It is the river and the sea that have shaped the settlement of Sheerness, a small port town located at the intersection of the river Medway with the Thames estuary on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in Kent, England. With a population of 12.000 it is the largest town on the island. Along the river, the town prospered gaining a key role in ship building and repair, in national defence of the coast and support for the Royal Navy.

Sheerness Royal Naval Dockyard was laid out by Samuel Pepsy, Clerk of the Acts[1] of the Navy Board, in 1665, initially for cleaning and repair of the smaller ships of the North Sea fleet, thus avoiding taking them up to Chatham dockyard, situated further into the bank of river Medway (Fellows 1974, 6).

Today, the present town includes the modern commercial Port that occupies the bank of the Medway River to the east and three main areas: Blue Town in the centre, corresponding with the original settlement, is surrounded by trading estates, industrial complexes and the docks; Mile Town to the east, featuring a commercial and shopping centre focused on the High Street and a seaside resort; and Marine Town which lies further to the east along the beach (next image).

The three areas had already established by the mid-nineteenth century and amalgamated during the 19th and 20th centuries, but regrettably, many 18th century timber houses and alleys have been demolished in the early 1950s whilst the steelworks were established on part of the site in 1972 clearing tracks of the former layout (English Heritage 2004, 7).

Nonetheless, the dockyard presents the largest concentration of listed[2] buildings of the region including the earliest surviving multi-storey iron-framed and panel-structured building in the World, the Boat Store built in 1859 and designed by Godfrey Thomas Greene, the many naval buildings designed by John Rennie and the Dockyard Church designed by George Ledwell Taylor (Swale Borough Council 2017, 4).

Map of Sheerness showing plan components. (Source: Elaboration by the author on Google Maps)

Rise and fall of Sheerness Royal Dockyard

At the time of the French wars of 1539-1547, a blockhouse fort was built in 1545 at Garrison Point on the north-west promontory of Sheerness (Gulvin 1975, 24-25), to protect the mouth of the Medway River and the already established Royal Dockyard of Chatham.

During the first year of the Second Dutch War in 1665, the Navy Board ordered Chatham to equip Sheerness with a facility for cleaning and repairing warships and to supply a workforce. However, when in 1667 the Dutch Fleet attacked the area, Sheerness fort offered little resistance and it was seized and burnt alongside with the dockyard. Subsequently, reconstruction works began on rebuilding both and between 1680 and 1692 barrack-like accommodations and a market were built for the shipbuilders and artificers (English Heritage 2004, 2).

During the first half of the 18th century, the dockyard grew steadily by means of a land reclamation system and, as a second dry dock was built in 1720, it became a proper ship construction yard, mainly for fourth -and fifth- rate ships.

Further defences were provided and improved in the late eighteenth century with the Inner Lines that included Musketry Wall, Fort Townsend and the Ravelin added in 1816 (Harris 1984, 266). With the construction of Queenborough Lines in 1862 and Barton’s Point Battery in 1890 the settlement was confined within the defence lines and by the 20th century all the areas had merged in one large urban sprawl (English Heritage 2004, 8).

Despite the fortifications, of all the Royal Naval Dockyards, Sheerness was the most vulnerable due to its exposed promontory and marshland. The unhealthy conditions discouraged workers from living in the area even though some housing were built around the early 18th century. By 1808 the town consisted of two dry docks and slips and around thirty buildings and yet the dockyard struggled to keep up with the work expected, as there was a shortage of housing and the buildings were badly placed. These poor conditions were reported (Harris 1984, 267) and between 1813 and 1830 a comprehensive redevelopment of the Royal Naval Dockyard was engineered by John Rennie, who designed a completely new dockyard and reclaimed the land by driving in timber piles into the marshy coastal ground. To illustrate Rennie’s design a large wooden model was built that showed each building meticulously in details[3]. The new dockyard, largely built in granite, had five bay docks with basins, and were provided with machine shops and a large storehouse, all contained within stonewalls, with large cast-iron gates (English Heritage 2004, 3). The redevelopment encompassed new residences for military officers and workers including the Captain Superintendent House, the Admiralty House and the Naval Terrace in 1827 to supplement the provision of housing in Blue Town and Mile Town (next image).

The Naval Terrace and the Dockyard Church. (Source: © Giovanna Piga)

Blue Town

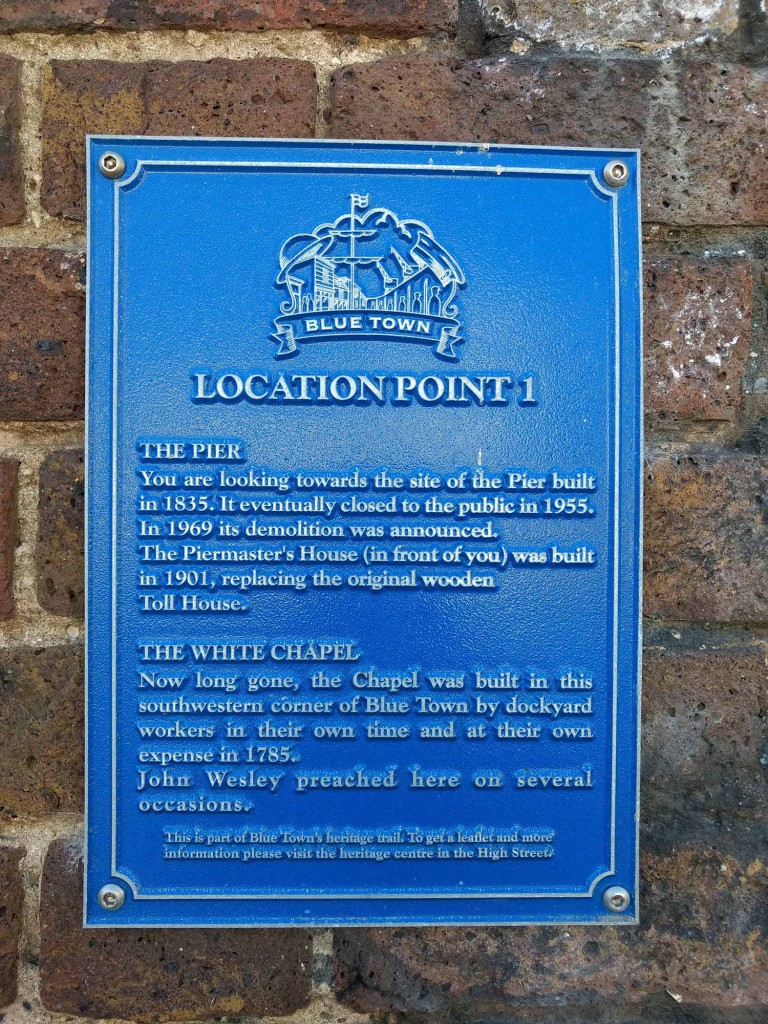

The establishment of private housing close to the dockyard started after 1738 to provide accommodation to the workforce who had been housed until then at the fort or in old hulks (Swale Borough Council 2011, 16). They were probably constructed with timber taken from the dockyard as the labourers’ perquisites. They were all painted in dark grey-blue dockyard paint, hence the name ‘The Blew Houses’, and Blue Town (Harris, 1984, 261). As Blue Town grew rapidly and the population expanded, the authorities provided new barrack-like accommodation, the ‘Great Alleys’ inside the fort which remained in use until 1820 when large numbers of workers rented cheaper accommodations in Blue Town or in the new settlement of Mile Town (English Heritage 2004, 3). Blue Town continued to expand fully occupying the triangular area adjacent to the fort. When John Rennie began to construct the new dockyard in 1813, he proposed to demolish Blue Town houses, and to use the land for the dockyard expansion. Although the plan was not entirely fulfilled, some temporary housing and dwellings were demolished in 1818, exacerbating the acute housing shortage, which was even worsen up by a fire that in 1827 and 1839 destroyed most of the timber houses in Blue Town, finally leading to the reconstruction and the development of Mile Town. The pier (now demolished) was erected in 1835 to the south of the dockyard (next image).

Mile Town

From the early 18th century, there was a small settlement at ‘Mile Houses’ that only began to grow after Rennie’s plan when the Blue Town Houses were demolished and their inhabitants moved in. The trail linking Mile Houses with the dockyard became the High Street of Mile Town and other houses were added to the south. Part of the town became known as Bank Town named after the land owner sir Edward Bank who endeavoured to develop Sheerness as a seaside town by restoring the pier and establishing a boat service from London. From the 1820s onward, Mile Town grew steadily westwards encroaching on the fortification lines, when in 1827 the government purchased land to create a buffer zone and limit further expansion.

Marine Town

Developed to the north-east of Mile Town until 1862, when the dockyard fortifications were further expanded by building the Queenborough Lines, a massive bastion and ditch running from the coast east of Marine Town to the river Medway. Blue Town, Mile Town and Marine Town were all contained within the triangular area bordered by the Queenborough Lines, and they amalgamated to form the present Sheerness (English Heritage 2004, 4).

The plaque indicating the site of the pier. (Source: © Giovanna Piga)

By the 1860s Sheerness had a growing population and was well provided with a railway, a pier and a promenade, a boat service, retail premises, shops and craftsmen, a church an open-air swimming pool and bathing machines on the beach, two newspapers, numerous pubs and several hotels, barracks and a flourishing dockyard, whilst a bank was opened by the London County Bank in Blue Town. A theatre opened in 1803 just outside the dockyard, which went lost after the Rennie’s plan, but another theatre, The Criterion Music Hall was opened by the mid-nineteenth century, and in 1851 the Hippodrome Theatre was built.

Therefore, the major urban characteristics of present-day Sheerness were established and the dockyard continued to be the main source of employment in town until the early 1960s, when, following the end of the World War II, the permanent coastal fortifications became gradually obsolete, the defensive installations of Sheerness were wound down, the associated land and buildings disposed of and Sheerness Dockyard was formally closed and taken over by a private company. Initially known as Sheerness Port Infrastructure (Conway, M. and Averby, K. 2016, 22) the company took advantage of the existing commercial dockyard that provided sufficient working space and well-developed naval infrastructures to establish a commercial port specialised in the automotive import and export. Additional space was required and created through extensive land reclamation programme from the river Medway, known as the Lappel Reclamation (Peel Ports 2014).

The continued updating of the waterfront and associated infrastructure, as well as the development of new housing, industrial estates, residential facilities and schools demonstrate the importance of the seaside economy to Sheerness. The establishment of the commercial port brought extensive changes and loss of many of the historic buildings of the town.

Today, the economy of Sheerness is still largely relaying on port activities and the development and maintenance of an attractive waterfront would put the town in competition with the other seaside centres in the region.

To this end, the acknowledgment of the historic heritage associated with the many phases of activities of the dockyards and the fortification of the area, combined with an understanding of the drivers of changes that shaped Sheerness’ development in the past are essential to gain a deeper insight into its present character and to foresee future opportunities for its renewal.

Towards Heritage-led Regeneration in Sheerness

In 2010, Sheerness Royal Naval Dockyard, nominated by SAVE Britain’s Heritage[4], has been included on the World Monument Watch[5] list. In 1972 Swale Borough Council designated Sheerness Dockyard as a Conservation Area [6] and in 1976 also Mile Town and Marine town were included (Swale Borough Council 2011, 4) to protect historic heritage from destruction. The Conservation Area can be divided into three character areas: the Sheerness Defences, the Royal Dockyard and Blue Town.

The relationship of the former dockyard and Blue town with the water is crucial to the Conservation Area and defines its setting.

The 60-acre site of the Royal Naval Dockyard included an impressive range of historic buildings and structures which passed to a commercial port company when the dockyard was closed in the 1960s. It was very little known and valued when, over the course of the couple of decades, more than fifty structures were demolished. Nonetheless, many survived and together with the distinctive grid of small streets and alleyways of Blue Town are now in urgent need of repair, maintenance and appropriate re-use as the whole site has huge potential to become a heritage hub, a tourist attraction and a residential quarter.

The appreciation of the distinctive character of historic buildings and sites, many of them presently under-recognised and neglected, should underpin both conservation and regeneration decisions in Sheerness. The presentation and on-site interpretation of the historic heritage will help the community draw the most from Sheerness’s rich and varied history. Reuse of landmark buildings such as the Dockyard Church, the Boat Store, the Mast House, and the renewal of the historic quarter and open spaces, would provide focal points common to both existing and new communities, and engender and sustain a sense of place.

Heritage-led regeneration is key for sustaining and enhancing the significance of heritage assets and acting as a catalyst for change.

The Sheerness Dockyard historic quarter comprises the most important part of J. Rennie’s original plan and its heritage and cultural significance is now widely recognised and accepted as being of international importance.

Key historic areas within the former dockyard and a substantial number of historic buildings were vacant and neglected, as several reports and surveys conducted by local authorities and trusts documented[7], when around year 2000 the historic quarter was sold to a developer who planned to transform it into a residential estate by building over the historic landscape. When the plan failed to get planning permission, and following a hard-fought campaign supported by English Heritage, the World Monument Fund and SAVE Britain’s Heritage, the historic quarter was acquired by the local authority and passed on to the Spitalfields Historic Buildings Trust[8] in March 2011 which, via a new company, the Sheerness Dockyard Preservation Trust, funded by a group of owner/investors and loan from the Architectural Heritage Fund, took on six Grade II* and four Grade II late-Georgian listed buildings which were included within the residential quarter of the walled Royal Naval Dockyard (Swale Borough Council 2011, 51).

Since then many buildings and the surrounding landscape have undergone an extensive restoration programme.

The Dockyard Wall separating Blue Town from the former Royal Naval Dockyard area and the Port with the Naval terrace in the background. (Source: © Giovanna Piga)

In 2013 the Trust took on ownership of the derelict Dockyard Church (next image), a fine Grade II*-listed church, which stands just outside the dockyard wall (previous image). The church has an austere neo-classical design with a tetrastyle Ionic portico. It was gutted by fire in 1881 and substantially rebuilt within the masonry envelope, close to the original concept, in 1884-5. The church continued to be in use for a time after the closure of the Naval Dockyard in 1960 before becoming a sports facility and later a store and was devastated again by a fire in 2001. Sheerness Dockyard Preservation Trust sees through the project of repairing the building and converting it to a mixed-use space featuring a permanent gallery to display the famous 160m2 model of the dockyard constructed when it was first laid out. The restoration of the church is an ongoing project and the acquisition of the residential quarter at Sheerness is rightly hailed as one of the great heritage rescues of the early 21st century.

It has been seen elsewhere in the Thames Gateway Kent[9] that investment in historic assets directly contributes to the wider socio-economic objectives of regeneration (Bee, S., Douglas, L. and McCallum, D. 2005) and that in ‘growing spaces’ like Sheerness, the distinctive historic features could be used as catalysts for conservation-led regeneration (Conway, M. and Averby, K. 2016). As such, heritage-led regeneration is a key issue for the port of Sheerness as a whole.

The Dockyard Church: the tetrastyle Ionic portico and the back. (Source: © Miki Fossati).

The port of Sheerness has always played an important role in the economy of the Isle of Sheppey and is now classified by the Department for Transport as a ‘major’ port for its good infrastructures, including access to the wider road and rail networks; covering more than 1.5 million m2, is one of the largest foreign car importer in the UK. This importance will be further prompted by the considerable changes that the town will see over the coming decades: the whole area of the dockyards including the port of Sheerness, is now part of the Peel Port Group, one of the largest port operators in the UK, that has produced a masterplan plan for the regeneration of these areas[10]. Sheerness Port Master Plan (Peel Port 2014) is now being finalised, following consultations with residents and stakeholders on the 2014 draft masterplan, which illustrated a strategy for the sustainable expansion of the port including improvement for transportation and access as well as the socio-economic benefits that it was likely to generate for the region.

The masterplan highlighted five major areas of intervention of which the most relevant to the present article’s focus are: Option for change 2: Heritage Quarter and Option for change 3: Steelwork Site.

What is indicated as Heritage Quarter corresponds to the former Royal Naval Dockyards area where there are seventeen listed buildings alongside with a Scheduled Ancient Monument and a designated Conservation Area (next image).

The proposal opts to open up this area of the Port by removing it from the port boundary and relocating the current entrance to the Port to allow for public access to the heritage quarter. The ideal development of the area will be for mixed-use purposes including office, retail, residential, and leisure spaces, ensuring that the listed buildings are converted into beneficial occupation and re-use and thereby contributing to their ongoing maintenance.

The many port warehouses in this area will be removed whilst new residential infill development promoted to boost the regeneration and ensure the creation of an attractive heritage quarter.

The various options for the re-use and redevelopment of the whole area will be explored in conjunction with Swale Council and English Heritage.

Adjacent the current port operational area is the site of the former Steelworks, which is also in need of regeneration. The site could provide operational land for the ports activities, while contributing to the improvement of the residential areas which were negatively impacted by the previous steelworks’ activities.

However, the Steelworks Site’s ownership is not the Port of Sheerness, and should the opportunity arose for it to became so, the Port of Sheerness would wish to bring the entirety or part of the site into port use.

Sheerness Dockyard Historic Quarter and Conservation Area. (Source: Elaboration by the author on Google Maps).

Access to the site would be via a new road bridge linking the existing Port with the steelworks so as to allow for direct access to the site.

Given the scale of the site and its convenient access to the rail network, if port activities will be extended onto the site, the Council will expect proposals for the use of existing rail infrastructure.

Priority will be to safeguard the port function and to maintain and enhance the role of the Port of Sheerness as a deep-water gateway port to Europe. Future expansion could potentially involve intensification of port use both within the existing confines and via expansion onto appropriate nearby land or through land reclamation. In the longer term, the regeneration of the Port of Sheerness could play a significant role in the wider regeneration of the Borough as it represents a major opportunity for the communities on western Sheppey, which are currently experiencing high levels of social and economic deprivation.

Conclusions

Sheerness historic urban landscape managed to survive decades of abandonment and negligence and is now at the mercy of drivers of change that are relying on a heritage-led regeneration to prompt future opportunities of renewal.

The town has lost the distinctive naval and dockyard base role that has characterised it for centuries and is consolidating a socio-economic alternative that will position it among the gateway ports in Europe.

The regeneration is far from being accomplished and whilst some buildings are under renovation works, many are threatened by disregard and are rapidly deteriorating (this is the case for example of the Boat Store and Mast House) and a lot has been lost of the large historic heritage.

Sheerness is likely to see significant changes in the years to come and the conservation and appropriate re-use of the remarkable heritage assets of the Sheerness Defences, the Royal Dockyard and Blue Town will play a significant role in driving the heritage-led regeneration.

Moreover, Sheerness is an archetypical example of a contemporary waterfront town with an operational commercial port, seafront and significant historic heritage that is manifested not only in the remains of the old buildings and structures but even more in the grid plan of the streets, lanes and alleyways, resulting from the continued updating of its layout and re-use of the infrastructures to adapt to the changed conditions. The successful heritage-led regeneration process will take account of this unique character to restore a sense of place and identity for the community.

Notes

[1] A civilian officer of the Royal Navy originally known as Keeper of the King’s Ports and Galleys.

[2] A listed building is included in one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England, Historic Environment in Scotland, Cadw in Wales, and Northern Ireland Environment Agency. There are three types of listed status Grade I: buildings of exceptional interest; Grade II*: particularly important buildings of more than special interest; Grade II: buildings that are of special interest, warranting every effort to preserve them.

[3] The model covers 160 m2 and survives intact in the custody of the English Heritage, waiting to find its new home once the Dockyard Church restoration will be completed.

[4] SAVE Britain’s Heritage is an independent group of architectural historians, journalists and planners that has been campaigning for the conservation of threatened historic buildings and sustainable reuses since 1975.

[5] The World Monuments Watch is a global programme that aims to identify imperiled cultural heritage sites and direct financial and technical support for their preservation. It was launched in 1995 on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of World Monuments Fund, a private non-profit organization founded in 1965 by individuals concerned about the accelerating destruction of important artistic treasures throughout the world.

[6] Conservation Areas were first introduced in the Civic Amenities Act of 1967 and define an area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance (s.69 Planning – Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas – Act 1990).

[7] For example: Swale Borough Council (2011), Swale Borough Council (2017), English Heritage (2004).

[8] Spitalfields Historic Buildings Trust set up as a UK Charity in 1977, saves and repairs buildings that are at risk of demolition.

[9] Thames Gateway Kent covers broadly the area east of the M25, bounded to the north by the Thames River and Estuary and to the south by the A2 and the North Downs.

[10] The Master Plan was formulated in accordance with guidelines laid out by the ‘Guidance on the preparation of the Port Master Plans’ published by the UK Department of Transport (DfT) in 2008.

References

Barson, S. et al. (2006). Queenborough, isle of Sheppey, Kent. Historic area appraisal. Swindon: English Heritage Press.

Bee, S., Douglas, L. and McCallum, D. (2005). Growing places: heritage and a sustainable future for the Thames Gateway. London: English Heritage Press.

Conway, M. and Averby, K. (2016). A characterisation of Sheerness, Kent. Project Report 61034355. London: Historic England.

DoE (1978). List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest. Queenborough in Sheppey.

English Heritage (2004). Kent Historic Towns Survey. Sheerness Archaeological Assessment Document. London: English Heritage Press.

Fellows, J. (1974). Shipbuilding at Sheerness: The Period 1750–1802. The Mariner’s Mirror, 60:1, 73-83.

Gulvin, K.R. (1975). The Medway Forts, a Short Guide. Medway: Military Research Group.

Harris, T.M. (1984). Government and urban Development in Kent: The case of the Royal Naval Dockyard Town of Sheerness. Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol. 101, 245-276.

Hughes, D. T. (2003). Sheerness Naval Dockyard & Garrison. Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing Limited.

Peel Ports (2014). Sheerness Port Master Plan: A 20 year Strategy for Growth – Consultation Draft. Liverpool: Peel Ports Group.

Swale Borough Council (2011). Sheerness: Royal Naval Dockyard and Bluetown Conservation Area. Character Appraisal and Management Strategy. Sittingbourne: Swale Borough Council.

Swale Borough Council (2017). The Built environment. Topic paper 4. Sittingbourne: Swale Borough Council.

Websites

https://www.kentonline.co.uk/sheerness/news/urgent-call-to-save-kents-naval-heritage-201278/

https://navaldockyards.org/sheerness/

https://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/researchers/research-guides/research-guide-b5-royal-naval-dockyards

https://www.seh.co.uk/projects/sheerness-dockyard-church/

https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/a-short-history-of-sheerness-dockyard/

http://www.thespitalfieldstrust.com/project/sheerness-dockyard-church/

https://wmf.org.uk/Projects/sheerness-dockyard/

Head Image: Aerial photo of the Port of Sheerness.