leisure, uses and public utilities;

- rethink processes, tools, and methods to re-imagine these urban spaces, their shapes and intended uses in a multi-scalar dimension which must take account of the context roots and the relational dynamics with the territory.

Quais Rive Gauche de la Garonne, Bordeaux, France. (Atelier Corajoud)

Re-imagine the public space on the waterfront

An edge water can take so multiple forms, it can offer and propose different opportunities for fruition, arouse a variety of public and private interests, for business or leisure, however the special attention should relate to the specific context and cultural identity, the ability to exploit in an intelligent, innovative and creative mode the “water” element (and, where there are, other components of the natural environment), to enhance the landscape and preserve the distinctive features of the place.

Sugar Beach, Toronto, Canada. (Claude Cormier Landscape Architects)

Among the functions and the spaces of public interest that can be located on the waterfront:

- Access routes to the coast that unify the landscape and are an important element in the system of inter-connection between the waterfront, urban fabric, open areas, public and private spaces, etc.;

- Walkways that crossing the public spaces and the natural landscape ensure the direct access to the water and often extraordinary views;

- Piers and docks requalified, often intended exclusively to public access and recreational functions;

- Natural parks and open areas, realized to preserve or restore the natural environment of the coast, can be used as spaces for contemplation and exploration of the water landscape;

- Urban parks that are designed to accommodate artificial elements (architecture, urban design, landmark, etc.) and a wide variety of uses that allow to appreciate the proximity of waterfront;

- Areas for recreational activities on water which enable physical access to the waterfront for the practice of water activities and sports;

- Water basins, used for different purposes (recreational, commercial, acquatic, etc.) offer opportunities to view and enjoy the waterfront and its attractions.

Paseo maritimio de la Playa de Poniente, Benidorm, Spain. (OAB – Office of Architecture Barcelona, Carlos Ferrater Lambarri and Xavier Martí)

The choice of functional mix, the presence of public space, a flexible planning – therefore can adapt to the specific context and to changing circumstances – represent generally the best solution (and desirable) to ensure the waterfront development even in a future situation which may differ from the current state.

Generally the public access and usability of the waterfront are more guarantee in the cases where the following aspects are potential and enhanced: continuity, through paths that connect water edges, open spaces, public places and activity and service areas; sequentiality of large open spaces from which it is possible to appreciate significant water views; a variety of uses and spaces that offer different opportunities to spend the time and enjoy the landscape; integration through connections, frequent and comfortable, with the city and the surrounding area; last but not least, specificity or rather a character and a sense that the architectural and urban design choices are able to restore to the place taking advantage of the landscape, history, heritage and local identity.

In this sense, re-imagine the urban waterfront is a complex process that requires the involvement of many stakeholders, experts in different disciplines (planners, urban planners and architects, landscape designers, sociologists, market investment and capital specialists, etc.)

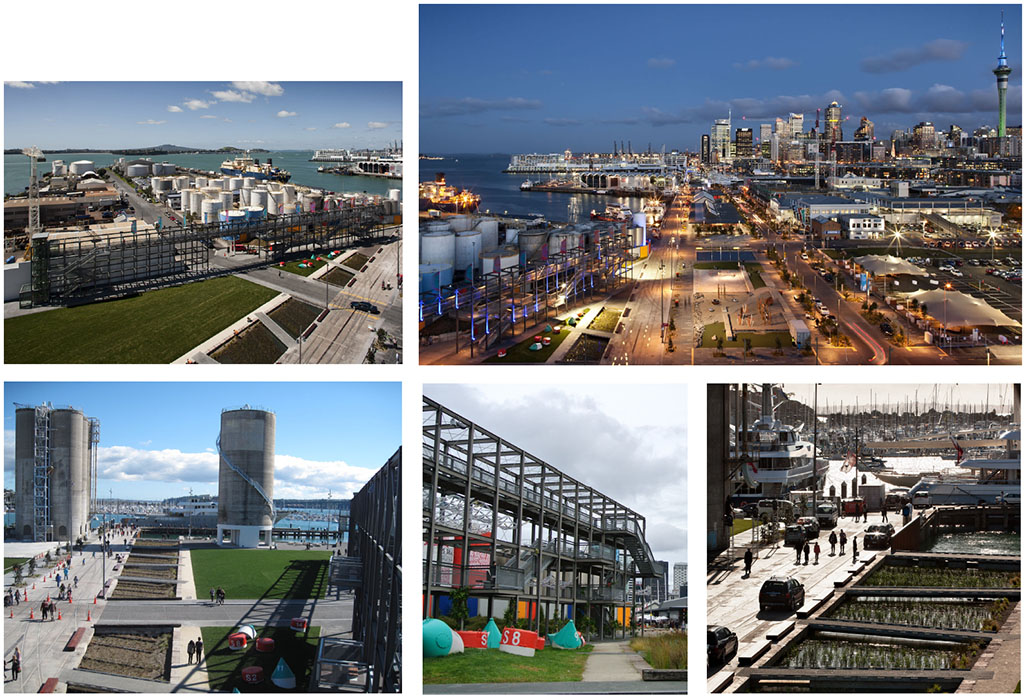

North Wharf Promenade, Silo Park and Jellicoe Harbour, Auckland, New Zealand. (Taylor Cullity Lethlean & Wraight + Associates)

Determinant in the process is the involvement of different interested stakeholders, the transfer of knowledge, as well as the public participation. Are the citizens and users that have to propose new ways of “re-appropriation” of the waterfront and to public use of the space overlooking the water; needs and desires that other persons, depending on the specific skills and expertises, will have to transform into a planning and design concrete, aimed at the realization.

To propose a “successful solution”, the different stakeholders should coordinate their efforts in an integrated approach, that requires a clear vision, shared objectives, a flexible attitude, and the cooperation among government agencies, private companies, experts, consultants, owners, investors, residents , etc.

Anchor Park, Västre Hamnen, Malmö, Sweden. (SLA, Stig L. Andersson)

Among the main purposes of this approach:

- the opening of the waterfront to the public;

- a planning/design that should be open and participatory, take into account local conditions and the complex needs of final users, help to re-imagine “fragments” of city;

- the realization of public spaces a human-scale, pedestrian, sociable, lively and fun;

- the construction of cultural complex, urban landmark, spaces for socializing and leisure, in connection between them and with the surrounding area;

- the creation or enhancement of context specific characteristics, proposing an original and exclusive image of the areas, to make more attractive and comfortable the places;

- the development of new activities and employment, new interests and values, attracting resourceful people and businesses;

- a built landscape that should protect and enhance the resources and the tangible and intangible heritage (natural, historical, architectural, etc.) and also should be adaptable to changing circumstances, in order to avoid costly mistakes that would weigh on future generations.

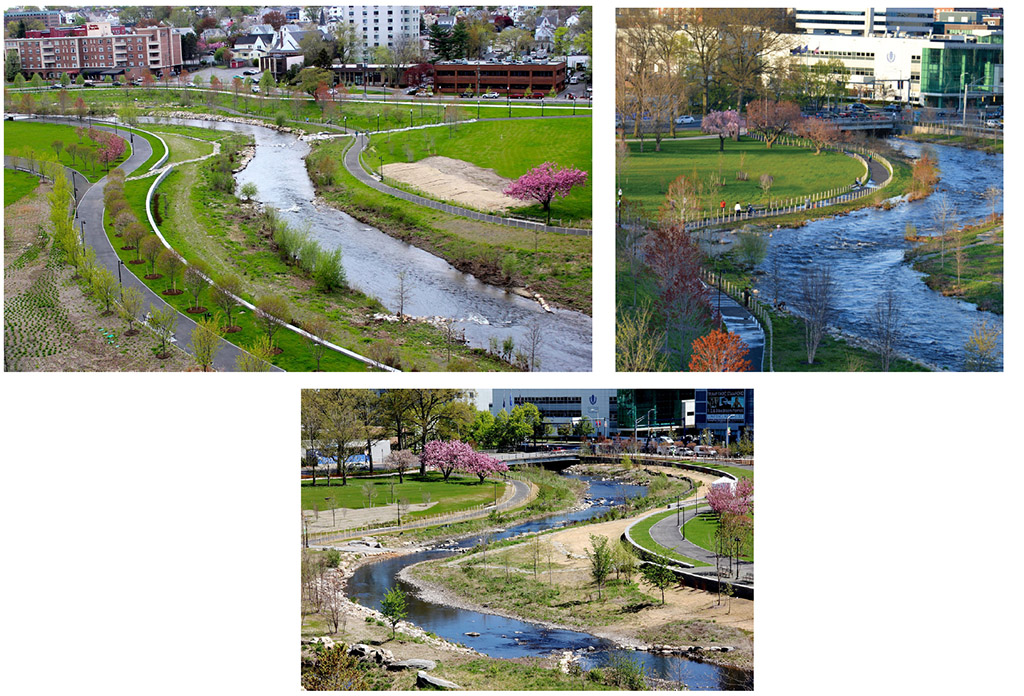

Mill River Park and Greenway, Stamford, Connecticut, USA. (OLIN)

The added value produced by the urban transformation and the new public access on the waterfront should lead to the overcoming of conflicts and the various interests on areas

The public space is a resource and a great potential to implement transformation processes in urban areas, in particular in contexts characterized by “strong and identifiable” landscape components and values – as the land-water interface – by the presence of places particularly suited to the construction of functional centralities and relationship systems, in which you can re-imagine new development opportunities in a temporal and spatial continuity that allows to return the identity to the places.

Head image: El Palmeral de las Sorpresas, Málaga, Spain. (Junquera Arquitectos; Photo: Oriana Giovinazzi)

Re-immaginare gli spazi pubblici. Nuove opportunità di sviluppo sull’acqua

A partire dal XIX secolo la rivoluzione industriale ha prodotto consistenti trasformazioni nella struttura urbana, strettamente legate all’evoluzione tecnologica dei sistemi di trasporto, che hanno costretto le città ad adattare gli spazi disponibili e necessari alla ferrovia, al porto, al tram, all’automobile, con una conseguente riduzione degli spazi pubblici a spazi monofunzionali e tecnici, privi dei valori sociali, culturali e simbolici della città storica.

La tendenza ad una separazione delle attività produttive, commerciali, residenziali e di servizio, ha profondamente modificato nel tempo la natura intrinseca dello spazio pubblico, che trae la sua vitalità dal mix funzionale, dalle opportunità di relazione e di scambio.

I processi di specializzazione funzionale, la privatizzazione degli spazi ad uso collettivo e la “segregazione residenziale”, che caratterizzano la crescita urbana contemporanea, hanno accentuato il processo di frammentazione del tessuto relazionale e la dispersione territoriale. Questa situazione se da un lato ha messo in discussione il concetto di spazio pubblico – inteso come luogo polifunzionale ad accesso libero – attorno al quale ruotava la struttura della città e le relazioni dell’intera comunità, dall’altro ha evidenziato la necessità di restituire valore allo spazio pubblico inteso come luogo della socialità e di riconoscimento dell’identità comunitaria, in cui si esercita il diritto all’uso democratico della città, nel rispetto del diritto d’uso degli altri e soprattutto delle generazioni future.

Pirrama Park, Sydney, Australia. (Hill Thalis Architecture, Aspect Studios & CAB Consulting)

Il concetto di spazio pubblico

Lo spazio pubblico è definibile come “ogni luogo di proprietà pubblica o di uso pubblico accessibile e fruibile a tutti gratuitamente e senza scopi di lucro”. Il diritto di accesso e di utilizzo in piena libertà è consentito nel rispetto delle regole di una convivenza civile, rispettosa e responsabile. In quanto dotati di specifiche caratteristiche fisiche, storiche, ambientali, sociali ed economiche, gli spazi pubblici rappresentano i “luoghi” della vita delle comunità e sono determinanti per il benessere individuale e sociale; sono espressione della diversità del loro comune patrimonio, culturale e naturale, e fondamento della loro identità (Convenzione Europea del Paesaggio).

Non necessariamente gli spazi pubblici sono o devono essere di proprietà pubblica, tuttavia quelli che sono anche di proprietà pubblica offrono garanzie più durature circa la loro accessibilità e fruibilità nel corso tempo, in quanto sono meno soggetti alle legittime modifiche d’uso proprie della proprietà privata.

Nello specifico è possibile distinguere tra: spazi che hanno un carattere esclusivamente o prevalentemente funzionale; spazi che presuppongono o favoriscono una fruizione di tipo individuale; e infine spazi che hanno un ruolo prevalente di fattore di aggregazione sociale, legato a particolari forme di interazione tra funzione, forma, significato, e/o al rapporto tra costruito e non-costruito.

Kalvebod Waves, Copenaghen, Danimarca. (KLAR and JDS/Julien De Dmedt Architects)

Oggi a costituire una preziosa risorsa e una grande occasione sono i “potenziali spazi pubblici” – ossia le aree di proprietà pubblica non accessibili e/o fruibili – sui quali è possibile costruire politiche integrate per il potenziamento dello spazio pubblico esistente, la riqualificazione morfologico-funzionale dei tessuti urbani e del patrimonio pubblico dismesso, la rigenerazione economica e sociale, nonché il miglioramento della qualità della vita.

Nuovi modi di ri-vendicare lo spazio pubblico

Nel corso degli ultimi decenni sono state avviate diverse politiche ed azioni finalizzate al recupero e alla riqualificazione dello spazio pubblico, a restituire alla vita sociale questi luoghi, a rendere i centri urbani più sostenibili e ad accrescere i fattori di competitività della città migliorando la sua immagine complessiva.

Il diritto ad un uso libero di spazi pubblici di qualità viene oggi fortemente rivendicato anche da numerosi movimenti e dagli stessi cittadini; la maggiore influenza della società civile nella gestione dello spazio urbano ha generato nuove modalità di approccio e strumenti innovativi di progettazione (pianificazione integrata, partecipazione pubblica, etc.) che prevedono il coinvolgimento dei cittadini. I processi di ridefinizione di tali spazi e frammenti urbani, basati da un lato sulla promozione della diversità e dall’altro sulla capacità di recupero e di innovazione, hanno la finalità di restituire un senso ai luoghi e una migliorare qualità della vita.

Zhangjiagang Town River Reconstruction, Zhangjiagang, Suzhou, Jiangsu, Cina. (Botao Landscape)

Nuovi metodi per sensibilizzare l’opinione pubblica e per la “riappropriazione” di beni comuni urbani partono dall’identificazione e dalla valorizzazione dei comportamenti collettivi, che vengono rielaborati con la finalità di incrementare le opportunità e la qualità non solo dello spazio ma anche della vita, per arrivare ad esplorare nuove modalità, creative e innovative, di immaginare la pianificazione e la gestione dello spazio pubblico. L’obiettivo è proporre strategie di progettazione inclusiva, che consentano anche l’occupazione temporale dello spazio, integrando gruppi e interessi diversi a partire dalla percezione comune dello spazio pubblico, e incoraggiando la negoziazione sociale e la partecipazione civica.

Si tratta di una grande sfida che richiede di tenere in conto delle esigenze ambientali e socio-economiche dei contesti considerati, in un confronto costante con la collettività che coinvolge in primo luogo le amministrazioni locali, nonché interessi pubblici e privati di associazioni, residenti, proprietari, investitori, etc.

Pier C Park, Hudson River Waterfront Walkway, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA. (Apollonis Wang)

La presenza dello spazio pubblico nelle città. Il ruolo della progettazione urbana

Parte integrante dell’architettura e del paesaggio urbano, patrimonio della memoria individuale e collettiva, lo spazio pubblico in quanto luogo multifunzionale ha un ruolo determinante sull’immagine complessiva della città e sulla vita quotidiana della comunità. In questo senso la progettazione dello spazio pubblico merita un’attenzione particolare.

Analizzare le condizioni complessive dei luoghi (fisiche, ambientali, climatiche, topografiche, etc) consente di riconoscere le problematiche esistenti e di valutare l’entità e il tipo di interazioni sociali tra i diversi utenti. In questo modo è possibile identificare le esigenze funzionali e le condizioni per soddisfarle, arrivando infine a definire le componenti progettuali, anche eventualmente per un uso temporaneo.

“Morske Orgulje” Sea Organ, Zara, Croazia. (Nikola Bašić)

La proposta progettuale deve essere concepita in riferimento ad un “paesaggio in interazione” destinato a differenti utenti, favorendo e facilitando le relazioni tra i soggetti e l’uso degli spazi. Questo è possibile lavorando sulle diverse scale, aprendo nuove viste e prospettive, creando porosità, rendendo efficiente e vivace il luogo, aumentando la qualità e la varietà dei servizi, migliorando l’accessibilità e l’illuminazione, etc.

Temi chiave per la progettazione sono il coinvolgimento degli stakeholder e la governance, il ruolo dello spazio pubblico in quanto “catalizzatore” delle trasformazioni socio-economiche, la selezione delle destinazioni d’uso, la creazione di luoghi inclusivi (arte, storia, patrimonio, tempo libero, etc), le scelte architettoniche e il design urbano, il miglioramento delle connessioni, l’innovazione tecnologica, le nuove forme di investimento, la sicurezza, etc.

Si tratta generalmente di progetti di medio e lungo periodo, che necessitano di tempo per garantire trasformazioni di qualità, con soluzioni sostenibili e competitive, in grado di attirare l’interesse economico e i migliori talenti provenienti da tutto il mondo, di incrementare la domanda di edilizia residenziale e il valore immobiliare, promuovendo la riqualificazione urbana delle aree adiacenti, ma allo stesso tempo con operazioni efficienti in termini di gestione.

Minghu Wetland Park, Liupanshui, Guizhou, Cina. (Turenscape)

L’acqua e lo spazio pubblico per lo sviluppo sostenibile delle comunità costiere

Le città sull’acqua possono apprezzare i vantaggi connessi con la presenza di questa preziosa risorsa e di un paesaggio dal grande fascino. In particolare, le comunità costiere possiedono un spiccato senso di luogo legato alla loro storia e alla posizione geografica. L’amore per l’elemento “acqua” è cresciuto nel corso della storia, insieme alla capacità di difendersi e di adattarsi alla sua natura; l’acqua ha lasciato il suo segno in tanti modi nei centri urbani, lungo i fiumi e i canali, nelle aree portuali, dove spesso le banchine abbandonate e in stato di degrado sono state recuperate a nuove destinazioni funzionali senza dimenticare il loro passato industriale.

Vivere sull’acqua è stato spesso conveniente, a volte pericoloso, ma sempre desiderabile, e dovrebbe rimanere tale. A stretto contatto con l’acqua, la gente del waterfront è chiamata a proteggere le risorse naturali, la storia della comunità, il patrimonio lasciato dalle attività dismesse e l’identità marittima dagli effetti della crescita urbana e degli interventi umani.

Riverside Park South Waterfront, New York, USA. (Thomas Balsley Associates)

Al giorno d’oggi rendere accessibile il fronte d’acqua delle città, realizzando nuovi spazi pubblici a servizio della comunità locale o dei visitatori, può diventare un’opportunità.

Il potenziale di investimento pubblico e privato sul waterfront appare evidente – anche rispetto alla crescita delle popolazione urbana prevista in futuro (10-20 anni, in particolare in Africa e in Asia) – come del resto negli ultimi decenni si è manifestato un forte interesse verso la riqualificazione delle aree in stato di abbandono e di degrado, che ha prodotto nel tempo interessanti risultati dal punto di vista economico, sociale ed ecologico per lo sviluppo e l’immagine delle città che si affacciano sull’acqua.

Accanto alla realizzazione di quartieri residenziali, di gallerie commerciali, di distretti d’affari, di spazi culturali, i piani per lo sviluppo e la riqualificazione dei waterfront devono necessariamente incorporare nuovi spazi pubblici e luoghi aperti, accessibili al pubblico e di qualità, integrati e connessi con il tessuto urbano mediante il trasporto pubblico (anche su acqua, a volte più efficiente e conveniente) o percorsi pedonali, sperimentando inoltre innovazioni e tecnologie avanzate.

È inoltre possibile ri-immaginare nuovi paesaggi d’acqua non solo in termini di riqualificazione urbana, di investimento economico, di rivalutazione immobiliare dei suoli, ma anche in termini di protezione e sicurezza per l’intera comunità (drenaggio, microclima, biodiversità, etc.). Gli spazi pubblici affacciati sull’acqua possono essere progettati in funzione dei cambiamenti climatici e delle calamità che gli stessi producono, in modo da garantire una maggiore resilienza urbana. Allo stesso modo in aree distrutte o fortemente compromesse da eventi catastrofici gli spazi pubblici possono avere un ruolo fondamentale per l’implementazione del processo di ricostruzione e il recupero della vita comunitaria.

Hornsbergs Strandpark, Stoccolma, Svezia. (Nyréns Arkitektkontor)

Occorre certamente un approccio equilibrato nel riconnettere la città al suo waterfront per aumentare il suo valore e le opportunità di investimento, e allo stesso tempo per realizzare un nuovo paesaggio che deve essere affascinante e fruibile al pubblico, sostenibile e resiliente.

Per garantire una crescita sostenibile e uno sviluppo intelligente, e per restituire un senso di luogo alle comunità costiere, un approccio strategico alla riqualificazione urbana del waterfront deve essere orientato a:

- ripristinare la struttura biologica e fisica del bordo d’acqua e del litorale per quanto possibile;

- migliorare l’immagine dell’interfaccia terra-acqua e del paesaggio limitrofo;

- allocare aree e spazi per programmi culturali e sociali, per attività destinate al divertimento e al tempo libero, per usi e servizi di pubblica utilità;

- ripensare processi, strumenti e metodi per ri-immaginare questi spazi urbani, le loro forme e le destinazioni d’uso in una dimensione multi-scalare che deve tener conto delle radici del contesto e delle dinamiche relazionali con il territorio

Quais Rive Gauche de la Garonne, Bordeaux, Francia. (Atelier Corajoud)

Ri-immaginare lo spazio pubblico sul waterfront

Un fronte d’acqua può assumere quindi diverse forme, è in grado di offrire e proporre differenti opportunità di fruizione, suscitare una varietà di interessi pubblici e privati, di business o ricreativi, ma un’attenzione particolare deve riguardare il contesto specifico e l’identità culturale, la capacità di sfruttare in modo intelligente, innovativo e creativo l’elemento “acqua” (e, dove presenti, altre componenti dell’ambiente naturale), valorizzando il paesaggio e mantenendo la caratteristiche distintive del luogo.

Sugar Beach, Toronto, Canada. (Claude Cormier Landscape Architects)

Tra le funzioni e gli spazi di pubblica utilità che possono essere insediate sul waterfront:

- Vie di accesso alla costa che unificano il paesaggio e costituiscono un elemento importante nel sistema di inter-connessione tra il waterfront, il tessuto urbano, le aree aperte, gli spazi pubblici e privati, etc.;

- Percorsi pedonali che attraversando gli spazi pubblici e il paesaggio naturale garantiscono l’accesso diretto all’acqua e spesso vedute straordinarie;

- Moli e banchine riqualificati, spesso destinati esclusivamente all’accesso del pubblico e a funzioni ricreative;

- Parchi naturali e aree aperte, realizzati per preservare o ripristinare l’ambiente costiero, possono accogliere diverse attività ed essere utilizzati come spazi di contemplazione e di esplorazione del paesaggio d’acqua;

- I parchi urbani che sono progettati per accogliere elementi artificiali (architetture, elementi di design, landmark, etc.) e una grande varietà di usi che consentono di apprezzare la vicinanza al waterfront;

- Aree per attività ricreative sull’acqua che consentono l’accesso fisico al waterfront per la pratica di attività e sport acquatici;

- Bacini d’acqua, utilizzati con diverse finalità (ricreative, commerciali, acquatiche, etc.), che offrono l’opportunità di apprezzare e godere il waterfront e le sue attrazioni.

Paseo Maritimio de la Playa de Poniente, Benidorm, Spagna. (OAB – Office of Architecture Barcelona, Carlos Ferrater Lambarri and Xavier Martí)

La scelta del mix funzionale, la presenza dello spazio pubblico, una programmazione flessibile in grado pertanto di adattarsi al contesto specifico e alle circostanze mutevoli, rappresentano generalmente la soluzione migliore (e auspicabile) per garantire lo sviluppo del waterfront anche in una situazione futura che può differire dallo stato attuale.

Generalmente l’accesso pubblico e la fruibilità del waterfront sono maggiormente garantiti nei casi in cui i seguenti aspetti vengono potenziali e valorizzati: continuità, mediante percorsi che connettono i bordi d’acqua, gli spazi aperti, i luoghi pubblici e le aree di attività e di servizio; sequenzialità di grandi spazi aperti da cui risulta possibile apprezzare vedute significative sull’acqua; varietà di usi e di spazi che offrono diverse opportunità per trascorre il tempo e godere del paesaggio; integrazione attraverso connessioni frequenti e comode con la città e con il territorio limitrofo; infine, ma non meno importante, specificità, ossia un carattere e un senso che le scelte architettoniche e di design urbano sono in grado di restituire al luogo sfruttando il paesaggio, la storia, il patrimonio e l’identità locale.

In questo senso, ri-immaginare il waterfront urbano risulta un processo complesso che richiede il coinvolgimento di numerosi attori, esperti nei differenti campi disciplinari (pianificatori, urbanisti e architetti, paesaggisti, sociologi, specialisti in investimenti di mercato e capitali, etc.)

North Wharf Promenade, Silo Park e Jellicoe Harbour, Auckland, New Zealand. (Taylor Cullity Lethlean & Wraight + Associates)

Determinante nel processo è il coinvolgimento dei diversi soggetti interessati, nonché la partecipazione pubblica. Sono i cittadini e gli utilizzatori a dover proporre nuovi modalità di “ri-appropriazione” del waterfront e di fruizione pubblica dello spazio affacciato sull’acqua; esigenze e desideri che altri soggetti, in funzione delle capacità e delle competenze specifiche, dovranno tradurre in una pianificazione e progettazione concreta, finalizzata alla realizzazione.

I diversi soggetti interessati per proporre una soluzione di “successo” devono coordinare i loro sforzi in un approccio integrato, che richiede una visione chiara, obiettivi condivisi, un atteggiamento flessibile, nonché la collaborazione tra enti pubblici, aziende private, esperti, consulenti, proprietari, investitori, residenti, etc.

Anchor Park, Västre Hamnen, Malmö, Svezia. (SLA, Stig L. Andersson)

Tra le finalità principali di tale approccio:

- l’apertura del waterfront al pubblico;

- una pianificazione/progettazione che dovrebbe essere aperta e partecipativa, prendere in considerazione le condizioni locali e le esigenze degli utenti finali, contribuire a re-immaginare frammenti di città;

- la realizzazione di spazi pubblici a misura d’uomo, pedonali, socievoli, vivaci e divertenti;

- la costruzione di complessi culturali, landmark urbani, spazi per socializzare e per il tempo libero, in connessione tra loro e con il territorio limitrofo;

- la creazione o valorizzazione di caratteri di contesto specifici, proponendo un’immagine originale ed esclusiva delle aree, rendendo maggiormente attraenti e confortevoli i luoghi;

- lo sviluppo di nuove attività e occupazione, di nuovi interessi e valori, in grado di attirare attirare persone creative e business;

- un paesaggio costruito che dovrebbe tutelare le risorse e il patrimonio tangile e intangile, e inoltre dovrebbe essere adattabile alle mutevoli circostanze, per evitare costosi errori che peserebbero sulle generazioni future.

Mill River Park and Greenway, Stamford, Connecticut, USA. (OLIN)

Il valore aggiunto prodotto dalla trasformazione urbana e dalla nuova accessibilità pubblica al waterfront dovrebbe portare al superamento dei conflitti e dei diversi interessi sulle aree.

Lo spazio pubblico rappresenta una risorsa e un grande potenziale per implementare processi di trasformazione in ambito urbano, in particolare in contesti caratterizzati da componenti e valori paesaggistici “forti e riconoscibili” – come l’interfaccia terra-acqua – dalla presenza di luoghi particolarmente adatti alla costruzione di polarità funzionali e di sistemi di relazione, in cui è possibile ri-immaginare nuove opportunità di sviluppo in una continuità temporale e spaziale che consente di restituire identità ai luoghi.

Head image:El Palmeral de las Sorpresas, Malaga, Spagna. (Junquera Arquitectos; Foto: Oriana Giovinazzi)