Savannah’s port is both unique and complicated in the history of port cities In the America’s. From is founding near a creek village in 1733 to the present it has remained an important location for the global economy. The history of Savannah’s river port begins with slave grown rice and cotton for the triangle trade to timber and pulp at the turn of the century. In the past decades the Port of Georgia has become a modern container port which is the only port in the United States that exports almost as much as it imports. Yet the buildings on what remains of the now endangered historic landmark river street have only survived by accident. By the early 1900s what is now river street was largely abandoned as the ports moved up and down river. Today it is a hub of tourism and hotel development. This essay reveals how while Savannah’s port infrastructure grew and continues to thrive outside the historic city, the ports earliest architectures some dating back to the early 19th century were almost entirely lost and what remains of its historic fabric, and more importantly its actual history remain fragile (previous image).

The Slave Trade and its aftermath: Building Savannah’s Port 1756-1900

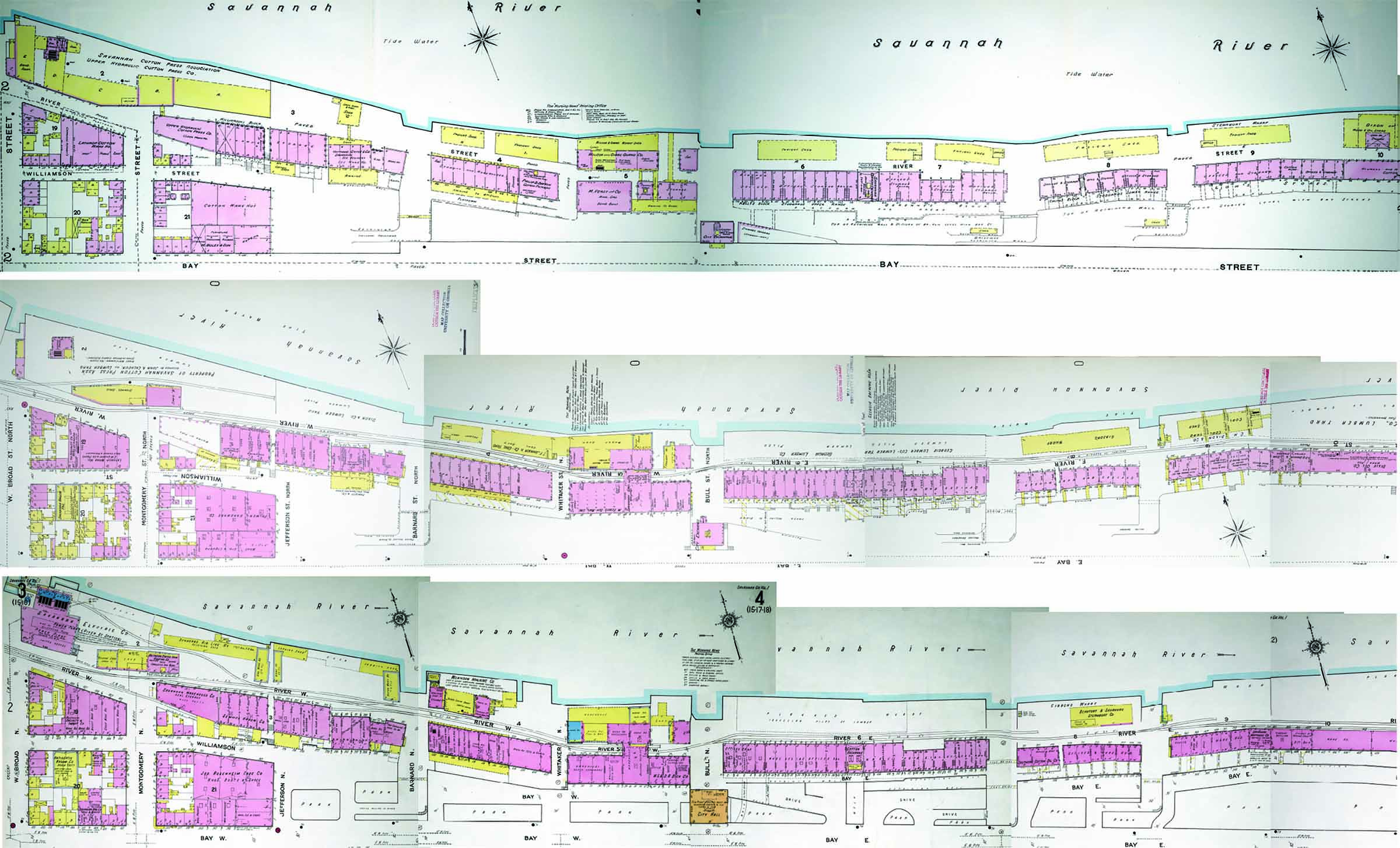

The remaining historic structures are largely downriver (east) of city hall. These were built for the slave trade. Since 17 Savannah exported slave-grown local rice and some Sea Island cotton (1992 Joyce Chaplin). The 1834 arrival of the railroad allowed what was then the capital of Georgia to export slave-grown cotton from the interior. In addition to crops, Savannah was home to the largest industrial plantation in the country. The McCalprin plantation (now demolished), with over 400 slaves, cut lumber and produced most of the bricks that built Savannah prior to the Civil War. Indeed enslaved people in Savannah built virtually all of the buildings in the city up to 1861 without compensation. Indeed following the war, their descendants continue to provide most of the construction labor. The surviving buildings from the slave trade include the 1840 the Cluskey Embankement Stores, John Stoddard’s Upper and Lower Range Warehouses, begun in 1858 along with a small handful of 1850s warehouses (next image). Later buildings include the 1876 Thomas Gamble Building, the 1886 Cotton Exchange (now Masonic Lodge), by William Preston. By 1874 exports expanded beyond cotton to include naval stores derived from the abundant southern pine forest, including pitch, resin, timber, and turpentine. By 1883 the port had expanded beyond the original waterfront to the west.

Left: View of Stoddards Range from Bay Street, Right: Cluskey Vaults facing east. (Photos by Author)

1886, 1916, 1950. Sanborn Maps. (Courtesy of the Savannah Municipal Archives)

1900-1950: Abandonment and Industrialization

By the 1920s the industrial port economy on what was once Franklin began to fail, with the exception of the new power plant built in 1911. The once prosperous river front was failing, except for timber shipping, as the steamship and export ports moved up and down river, leaving what was once Franklin street more and more abandoned. Beyond the historic port, the Savannah port economy experienced a revival due to Charles Herty 1930s research into paper and pulp waste led to the arrival of the first paper mill in 1935. More mills and industry arrived west and east of the original waterfront. The cost of this port expansion destroyed the Ancient Native American Eileen Mounds and poisoned the Savannah river and the abandonment of the original water front. Indeed, the smell of the paper mills and the pollution from our chemical factories still continues to haunt the city and the river (previous image).

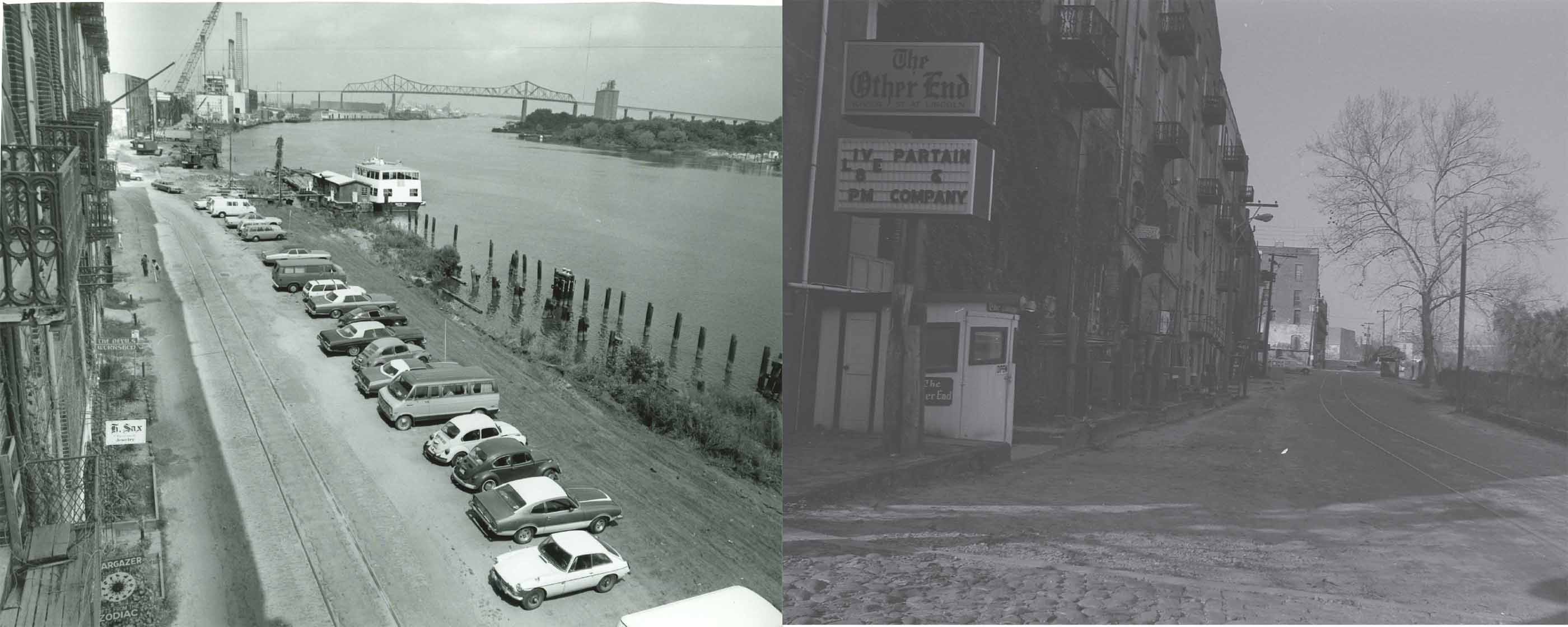

1973. Views of River Street. (Record Series 1121-056, Riverfront Urban Renewal Project designed by Gunn & Meyerhoff A.I.A., Architects Courtesy of the Municipal Archives)

By 1960s more than half the historic buildings in what is now the historic district were lost and what was once a bustling waterfront with the exception of a bar, two restaurants and a couple of business, was mostly vacant and abandoned. By the early 1970s only four shops, one bar and one restaurant remained on what was now mostly a vacant dirt parking (previous image). Indeed a developer had already demolished a large block of warehouses east of City Hall, including the 1889 Blum warehouse, (visible in the 1916 Sanborn above) which replaced the 1796 Bolton (next image). In 1969 a new Sheraton was planned for this large vacant space (now the Hyatt) to be a fifteen-story hotel and apartment complex replacing the existing warehouses. Local preservation groups and the National Trust opposed this plan. Although they were too late to stop the demolition, they succeeded in halting the construction for ten years until 1979. The developer Merrit Dixon III (who sat on the Board of the Historic Savannah Foundation) insisted that the height was necessary in order to recoup the investment given the high price of the land. Rosser Smith, Director of the Chamber of Commerce Visitor and Convention Department also defended the need for the new hotel as bringing new life to a mostly abandoned area of town. Historic Foundation Chairman of the Board, Robert Gunn, insisted that the foundation supported the new hotel as it were essential to downtown, they were just concerned about the height and the shape of the windows, which they wanted to match in shape the cotton warehouses. According to records, Ried Williamson of the Historic Savannah Foundation held up a drawing in a meeting demonstrating that a 10-story hotel with a 12-story apartment tower would only be 2-3 feet below the top of city hall. Philadelphia city planner Edmund Bacon brokered a compromise. The Hotel would be capped at the cornice of City Hall. A compromise allowed the hotel keep most of its square footage by bridging over River Street (first image).

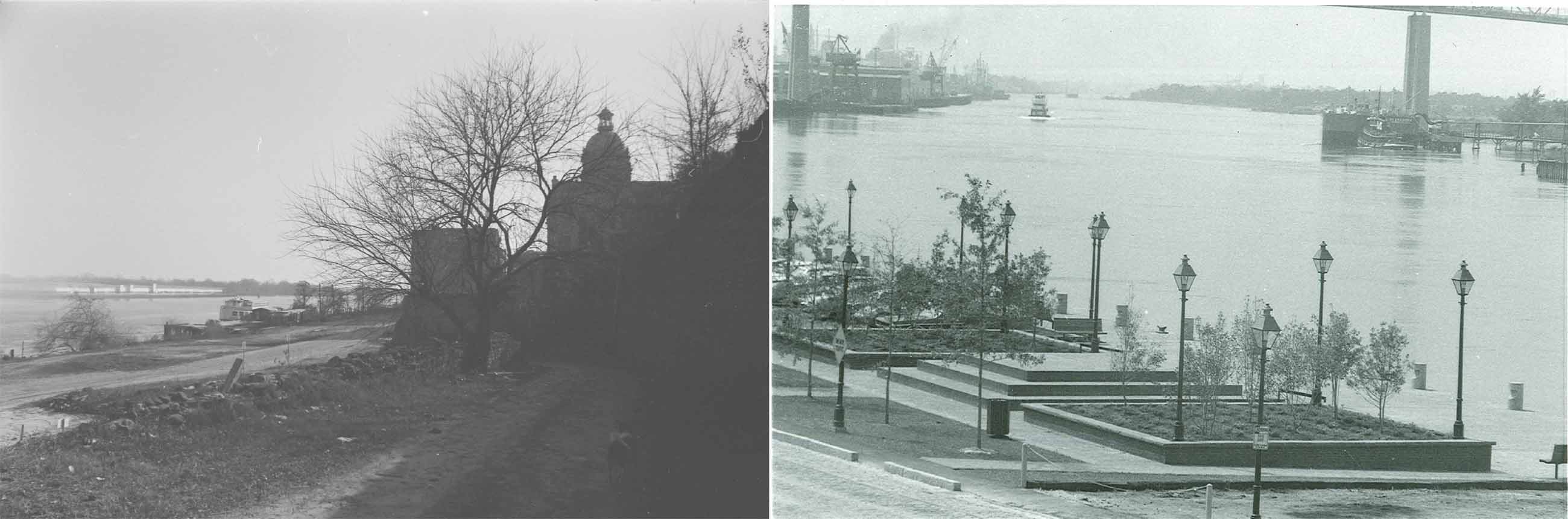

1973. Left: View of the demolition below City Hall; Right: View of the finished Rousakis looking up river. (Record Series 1121-056, Riverfront Urban Renewal Project designed by Gunn & Meyerhoff A.I.A., Architects Courtesy of the Municipal Archives).

1975 to 1990s Riverfront Revival

From 1975 to 1979 the John P. Rousakis Riverfront plan took the long-abandoned riverfront began to remake it into what is today. Mayor Rousakis, who presided over some of the worst demolitions in the city extended the new riverfront almost 20 feet. The Urban Renewal of River Street Project turned the riverfront from abandoned dirt wasteland with empty old warehouses into developed walkways and newly designed planters and low sitting walls inspired by the squares. Savannah used Federal grants of $7.3 million dollars including funds from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Community Development Block Grants and the Environmental Protection Agency, along with city money. Retired architect Eric Meyerhoff and his partner Robert Gunn worked with the city while Sarah Ward, the preservation planner for the Chatham-Savannah Metropolitan Planning Commission had the difficult task of negotiating the plan with the many conflicting constituencies.

However, the early 1980s businesses began to return to the newly remodeled River Street despite the violent reputation of the city during this decade. Tourism began to spike in the early 1990s due to a number of events helped to revitalize the Historic District and the Riverfront. The Savannah College of Art and Design, founded in 1979 purchased and adapted a several abandoned buildings in the Historic Landmark District, bringing much needed life and income to the city by 1990. Then Hollywood came to the rescue. Forrest Gump in 1999 and the publication and subsequent film Midnight of Garden Good and Evil brought the first waves of tourists to the city.

River Street: Hotels, Tourism and the Fragile Future

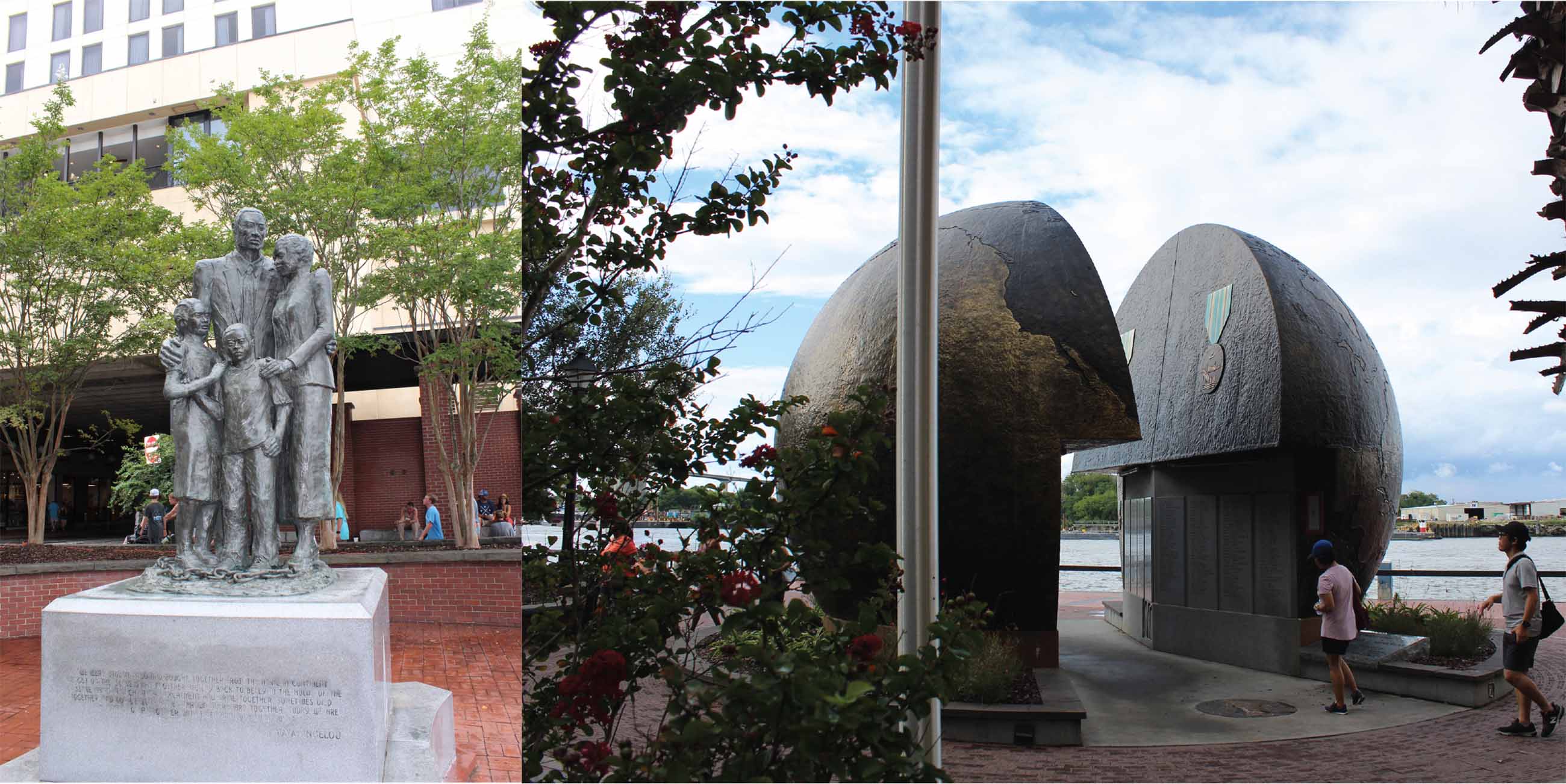

Left: Monument to Slavery below City Hall; Right: World War II Monument on East River Street. (Photos by Author)

In 2002, after a ten-year struggle, Dorothy Spradley’s monument to African American Slaves went up below City Hall arguably the first marker to publicly acknowledge the river’s slave-based history. Indeed, despite its massive history of slavery, the city and its residents have resisted any overt acknowledgement of its past until. Municipal archivist, Luciana Spracher discovered that Savannah played an enormous role in the war, building the wooden Liberty landing craft and playing host to the fleet that briefly occupied the abandoned wharfs. Therefore, Spradley’s monument, was followed by Eric Meyerhoff’s monument to World War II split into the two areas of the war with the names of local soldiers who died in the middle (next image).

View of the new Power plant Hotel under Construction on River Street East. (Photo by Author)

In 2009 the new Bohemian hotel by the developer Richard Kessler replaced an older structure next to the Hyatt, as the city continued to encourage hotel development over historic fabric. In 2018 the City was warned by the National Park Service that it may lose its Historic Landmark designation, moving its rating from satisfactory to threatened. The city does not have an archaeological ordinance, allowing new development to excavate the past and dump it down river. What is more the city often subsidize hotel development with debt and tax exemptions within the historic district, in a desperate scramble for the tourist and non-resident tax income. Even Bay Street just above River Street has few historic buildings. Most have been replaced by hotels in a vaguely historicist style of brick cladding (third image). The largest new project by Richard Kessler on River street now known as the Plant Riverside. This 80,000 square foot-project demonstrates not only the subsidized addiction to hotel development for one of the most powerful developers in the south, but also the careless use of style to mask the loss of history (next image).

Left: Aerial View of Port; Right: Ship leaving port. (Photo By Author)

Conclusion: The Port of Georgia in the Present

In 1991 the controversially named new Talmadge bridge allowed larger ships to what will become a new container port. New cranes continued to arrive from the 1990s through 2018 Today Port of Georgia is unique in the United States as it is the only port that exports almost as much as it imports. Despite the long and narrow path from the sea, the port is the western-most port on the Atlantic Coast. This allows goods to stay in the water longer. What is more, the rising Asian economy uses the port, which exports chicken parts, Kaolin clay (used for publication), pulp and paper in massive quantities. The Port employs more people in the region than tourism and facilitates the growing manufacturing centers around Savannah including Gulfstream, JCB, International Paper, Koch Industries’ Georgia-Pacific, and European chemical giant BASF. The Port is connected to a global network of commercial production, as well as to a transportation system that connects industrial and commercial goods to most consumers through the intermodal hubs that move through Atlanta. However, the Port of Georgia, which dominates the river up and downstream from the historic district and supplies one in twelve of the jobs in the state is in danger of losing its power to export to Asia due the current Administration’s trade wars. Indeed, as mentioned despite the complete restaurant and tourist revitalization of the river front, the Savannah River itself is still one of the most toxic rivers in the country, as the State of Georgia allows the paper mills, chemical factories, and treatment plants to self-regulate. Indeed, many of the industrial sites along the river are exempt from the Clean Water Act, which are being weakened by the current administration (previous image).

Acknowledge

Special thanks to Lucaina Spracher for access to the Municipal Archives for images and documentation on the history of River Street.

References

Curl, Eric. “National Park Service Determines Savannah Historic District ‘Threatened.’” Savannah Morning News. Accessed September 13, 2019.

Germaine M. Reed, “Realization of a Dream: Charles H. Herty and the South’s First Newsprint Mill.” Forest & Conservation History 39, no. 1 (1995): 4-16.

Newkirk, Margaret, and James Nash. “Savannah Surges as Major Port for Imports on U.S. Growth.” Bloomberg, October 28, 2014.

“Report Calls Savannah River Third Most Toxic in America – News – Savannah Morning News – Savannah, GA.” Savannah Morning News (June 2014)

Robin Williams, ed. Buildings of Savannah, Society of Architectural Historians: Buildings of the United States Series (University of Virginia Press, 2016).

Head image: View of River Street to the Hyatt. (Photo by Author)